Photography by Jack Mannix

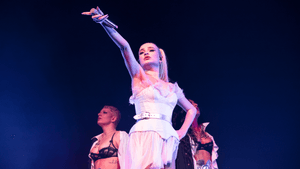

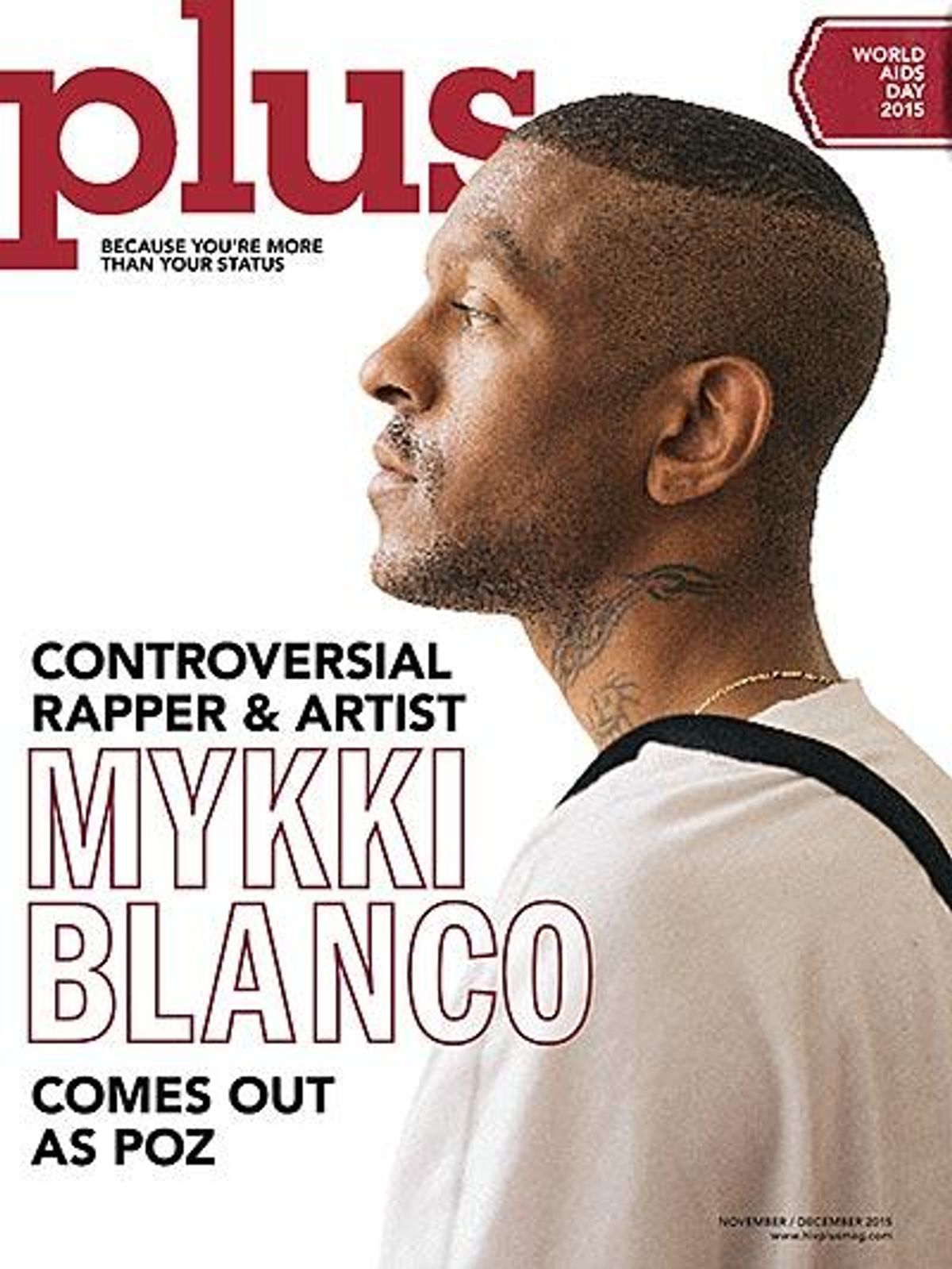

Mykki Blanco is a rapper and performance artist who is known to his thousands of fans as a gender-bending rebel, someone who is unafraid to be himself and push boundaries in an industry that often demands conformity.

A music video for one of his early songs, “Wavvy,” went viral, racking up over 1.5 million views to date, because it exemplifies this ethos. In the 2012 clip, Blanco raps as two different characters: the first, a shirtless thug trying to evade police capture; the second, a fabulous wigged and lipsticked entertainer singing in a posh nightclub.

“Oh this fag can rap? Yeah, they saying that. They listening,” Blanco lyricized about his entrée into a music scene known for its homophobia.

But unbeknownst to his fans, who praised him for being “brave” and having the “makings of a gay icon,” Blanco, whose birth name is Michael David Quattlebaum Jr., was living a different double life from the one depicted in his videos and concerts. For years, Blanco was closeted about being HIV-positive.

The coming-out process is difficult for any HIV-positive person. Many feel shame and fear the reactions of friends, family, acquaintances, possible romantic partners, and society, which still stigmatizes those who have contracted the virus.

For public figures, particularly those in the music industry, these problems are amplified. Coming out as positive becomes public record and a feature of news coverage. Attacks rooted in stigma can come from all angles, particularly in a world with social media, where anyone can post or tweet a hateful remark. In addition to harassment, there’s also the financial threat of the loss of a fan base and, ultimately, one’s livelihood.

For these reasons, hardly any living musicians are out as HIV-positive. There are exceptions — British New Wave artists Holly Johnson (Frankie Goes to Hollywood) and Andy Bell (Erasure), indie singer-songwriters John Grant and Byron Keith, and Styx bassist Chuck Panozzo. But all of these performers are white rockers and, for the most part, came out after having achieved success in their field.

Although he has achieved success — eight music videos, three EPs, three world tours, and the opportunity to open for A-list talent like Björk — Blanco feels like he is still in many ways just getting started. And the path ahead is uncharted. There are no major rappers or hip-hop performers who are out as HIV-positive. One of the most prominent to have lived with the virus, Eazy-E, whose story is depicted in the new film Straight Outta Compton, died of AIDS-related complications a month after his diagnosis.

Before his death, Eazy-E, who identified as straight, came out to his fans in a letter in order to raise awareness about HIV and how it is spread. He sought, in his own words, “to turn my own problem into something good that will reach out to all my homeboys and their kin, because I want to save their asses before it’s too late.… I have learned in the last week that this thing is real, and it doesn’t discriminate.”

Eazy-E died in 1995. Twenty years later, and there are still no black musicians who speak publicly about having HIV. Except for Blanco. He came out on Facebook this year during Pride season, a time when the LGBT community celebrates its identity.

“I’ve been HIV-Positive since 2011, my entire career. Fuck stigma and hiding in the dark, this is my real life. I’m healthy I’ve toured the world 3 times but I’ve been living in the dark, it’s time to actually be as punk as I say I am,” Blanco wrote, and followed it with another comment: “No more living a lie. HAPPY PRIDE.”

When Blanco posted this note, he did not anticipate the reaction he would receive. Over 12,000 people liked the post, and over 700 shared it. News of it went viral, and the story was covered both in LGBT media outlets, including The Advocate, and mainstream media, such as Time.

“I did it on this whole emotional whim,” Blanco says of his coming-out. “But I think afterwards, when Newsweek and Time magazine — who have never heard of me before — are writing about it, I’m like, ‘Oh, wait, maybe it’s been a while since someone’s done this.’ ”

When he’s asked how it feels to have such a secret off his chest, Blanco’s voice, which had previously been upbeat and energetic, becomes thick with emotion.

“I actually feel like a good person. And I don’t think I had felt like a good person in a really long time,” he says, before breaking down in tears.

Although the 29-year-old performer had come out as HIV-positive on a “whim,” Blanco admits he had been struggling with the emotional burden of his silence for years. He remembers how bleak his outlook was when he first received his diagnosis.

“I thought the world was over,” he recalls. However, he says, “I was not entirely surprised because I knew what I was doing in that period of my life — it was a very dark period — and I knew what I was doing to contribute to the high-risk behavior that led to it happening.”

Blanco, a survivor of child abuse, now understands that the cruelty he experienced then led to his taking actions that endangered his physical health, such as having risky sex with multiple partners.

At the time, he suffered from “feelings of low self-worth,” of “never being good enough,” and a “sense of abandonment,” and he sought “emotional love through physical love.” He describes his mind-set at the time as “obliviousness, when you want to be loved so bad that you start taking careless risks.”

For a year after learning he was positive, Blanco was afraid to have romantic partners, and he kept the news of his status to himself. “The best way to keep a secret is to tell no one,” he says. His mantra was a lesson learned from his childhood in the gossip-fueled South, specifically North Carolina, where he lived until he was 16. It took two years before Blanco told his mother, who had raised him single-handedly, and he did it in “the worst possible way… [during] a heated argument.”

“The reason I didn’t tell my mother for so long is because I didn’t think she’d be able to handle it,” says Blanco, who remembered her warnings about HIV and the importance of safe sex. “I think that for a lot of mothers who end up having gay sons, that is a fear.”

However, he found the reverse to be true. Although there were tears and an initial period of uncertainty, Blanco’s mother called him about a week later with a reassuring message.

“I’ve been doing a lot of reading. I’ve been doing a lot of praying. You’re gonna be OK,” Blanco recalls his mom telling him. And she made sure of it. She took charge of his health care and treatment, ensuring he made all of his medical appointments, which he admits he had been inconsistent in keeping before her support.

“I’m so glad I told her,” he says.

But even with support from his family, Blanco lived in a state of anxiety about his status and the social stigma attached to it. He worried that those he had sex with and disclosed his status to might tell the world he is HIV-positive and ruin his music career.

As a result, he sketched plans in his head — he would be closeted about it until he was 40 years old, he reasoned, or at least until he made a certain amount of money (the roving dollar figure somewhere in the millions). Depressed, he would sometimes tweet to his fans that he was considering leaving the entertainment world for, say, a career in journalism, a field away from the limelight where he could use his skills as a writer and activist.

As time went on, however, he realized that he could no longer keep a secret that he felt contradicted the punk ethos for which he publicly stood. To the world and to his fans, Mykki Blanco was a queer pioneer who was unafraid of challenging gender norms and defying conventions. Blanco had never had to come out about his sexual orientation.

“Everyone always knew I was gay. My father told me he knew I was gay when I was 3 years old,” he says. After a lifetime of transparency, the thought of staying in a closet about his HIV status, when he was perceived as so out and proud, was untenable. Moreover, he felt like it violated a trust with his fans.

“How shitty and how deceived would they feel if, 20 years from now, they found out I was HIV-positive but I was too afraid of the stigma to come out about it?” he asks. “What kind of fraud would I have been to all the people that supported me? All the people that are trans and positive? Who are gay and positive? Who have supported me and bought my music and come to my shows? I couldn’t be honest with myself enough, to love myself enough, [so] that self-love could then be encouragement or inspiration to them? No, no, no. Honestly, truthfully, I think I have too much integrity for that.”

“How shitty and how deceived would they feel if, 20 years from now, they found out I was HIV-positive but I was too afraid of the stigma to come out about it?” he asks. “What kind of fraud would I have been to all the people that supported me? All the people that are trans and positive? Who are gay and positive? Who have supported me and bought my music and come to my shows? I couldn’t be honest with myself enough, to love myself enough, [so] that self-love could then be encouragement or inspiration to them? No, no, no. Honestly, truthfully, I think I have too much integrity for that.”

Beyond his career, his relationship with his fans, and his public life, however, there was another factor that propelled Blanco to come out as HIV-positive.

“I did it for love. I did it for myself,” he asserts. “At a certain point, my real life has to be more important than this career. And at a certain point, my own happiness and my own loneliness, it overcame me.”

He’s looking for the same thing we all are.

“I want real love in my life. I don’t want love at 3 a.m.,” he says, pointing to lonely, late-night searches for romantic connections on hookup apps like Grindr. “I want someone who knows. I want positive guys who are positive to know that I am positive, so that they can approach me and that we can talk and there can be no awkwardness. I want negative guys to know so that I don’t have to have that awkward conversation with them anymore. Or if they really do like me, they know what they’re getting into.”

It also means setting new boundaries at home and while on tour. “I had made this rule for myself: I can’t hook up with groupies on tour,” he says. “But then I found myself in Berlin or in different countries or in bathhouses or part of a culture that I don’t condemn, but…that is not healthy for me. And so, I was like, You know what? I don’t want to be this person anymore.”

In addition, Blanco’s decision to come out came from a place of defiance against a world that told him from the onset that as “a gay black cross-dresser from a single-parent home, that I was not going to be able to be shit.”

Bracing for “another wave of stigmas,” he made the following resolution: “Guess I’m gonna have to do what I do best, which is challenging people’s expectations of what my limitations are going to be.”

Surprisingly, a source of strength for Blanco was the Kardashians, the ubiquitous reality TV family who have built a media empire through living their lives openly. In particular, Caitlyn Jenner — the former Olympian who came out as transgender earlier this year to much fanfare — became a “symbol of hope” to Blanco.

“Good God. That took so much courage,” Blanco says of Jenner’s decision to come out at the age of 65. Although he worries about Jenner’s impact on public perceptions of transgender people — as a wealthy conservative, she is the farthest thing from typical trans women, who face economic discrimination, violence, and an HIV rate nearly 50 times higher than that of the general population — he says that witnessing someone tell the story of decades suffering in the closet “gave me the push to come out.”

Throughout his journey, Blanco has also heeded the wisdom of the matriarch of the Kardashians, Kris Jenner, who as a mother cried after learning of her daughter’s sex tape in 2007, and as her manager realized, “All I knew was that I had to make some lemonade out of these lemons fast. Real fast,” as she would later tell the tabloid press.

There have been more than a few sour notes in the public reaction to Blanco’s coming-out. He speaks with exasperation of the “click-bait” headlines wondering if his fans will turn on him, a pair of comedians speculating on YouTube if his coming-out was a publicity stunt, and his frustration knowing that thousands of people who had never heard his music or understood his art were now judging, commenting on, and spreading misinformation about him. But he’s learned to take it with a grain of salt.

“I realize now that as my profile raises, I am going to start to have to understand that people will say ugly things, and that I’m not just in my little artsy community of people that understand what I’m doing, or in the indie world,” he says.

His profile has indeed risen in 2015. For the first time in his career, he signed with a label this year, !K7 Records, which will give his music an international reach. Blanco has even launched his own imprint on the label, Dogfood Music Group, which seeks to “disrupt” the “singular image of ‘African-American music’” in media, according to its mission statement.

His decision to come out as HIV-positive also earned him the admiration of !K7’s CEO, Horst Weidenmuller, who lost his brother to an AIDS-related illness in the 1980s.

His decision to come out as HIV-positive also earned him the admiration of !K7’s CEO, Horst Weidenmuller, who lost his brother to an AIDS-related illness in the 1980s.

“Mykki, you’re making such a political statement,” he told Blanco, though the rapper downplays his own impact still. An assertion that Blanco is saving lives by coming out elicits nervous laughter from the artist.

“You think so?” he says. “I don’t know about that. I don’t think I can take that on yet.”

But in many ways, he has already taken on that fight. Although Blanco initially feared becoming the “new poster child” for HIV, with requisite tours, lectures, and visits to hospitals, the process of coming out has enlightened him to the power of his voice and his visibility.

“It’s felt so liberating,” he remarks. “I find myself wanting to talk about it in a way that I never did.”

For Blanco, social media — the space where he came out — remains an essential forum for education and tearing down stigmas that surround those who live with the virus. It has been a learning experience for him as well. He recalls one instance where he temporarily fell into “a K-hole of insecurity” over whether or not to post a sexy picture of himself online, in part because he feared the judgments of those who would see it as perpetuating the behavior that led to his infection.

After an hour, he brushed these concerns aside. He posted the image along with an empowering message to others.

“Being HIV-positive doesn’t mean you don’t get to feel sexy or free or liberated,” he wrote. “It doesn’t silence you from talking about sex or having sex. Be safe. Be conscious. Be aware. But don’t let society make you feel like you can’t be sexy, or ashamed for being sexual. Stay safe. Stay free.”

Societal stigma toward HIV-positive people is one of Blanco’s greatest sources of outrage. “35 million people” is a phrase he repeats throughout his interview with Plus, a number that refers to the number of people living with HIV worldwide, as estimated in 2013 by the World Health Organization.

“Thirty-five million people? I hate to say it, but that’s enough to have it almost be normal,” he says. “I think 35 million people deserve to be treated with a sense of normalcy. I think 35 million people deserve to live in a world where they’re not fearmongered. I think 35 million people deserve to have the stigma lifted from their lives. I think 35 million people deserve to live in a country — to live in a world — where HIV-negative people don’t think they can turn their fucking nose up at us because we’re positive. Thirty-five million people is a lot of people.”

So why does stigma continue to exist, particularly in at-risk groups like African-Americans, in which women contract HIV at 20 times the rate of white women, and 60 percent of men who have sex with men will test positive by the time they turn 40?

“Because no one talks about it,” Blanco says point-blank, and that’s a problem that he is already striving to correct. Without naming the rapper, he also references the problem with hip-hop lyrics that glorify misogyny and unprotected sex. Blanco quotes the following lyrics, which a Google search reveals belong to ASAP Ferg, in his song “Shabba.”

“Run up in this shit raw, I got a girl,” Ferg sings. “I ain’t never got no fuckin’ condoms.”

Words like these have the unfortunate power to influence cultural norms and behaviors, and fuel misinformation about how HIV is spread. To counter this, Blanco says lyrics to his future songs will address HIV, as he believes that musicians and other influencers have a responsibility regarding the health of those who listen. His experience of coming out as HIV-positive has particularly awakened him to this duty.

“I know that when I talk about sexual things in my songs now, I’m going to have to. And to be honest, I’m not begrudged about that,” he says.

Even the more liberal-minded hipsters — whom he identifies as more of his audience than typical hip-hop fans — need to take responsibility, Blanco maintains, as he observes how straight people in this group are also negligent in safe-sex practices.

“If everyone wants to be so politically open, then they need to start being socially aware. And they need to start being health-conscious,” he says.

Despite press speculation that Blanco might lose his fans over the revelation of his diagnosis — and thus his ability to influence them about anything, much less health practices — the rapper insists that the opposite has already occurred. His bond with his listeners has never been stronger.

“The music industry has never given me anything,” he says. “I’ve always had to fight for it. I’ve always had to get it myself. And I’ve always had to get it organically. So if anything, this revelation has made my relationship with my fans closer.”

Though he hates to bring them up, Blanco again references the selfie-loving Kardashians as offering yet another guiding light in his journey toward honesty with himself and the world.

“We’re living in the age of transparency,” he says. “We’re living in a time where people kind of want to know all your business. To a lot of my fans, they actually feel like they know me now — or they know me better.”

Though Blanco acknowledges that he will make mistakes on the road ahead, he takes comfort in being as honest as he can be — with the world and with himself. The fears that plagued him before have lifted. And the future is bright with possibilities.

“I’m no saint. I’m no perfect person. I’m sure that something will happen or I’ll do something imperfect,” he concludes. “But right now I literally have nothing to hide. And it feels so amazing.”

“How shitty and how deceived would they feel if, 20 years from now, they found out I was HIV-positive but I was too afraid of the stigma to come out about it?” he asks. “What kind of fraud would I have been to all the people that supported me? All the people that are trans and positive? Who are gay and positive? Who have supported me and bought my music and come to my shows? I couldn’t be honest with myself enough, to love myself enough, [so] that self-love could then be encouragement or inspiration to them? No, no, no. Honestly, truthfully, I think I have too much integrity for that.”

“How shitty and how deceived would they feel if, 20 years from now, they found out I was HIV-positive but I was too afraid of the stigma to come out about it?” he asks. “What kind of fraud would I have been to all the people that supported me? All the people that are trans and positive? Who are gay and positive? Who have supported me and bought my music and come to my shows? I couldn’t be honest with myself enough, to love myself enough, [so] that self-love could then be encouragement or inspiration to them? No, no, no. Honestly, truthfully, I think I have too much integrity for that.” His decision to come out as HIV-positive also earned him the admiration of !K7’s CEO, Horst Weidenmuller, who lost his brother to an AIDS-related illness in the 1980s.

His decision to come out as HIV-positive also earned him the admiration of !K7’s CEO, Horst Weidenmuller, who lost his brother to an AIDS-related illness in the 1980s.