This new graphic novel for teens has a worthy goal but makes some troubling fumbles in its execution.

May 23 2013 7:00 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

AIDS in the End Zone is a one-of-a-kind graphic novel. Written by “the young men at the South Carolina Department of Juvenile Justice in Columbia, South Carolina,” it has the lofty goal of teaching the state’s teens, especially African-American boys, about HIV and AIDS in an engaging format with language they’ll understand.

This is a timely effort, as the state of South Carolina currently ranks eighth in the nation for new AIDS cases and the city of Columbia is sixth in the nation among metropolitan areas. The book, published by the University of South Carolina, was funded in part by grants, and there will be a study to determine its success in educating teens about HIV.

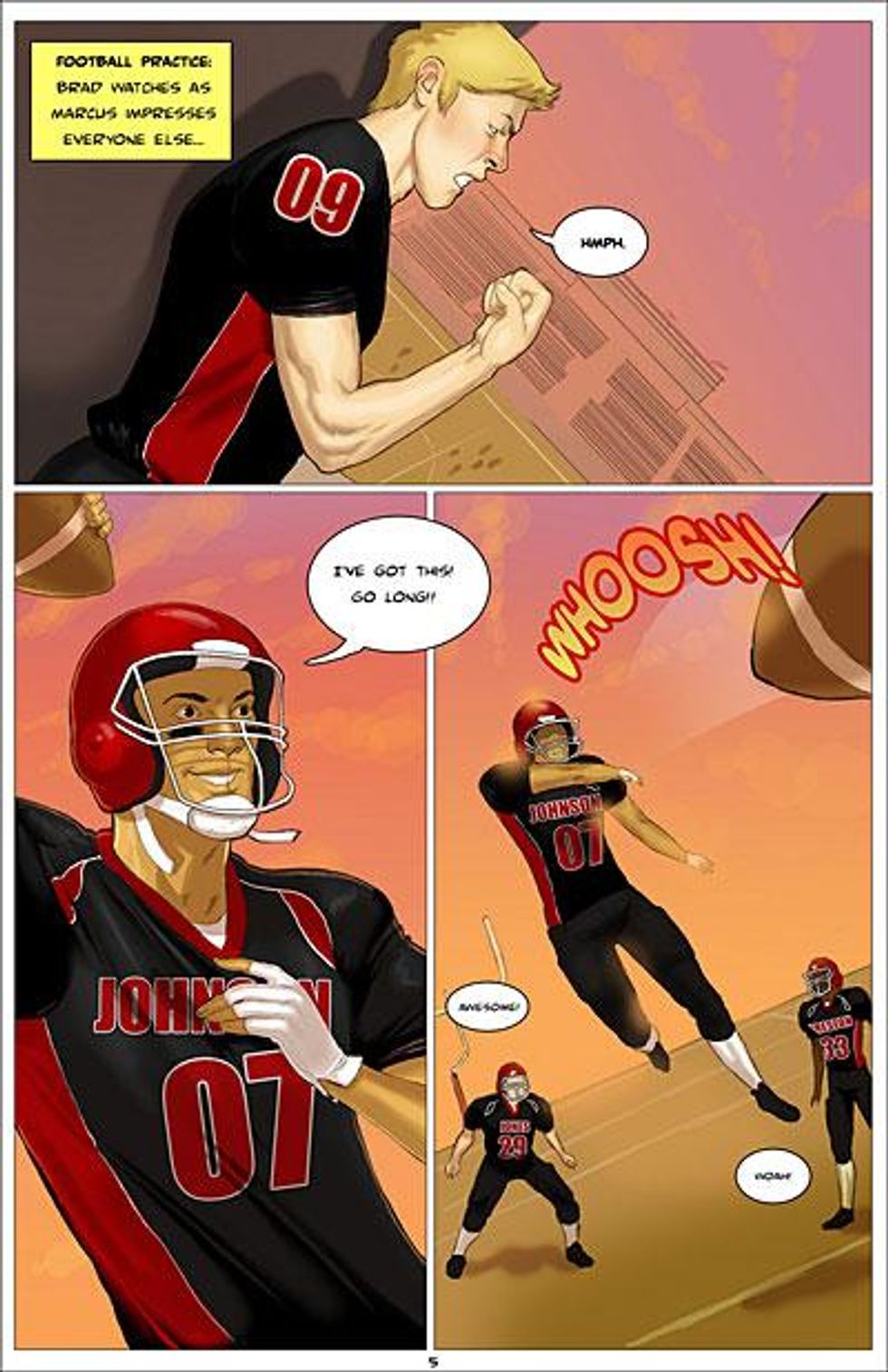

Two University of South Carolina School of Library and Information Science professors spent six months working with 15- to 19-year-old boys in the justice system to create the 30-page novel’s storyline, characters, and dialogue. One of these professors, Karen Gavigan, has focused on how graphic novels can be used to improve literacy among adolescent males, while her coeditor, Kendra Albright, has studied communication strategies used in Ugandan AIDS prevention efforts. S.J. Petrulis illustrated the book with full-color, realistic drawings.

AIDS in the End Zone is commendable for its effort and for including members of its target audience in its creation, but it is still flawed, and any recommendation for its use has to include suggestions for mitigating a number of troubling elements. The creators deserve props for showing teens that heterosexual sex can transmit HIV while also mentioning that “sexual contact with women or men, homosexual or heterosexual including oral and anal sex” are also modes of transmission (and clarifying that kissing, toilet seats, and sharing drinks are not).

But you can’t talk about this graphic novel without addressing its problems.

First and foremost, the title AIDS in the End Zone is really a misnomer. None of the characters have or develop AIDS. It should be called HIV in the End Zone. Using “AIDS” instead of “HIV” may provide a catchier title and it may draw more readers to open the book; but it confuses the issue by confounding HIV with AIDS. This is particularly damaging in a product designed to educate teens on HIV and AIDS.

The booklet also contains a short glossary, which includes a definition of AIDS as “the disease you get when your immune system fails.” his definition includes no indication of how HIV is related to AIDS; an odd omission, especially considering that one of the “Do You Know” sidebars that populate the book clearly states that AIDS occurs when “HIV destroys your immune system.”

The inside cover of AIDS in the End Zone provides a must-read key to the book’s characters. Rather than simply being there for review as in many graphic novels, here the key is essential reading (not to mention a shortcut to good storytelling) because it provides critical information about characters not revealed elsewhere in the book, including an introduction to a tiny red devil dressed entirely in white, who smokes and — while perched on other characters’ shoulders — tempts them to take stupid and/or morally reprehensible actions. The key describes the devil as “Id,” who “as the name suggests, is an ageless creature who always encourages the immediate gratification of all desires. Some consider Id to be the devil on your shoulder.”

The existence of the Id character in the story is problematic in itself, as it suggests that some external force or malevolent being leads the main characters astray, and thereby absolves the characters from responsibility for their own actions. But it also seems ridiculous that the editors chose to name the character “Id” and act as though their stated audience (urban teens) would be familiar with Sigmund Freud’s concept of the id. I can’t speak for all American teens, but as someone who foster parented 13- to 17-year-old boys in Portland, Ore., I can say that perhaps only one in 10 would be familiar with this Freudian structure of the psyche.

The plot of AIDS in the End Zone revolves around Marcus, a new student who sweeps in and snags the role of quarterback (not to mention the adoration of the high school’s girls) from former star Brad. Brad decides to get even by having Marcus sleep with Maria, who is HIV-positive.

When Brad initially approaches Maria, demanding, “You’re going to sleep with Marcus,” she protests, “I can’t do that! I’ll get in trouble!! Besides you broke up with me. You can’t boss me around anymore.”

This suggests that if they were still together. Brad could boss Maria around and use her indiscriminately, including as a sexual object to pass around (as though her sexuality actually belongs to him and is his to use or distribute as he chooses). In addition to being objectified and dehumanized by this depiction, Maria is revealed as someone who only cares about herself; she’s only worried about getting in trouble, not about passing HIV to another person.

I don’t doubt that this sentiment reflects the worldview of the teen boys who helped write this book, but anyone who questions this perspective on women will need to add their own educational addendum here. It also bears repeating, especially to young women, that no one, regardless of their relationship (boyfriend, girlfriend, even parent) has a right to insist that someone have sex with another person.

Despite her original objections, Maria agrees to Brad’s demands when he threatens to reveal her HIV-positive status. It may be telling that the Id character — who appears when Brad plans his revenge and when Marcus decides to go to the party where he’s set up with Maria — is strangely absent in scenes with Maria. No little devil whispers in her ear. And although she thinks “I can’t believe I have to do this” and seems bullied into the situation, she goes ahead and has sex with Marcus.

If you are a parent, caregiver, or service provider, you might want to pause on this scene and ask the teen in your life what Maria and Marcus should have done differently in the situation. Maria could have simply alerted Marcus to Brad’s despicable plan. She or Marcus could have insisted on using a condom. These choices might have derailed the storyline, but they should at least be suggested as smart alternatives to intentionally infecting someone with HIV (or having sex with someone because you’re being blackmailed).

The booklet does not mention other safe sex alternatives and it quickly follows the above with the conservative anthem, “The surest way to avoid HIV is to not have sex.” (It should be noted that Marcus could be seen as being punished — much like numerous sexually active women in horror films — for not choosing abstinence. Although, to be fair, he is not perfunctorily killed for his sexuality, as women tend to be in those narratives.)

Marcus didn’t use a condom and he does test positive for HIV, but that’s not the end of the story. Marcus responds angrily, even violently, to his test results. In fact, our “hero” is only prevented from striking Maria by the intervention of another character. Standing in a busy lunchroom, Marcus shouts, “She gave me HIV!!”

Meanwhile, Brad’s friend Sean breaks his silence about the plot — by snatching a microphone and announcing, to a football stadium full of fans, that Brad used Maria (you know, like a gun) to infect Marcus with HIV.

The only indication that Sean’s unilateral decision to publicly reveal that Maria and Marcus are HIV-positive might not have been the right choice is found at the bottom of the page of “Fast Facts,” included in the book’s additional materials. There the editors note, “HIV tests and their results are confidential.” This statement is clearly meant to encourage youths to get tested without fear. As the sentence continues, the results of HIV tests “will be shared ONLY with people authorized to see your medical records.” So you will need to make it clear that it was wrong of Sean to reveal Marcus’s and Maria’s HIV status to a stadium of people who had no business knowing the affected students’ private medical information.

After the plot is exposed, Brad is arrested. So is Maria, who doesn’t escape punishment despite arguably being a victim too (of bullying, blackmailing, outing, and being used sexually). In the end both Maria and Brad are charged with knowingly infecting another person with HIV.

Such laws really do exist and vary widely from place to place. In some jurisdictions an HIV-positive person can be charged with a crime even if that person had no detectable viral load, practiced safe sex, and didn’t pass the virus to their sexual partner(s). Help your teen research the laws in your state or municipality.

AIDS in the End Zone concludes with a flash-forward, seven years in the future, where Marcus is speaking at an “AIDS awareness” event. (Not sure why it’s an AIDS awareness event instead of an HIV awareness event, but whatever.) He says that living with HIV is hard, but “as an NFL quarterback I think I’m doing pretty well!” This effectively illustrates that being HIV-positive is not a death sentence and doesn’t mean one’s life is over, a nice way to end the story on a positive note.

Overall, AIDS in the End Zone is a commendable effort toward the prevention of HIV infection among teenagers — especially straight teens whose greatest risk is sexual transmission, not drug use. It features engaging illustrations and a compelling storyline. But it could have used another round of edits and suffers from some biased perspectives. I recommend sharing this booklet with the teens in your life, but doing so only while also providing additional information to mitigate its problems.