Treatment GuideJust DiagnosedSex & DatingAfrican AmericanStigmaAsk the HIV DocPrEP En EspañolNewsVoicesPrint IssueVideoOut 100

CONTACTCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2024 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

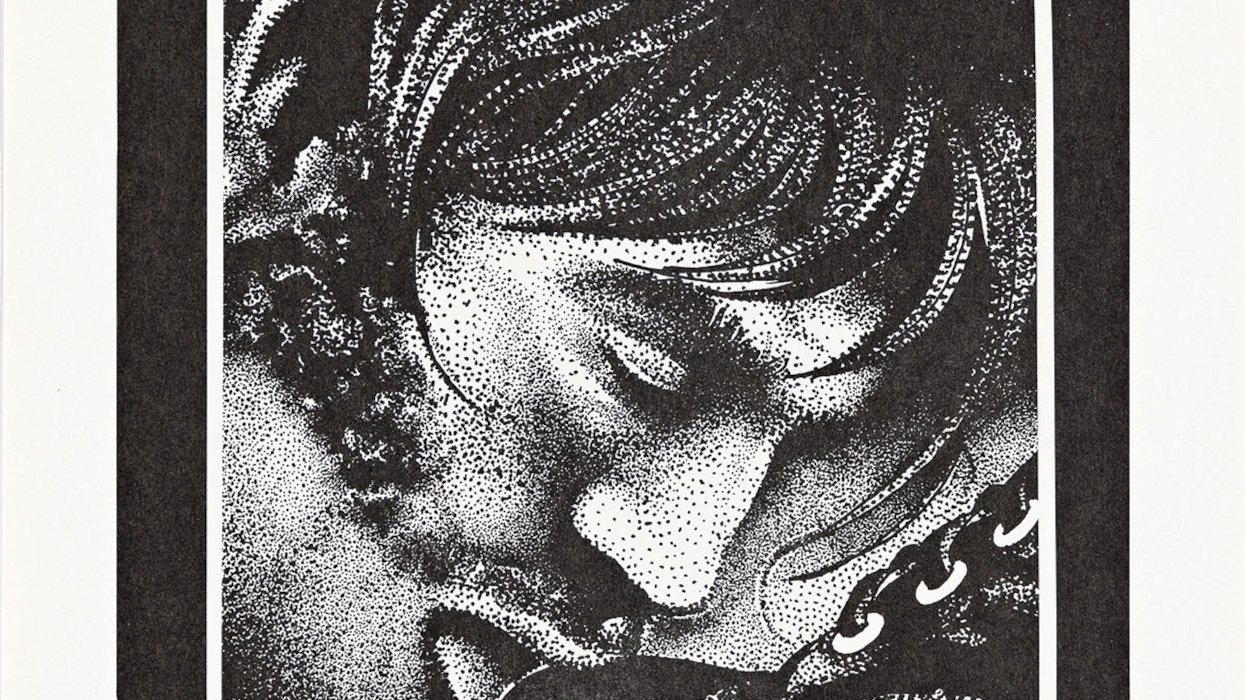

Tim'm West stands before an enthusiastic crowd and smiles at the response to his song about greed in the hip-hop industry.

But the 36-year-old musician, poet, songwriter, and scholar is preparing to continue his set by taking his audience on an unexpected journey'deep into his personal experiences as a black gay man living with AIDS. And while he's not sure how well this change in direction will be received, it's a path he feels that he and his listeners must go down.

'I've gotta tell you what's up. I'm gonna keep my head up. Now, I can mope about it, or I can do something about it. I can give all I got to give. Do what I need to do to live. Keep it positive,' West sings as he launches into his song 'Positive.'

'Creating and performing music for me is therapeutic'it's medicine,' says West, who is also a lecturer at California's Humboldt State University. 'People who are HIV-positive have a lot of burnout. For me, music is one of the ways to escape that. It brings me a lot of peace and calm.'

West is experiencing what doctors and therapists call the healing power of music. According to psychologists, writing, recording, and performing music'or even simply listening or singing along'can convey powerful emotional and physical health benefits.

'Just think about how you already use music to better your life,' says Michelle Reitman, a psychologist and board-certified music therapist at Cadenza Music Therapy in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. 'We listen to it to pass time in a waiting room. We use it when we're in stressful, hair-pulling traffic to relax. We play it to get ourselves revved up before a night out. That's because studies have shown music actually changes levels of endorphins,' feel-good brain chemicals that have mood-improving effects similar to those of some opiate drugs.

Studies have also shown that immersing oneself in music can boost immune-system function and ease adverse medication side effects, notes Shara Sand, a New York City psychologist who's worked with HIV patients since 1990. 'The physical effects,' she says, 'are quite profound.'

Chuck Panozzo, bassist with the rock band Styx, is a firm believer in the health benefits of music. He credits performing'and, while he was very sick, just the hopeful plan of eventually returning to touring'with helping him rebound from serious AIDS-related complications in the early 1990s.

'I've been a musician since I was 7. It's just a part of me,' Panozzo says. 'I believe it was literally hurting my health not to be up onstage performing. So I set a goal to 'come back,' to be back onstage and be a viable, contributing member of the band. I had to. The energy, the unconditional love, the support I get when I'm playing'it makes me whole.'

Panozzo staged his comeback in September 1999 in Las Vegas, where he was greeted with a raucous standing ovation. 'The fact that I was able to go back to my 'job' was a vital part of me getting healthy again,' he says. 'And that ovation I got was as powerful as any of the meds I was taking.'

Today, the 60-year-old has an undetectable viral load and a high, stable CD4-cell count, and he is still traveling with Styx as the band performs regularly around the country.

Rickey Payton Sr. readies himself for a daunting task: Teaching 10 teenagers how to write, arrange, and perform their own songs at Camp Hollywood Heart, a weeklong summer camp in Malibu, Calif., for kids affected by HIV.

The respected Washington, D.C.'based musician, music producer, and cofounder of the organization Urban Nation Inc., was back for his third stint at the camp despite his wedding being just one week away. His bride-to-be also had insisted that he go in memory of his brother who died of AIDS complications in 1996.

I have to be there, Payton told himself. These young people all have something to say. I need to help give them a platform to do that. I need to help empower them.

A handful of AIDS, youth, and arts groups around the country'like Camp Hollywood Heart'have recognized the health benefits of music and are using it as a therapeutic tool. The results, counselors say, are tangible and potent, particularly among young HIVers.

'There was one girl who was really withdrawn,' Payton says of the 2008 summer camp. 'And she really didn't like talking about HIV. But she ended up performing a very personal song written by the young people in camp about living with HIV, and she couldn't have been prouder or more animated when she performed for the whole camp. That's powerful. Helping these young people express something they normally would keep deep inside them is' There aren't words for it.'

At AIDS Foundation Houston's annual Teen Leadership Forum, young people with HIV spend a week living on a college campus in Texas, talking and learning about issues like how to handle dating and relationship challenges, setting personal and professional goals, and examining possible career choices, including jobs in the music industry.

Musician, music video producer, and DJ Kirby Gray'better known by the moniker DJ Grayface'gave the kids at this past year's forum a crash course in music production, including writing and recording their own hip-hop songs.

For many of the participants, the resulting musical pieces were enormously cathartic, says Kelly McCann, the foundation's chief executive officer. 'The emotions just flow out of these young people in a way that never would if they were to give a talk or write an essay,' she marvels.

That ability to express deeply held, even suppressed emotions produces extraordinary mental and physical health benefits, says Charles Konia, an Easton, Pa.'based psychiatrist. 'It's freeing; it provides an enormous sense of release,' he says. 'With that relief comes lowered levels of anxiety and stress, both of which can have serious health repercussions if left unchecked.'

'Kids don't want lectures about HIV; that's kryptonite to them,' DJ Grayface says to himself as he prepares to perform at AIDS Foundation Houston's Teen Leadership Forum. 'Telling them not to have sex or to use condoms is like telling them to go study. Nobody responds to that.'

'But these kids learned rap songs before they learned their multiplication tables,' he notes. 'If I can couch HIV prevention information in a song with a good beat, it will connect with them. I can connect with them.'

Musicians like Gray and West are well aware that the role of music in the fight against HIV isn't limited to people personally affected by the disease. It's also a wide-reaching but mostly untapped medium to educate the masses about the virus and how to prevent spreading it.

To Gray, his educational form of hip-hop music also offers what he believes is a much-needed counterbalance to popular music that he says fuels the HIV epidemic among young people.

'The music out there tells young people to have sex, sex, sex, and more sex,' Gray says. West agrees: 'You've got hip-hop artists appearing in public service announcements saying 'use condoms,' then going out on stage singing about 'hitting it raw.' Which of those messages do you think sticks?'

Gray says he's fighting back with 'positive' hip-hop songs. 'I take the same energy and beat a street rapper or gangsta rapper would use, but I use it to encourage behavior change and empower listeners,' he explains. 'It's kind of like tricking kids into eating their vegetables. You have to camouflage it and mix with something they will accept.'

West focuses his musical education efforts more toward adults, particularly African-Americans, among whom, he says, HIV and homosexuality are still largely taboo topics. And because of this, he says, his eye-opening lyrics about these topics aren't always warmly embraced.

'I did an open mike in Houston, and my second song was essentially my HIV coming-out story,' he explains. 'It wasn't received terribly well. There was nothing mean or overt, but I could tell people were uncomfortable with the topic and with me'as a black gay man'challenging the black community on its homophobia.'

But whether listeners are comfortable or not, West says, they do hear the message loud and clear.

'They may not come up to me and talk with me after my show,' he says, 'but I'm sure they're talking amongst themselves about things like HIV and homophobia. To me, that's part of my social justice work'to open the doors for people to have conversations they might not otherwise have.'

Want more breaking equality news & trending entertainment stories?

Check out our NEW 24/7 streaming service: the Advocate Channel!

Download the Advocate Channel App for your mobile phone and your favorite streaming device!

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

Before AIDS, gay artist Rex drew hot men on the prowl — then he disappeared

April 11 2024 3:15 PM

Diets that mimic fasting reverse aging: study

March 07 2024 5:28 PM

The Most Amazing HIV Allies & Advocates of 2023

November 03 2023 12:51 PM

PrEP without a prescription now a reality in California

February 06 2024 8:37 PM

This OnlyFans Star Is Trying to Raise $100K to Fight HIV

December 26 2023 3:05 PM

Injectable HIV treatment, prevention: Everything you need to know

March 26 2024 3:28 PM

The naked Black body takes center stage in this HIV campaign

January 03 2024 1:07 PM

8 dating tips for gay men from a gay therapist

March 21 2024 2:50 PM

Mr. Gay World wants to make sure you're OK

January 02 2024 4:56 PM

Plus: Featured Video

Latest Stories

The government failed on mpox. Ritchie Torres's new bill addresses that

April 18 2024 1:21 PM

On Anal Sex Day, crack up with The Bottom's Digest

April 18 2024 10:22 AM

Todrick Hall has long supported the communities he comes from

April 17 2024 12:02 PM

Our May/June issue of Plus is here!

April 17 2024 12:00 PM

Giselle Byrd is taking center stage — and helping others do the same

April 10 2024 2:24 PM

Discover endless fun at The Pride Store: Games & electronics for all ages

April 09 2024 4:25 PM

Mean Girls' Daniel Franzese on playing an HIV+ character

April 09 2024 3:57 PM

HIV-positive Air Force, Navy servicemembers victorious in lawsuit

April 09 2024 3:02 PM

Unlocking a new level of beauty with Dr Botanicals' ethical skincare line

April 08 2024 3:40 PM

Unleash your wild side with The Pride Store’s beginner’s guide to kink

April 08 2024 3:35 PM

Why are mpox cases in the U.S. on the rise again?

April 08 2024 1:30 PM

Happy national foreskin day!

April 04 2024 1:45 PM

Adult entertainment icons Derek Kage & Cody Silver lead fight for free speech

April 03 2024 3:06 PM

LGBTQ+ patients twice as likely to face discrimination: survey

April 02 2024 4:57 PM

Spring into The Pride Store’s top new arrivals for April

April 02 2024 4:39 PM

Nashville PD Must Pay HIV-Positive Man Denied a Job

April 01 2024 6:22 PM

Common has a message on how to foster self-love

March 29 2024 7:33 PM

Listen to Dr. Levine: Take syphilis seriously

March 28 2024 6:40 PM

Breaking boundaries in gender-free fashion with Stuzo Clothing

March 27 2024 2:15 PM