Editor's Note: We originally ran this article in 2014. We thought the occasion of National HIV/AIDS Long-Term Survivor's Awareness Day was a good one to reprint it.

History should always trump nostalgia because “nostalgia isn’t what it used to be.” Whoever first said these words — baseball icon Yogi Berra, French actress Simone Signoret, or New Yorker magazine writer Peter De Vries — they apply to the history of AIDS activism.

That said, I think each of us should be nostalgic for our own past because it’s our past, not because it’s more illuminating than the experiences of another era. Our past includes AIDS. When reflecting on AIDS history, we have an obligation to be honest about our conclusions without regard for political correctness.

Some shorthand is helpful when looking into our past.

First let’s acknowledge that the “told” history of AIDS in the U.S. is, so far, largely the history of gay, urban, white, middle-class men. It’s a statement of who had the resources during those horrible times to organize and apply pressure. Of course others were involved — women, minority activists — however, not many in leadership roles under the spotlight. There is an entire history yet to be told about the courageous roles played by men of color and the women of ACT UP.

A steady release of films has presented a partial, evolving perspective on AIDS history.

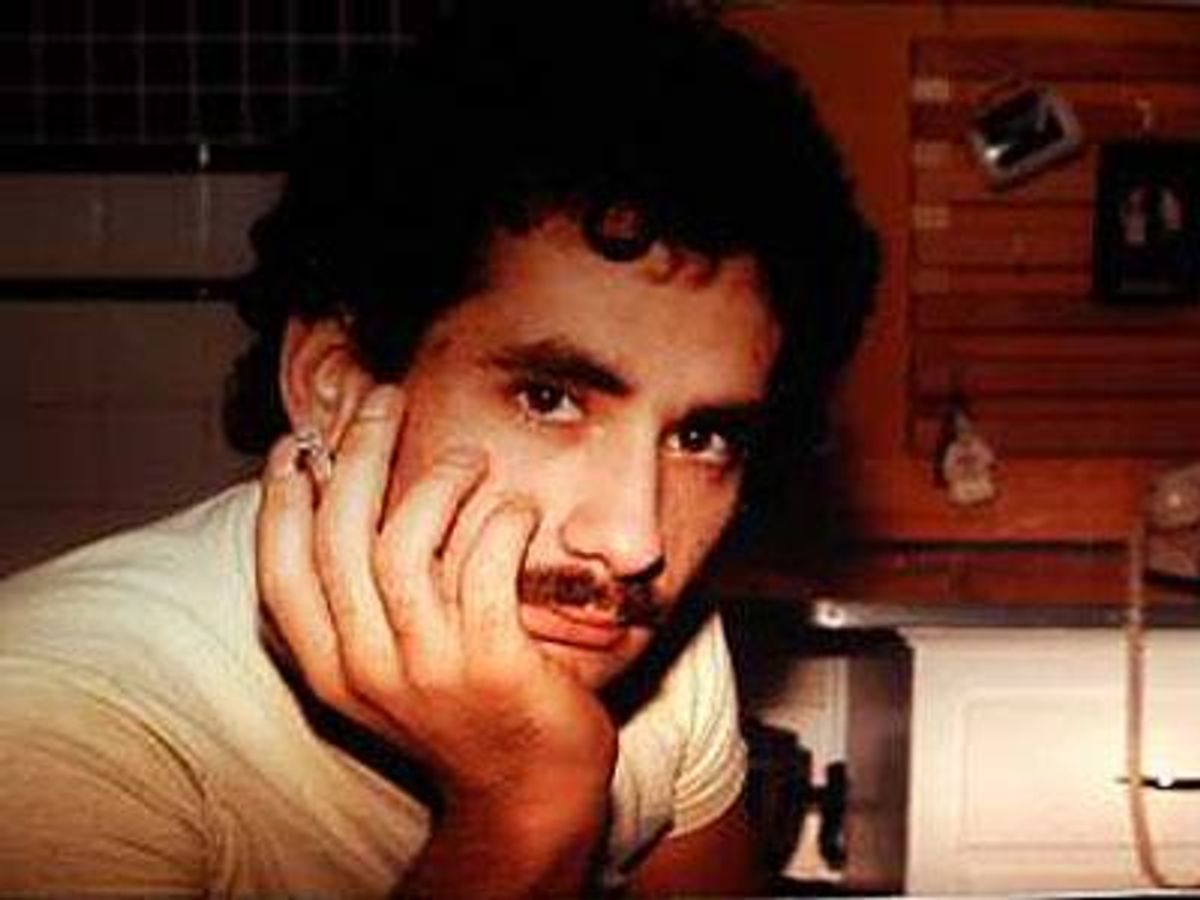

Gay Sex in the ’70s by Joe Lovett is about the obvious. How to Survive a Plague by David France is about white men taking up the mantle, for which we are all grateful. But it is not a complete history. Sex Positive, a film by Daryl Wein, about Richard Berkowitz, is a lucid delineation of New York City’s sexual revolution, mimicked in all major U.S. cities but, again, only about men. Sex in an Epidemic by Jean Carlomusto more fully covers various constituencies involved in ACT UP, for example, the courageous women, but we must tell more of their stories. Positively Naked, in which I participated, commemorates the 10th anniversary of Poz magazine and is a stunning visual portrayal by Spencer Tunick embracing most demographics affected by the virus. I have yet to screen United in Anger by Jim Hubbard and Sarah Schulman.

Each of these fine films covers only a portion of what is still a foggy history that is slowly being pieced together by survivors. To say so does not diminish their importance. They are not a complete AIDS history, and acknowledging that isn’t politically incorrect. It’s the truth.

Next, let’s admit that in the telling of any story gay men love to parse more than they love to shop. AIDS history is no exception. We’re the captains of “yes, but what about” knee-jerk reactions.

Finally, good men do the best they can when tested by events while others are immobilized. It’s part of the human condition. That’s why I do not have an AIDS ennoblement theory. All we know for sure is that untreated HIV makes you sick, then you die. HIV doesn’t make you a hero. If you were a reasonably well-adjusted individual before infection, you are likely a reasonably well-adjusted person after infection. If you were a big a-hole SOB before infection, you are likely a big a-hole SOB after infection. Sure, some people have an “AIDS epiphany,” i.e., stop abusing drugs, stop selling their bodies for sex, stop beating their girlfriends or boyfriends, start being faithful to mental health counseling, get honest about their sexual habits and why. Some do not have that epiphany. Whether or not a person has an “AIDS epiphany” has to do with what the individual brings to and/or learns from the experience. It has nothing to do with the virus. The virus doesn’t care about its host.

When people say, “My life is better with AIDS,” what I think they mean is that their diagnosis brought them face-to-face with some ugly, negative realities of their life .In that case, getting into housing, removing themselves from all sorts of risk — violence, sexual abuse, drug abuse — was an improvement in their life. Their life is better. Not because they got infected, but because infection forced them into a corner in which they face reality and acted accordingly.

Me, well, I was 18 in 1969 (Stonewall) and moving forward didn’t miss a thing. Hit New York City as often as possible, had lots of freelance sex, failed miserably at relationships because I didn’t have a clue about what a relationship between two men was all about or could be like. We had no role models. Each of us does the best we can with what life hands us, and with what we hand ourselves by our decisions, whether informed, uninformed, stoic or silly. In the end, we are all worthy human beings who deserve respect.

At left: How to Survive a Plague

At left: How to Survive a Plague

Still others use tragedies like AIDS to gain power through evil deeds, like Jerry Falwell, the religious right, then and now home to more closeted, self-hating gay homophobes than there are stars in their heaven. They are also part of the human condition. When I was a young man, a mentor told me the biggest homophobe is a gay homophobe. I didn’t understand then, but do now. Homophobia had a great deal to do with the spread of AIDS in the epidemic’s early years. Until recent years, and certainly before and immediately after Stonewall, the heterosexual dictatorship was in full control of the culture. Up against this oppression, gay men went underground and created an elaborate and efficient system of creating community, mostly a sexual community.

Post-Stonewall, we moved the underground labyrinth above ground and defiantly defined our liberation as sexual liberation. Since nothing happens in isolation, these twin forces — the sexual dictatorship and our response to it — created the perfect mechanisms for a public health storm. We did in closed and open spaces what our oppressors defined as a criminal act, a mental illness, or a sin. We fucked with pride.

For many, participation in the gay sexual revolution was the first time they felt connected and loved. For many, when AIDS first hit and activist groups formed all across the nation, many of those same gay men said the same thing — they finally felt connected to a community.

At left: Positively Naked

At left: Positively Naked

As we now begin to canonize AIDS history, do we as gay men, HIV-positive and HIV-negative survivors and our younger brothers, have the fortitude to look back and understand that no single aspect of a group of people — like defining liberation in only sexual terms — can pass for its whole? To look back honestly is not being sex-negative. It is being sex-positive. Knowing your HIV status in a timely manner and being honest about it with partners is sex-positive. Most new HIV infections occur within primary sexual relationships, not hookups, although that occurs. That means one or both partners in a primary relationship — fuck buddy, this week’s BF or whomever — do not know their HIV status. That’s sex-negative. We need to take responsibility for ourselves. If we stick our dick in an ass we cannot stick our head in the sand.

Regarding HIV testing and taking care of ourselves and our partners, when writing about the 30th anniversary of AIDS for Instinct magazine, I spoke with Richard Berkowitz, coauthor with Michael Callen in the ’80s of the first-ever safer-sex book, How to Have Sex in an Epidemic, and the man who encouraged them to write the book, Dr. Joseph Sonnabend. Berkowitz remembered how he and Callen spent six weeks drafting a 44-page masterpiece that Sonnabend read at his desk. He then raised his head and said, “You’ve written more than 40 pages about sex and never once mentioned love.”

In accepting a GLAAD Media Award for How to Survive a Plague, activist and film subject Peter Staley said, “Gay men are only about 2 percent of the U.S. population, but we’re the fastest growing group of new infections, 63 percent of total infections in recent years. Why aren’t these numbers shocking us?”

Recently released update figures from the Centers for Disease Control indicate the rate of diagnosis continues to increase within men who have sex with men (MSM) with a 11 percent rise in diagnoses from 2009 to 2011, resulting in an estimated 30,573 MSM being diagnosed with HIV in 2011 (up from 27,545 in 2009). This is in marked contrast to heterosexual diagnoses (for both males and females), with a 2.5 percent decrease in infections. Since Staley made his remarks, this new data, for 2011, shows that MSM as a percentage of new cases increased from 63 percent to 65 percent.

University of Pittsburgh researcher Ronald Stall says if current trends continue 50 percent of African-American men who turned 18 in 2009 and have sex with men will be HIV-positive by age 35. Fifty-four percent of all men who have sex with men will be HIV-positive.

So whether you’re on your way to pick out a wedding cake or to the bathhouse, it’s time to get tested. And remember to contribute something other than a hot load to the community. Being gay is about so much more than sex.

The movies and books that are in the current dialogue shaping the current AIDS canon reflect various aspects of collective experiences. Since no one of us is more than the sum of our cultural parts, no one of us can ever embody all the aspects of something as world changing as the spread of AIDS. I can’t possibly know what it would have been like to be a poor man of color without family and community support, without access to health care or insurance, and face AIDS. Neither can I expect him, without dialogue, to understand my experiences. That is why in this formative period of looking back on our collective AIDS history it is paramount we remain collective, loving, and embracing. As survivors and younger men interested in gay and AIDS history reflect on the past, we must not do to one another what the larger culture in an earlier time did to us as gay men. We cannot become our old enemy at this crucial time of looking back. Why? Because the epidemic is alive and well within younger gay/bi communities, especially communities of color. AIDS is not “history” there. Now is not the time for us as gay men to define ourselves by our differences but by our collective need for health, wellness, and a renewed sense of purpose as we construct our recent history.

Frank Pizzoli is a writer, editor, and producer. His work has appeared in Lambda Book Report, White Crane Review, Instinct, Poz, Rivendell’s Q Syndicate and Press Pass Q, HIV Plus, AlterNet syndication, Positively Aware, Body Positive, New York Blade News, and Washington Blade. He is the publisher and editor of Central Voice newspaper and founder of nonprofit Positive Opportunities Inc., a Points of Light Foundation award winner (2001). Read his interviews with Martin Duberman, Christopher Bram, and The Violet Quill: Edmund White, Felice Picano, and Andrew Holleran. This article is reprinted with permission from Lambda Literary Foundation and LamdbaLiterary.org, where it originally appeared.

At left: How to Survive a Plague

At left: How to Survive a Plague At left: Positively Naked

At left: Positively Naked