Treatment GuideJust DiagnosedSex & DatingAfrican AmericanStigmaAsk the HIV DocPrEP En EspañolNewsVoicesPrint IssueVideoOut 100

CONTACTCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2025 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

The USA Today: The Midwest

(Part 3 in a series of four articles taking regional overviews of the effects of HIV)

Lorraine Teel, executive director of the Minnesota AIDS Project, has a term for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 'witch-hunt.' She is referring specifically to the CDC's newly announced initiative that shifts federal funds from traditional HIV prevention outreach programs to those emphasizing widespread HIV antibody testing.

'Case finding is important,' Teel says, 'but case finding at the expense of everything else is a witch-hunt. It's really poor public-health policy.'

The CDC focus was announced by the agency on April 17 and fully detailed in the April 18 edition of the CDC's Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Federal health officials, noting that the number of new HIV infections has hit a plateau of about 40,000 per year, revealed a radical shift in nationwide HIV prevention efforts to slash that number. 'We can no longer accept the status quo when it comes to HIV/AIDS prevention,' Health and Human Services secretary Tommy Thompson said regarding the new prevention approach.

Among the specifics of the initiative are calls to make OraQuick rapid HIV antibody testing, which can produce results in about 20 minutes, a part of routine medical care for nearly all Americans; to expand on-site testing in at-risk communities; and to target prevention efforts toward HIV-positive people to help them not expose others to the virus. Identifying the estimated 180,000 to 280,000 Americans who are unaware that they are infected with HIV will reduce HIV transmissions, CDC officials say, because studies have shown that those who know they are HIV-positive are more likely to take steps to avoid infecting others.

Paying for Prevention

But Teel and many other AIDS activists and service providers throughout the widely rural Midwest view the CDC's new focus with uncertainty. A specific worry is that a planned shift of $90 million in federal grants in 2004 away from community-based groups that conduct traditional outreach and prevention programs to those emphasizing testing and prevention for positives could cripple safer-sex, condom distribution, and HIV awareness efforts in rural communities.

'There's so little prevention funding in Minnesota already that any cuts are going to have an enormous effect,' says Linda Brandt, executive director of the Minneapolis-based Rural AIDS Action Network. While the organization supports the CDC's efforts to expand HIV antibody testing and has been conducting a rapid test outreach effort since November, Brandt says funds for such programs should not be diverted from traditional outreach. 'We have only $1.2 million for prevention efforts for the entire state's 4 million people,' she says. 'That's about 25 cents per person. We're already underfunded, and any additional cuts will be horrible.'

David Munar, associate director for policy and communications at the AIDS Foundation of Chicago, worries that AIDS education and awareness campaigns could be in particular jeopardy. He points out that there is still a significant need to inform many rural residents'particularly youths'about HIV, how it is transmitted, why they may be at risk for infection, and how to protect themselves. 'Prevention services already aren't adequately doing a good job in delivering these messages in rural areas,' he warns.

Withdrawing funding from programs aimed at HIV-negative people, especially in areas with low HIV infection rates, also could penalize the very groups that helped keep those rates low, adds Doug Nelson, executive director of the AIDS Resource Center of Wisconsin. In Milwaukee County, Wis., the HIV infection rate has dropped 51% over the past decade, a decline Nelson attributes to traditional HIV prevention outreach.

While Nelson's organization plans to integrate the OraQuick tests into many of its outreach programs, he says the agency will also continue traditional prevention work. 'Those approaches have made a big difference, and I don't want to give them up,' he notes. 'It would be terribly shortsighted not to continue to support and sustain that infrastructure of prevention work.'

Teel believes the CDC's shortsightedness will ultimately result in rising HIV infection rates. 'When you take the mathematical inevitability that more people living with the virus will mean more transmissions and couple it with an end to proven prevention programs,' she warns, 'I think we'll see a rapid increase.'

Testing Versus Care

Inadequate funding for traditional prevention programs is only one of the Midwestern HIV groups' financial criticisms of the CDC initiative. Another goes to the very heart of the federal agency's goal of identifying more people who are HIV-positive'an overall lack of federal dollars for treatment programs these newly identified HIVers will need.

'I don't think it's ethical to talk about radically expanding testing services without an assurance that the dollars for services are right behind that,' notes Earl Pike, executive director of the AIDS Taskforce of Greater Cleveland. 'The system for AIDS care is strained to the limits right now. If you're talking about identifying thousands and thousands of folks who are positive and don't know it yet, and throwing them into the same inadequately funded centers of care, what you're proposing is a reduction in standards of care.'

Thomas Adams, executive director of the AIDS Foundation of St. Louis, has similar worries. Although he generally supports the CDC's new focus, he is concerned that unless Congress increases Ryan White Act funding for treatment programs, there will not be an adequate public safety net for those who test positive and cannot afford private care.

Teel foresees that the CDC's testing push will force AIDS Drug Assistance Programs throughout the Midwest to set up waiting lists, tighten eligibility requirements, and limit the number of drugs they provide to accommodate the influx of newly diagnosed patients, leaving many new HIVers with few treatment options. 'It's morally reprehensible; it's inhumane' to identify people who are infected and then deny them care, she asserts.

Counseling Concerns

While Midwestern AIDS groups vary in their overall reaction to the new direction taken by the CDC, virtually all are vehemently opposed to the agency-backed reduction in requirements for counseling prior to HIV antibody testing.

According to Ron Valdiserri, MD, MPH, deputy director of the CDC's National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention, the counseling guidelines were changed to remove any barriers that might discourage time-pressed health care providers from testing their patients. 'This isn't new,' he says. 'When we revised our counseling and testing guidelines in 2001, we recognized that in some settings health care providers might not have the time to do extensive pretest counseling.'

Nancy Glick, MD, an assistant professor of medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital in Chicago who is running one of four ongoing CDC-funded studies that offer rapid HIV testing to virtually all emergency room patients, backs the revised federal counseling guidelines. Glick says her staff is adequately trained in pre- and post-test counseling and is able to successfully limit pretest talks. 'If someone doesn't have risk factors,' she says, 'we'll just explain what the test is and go from there.'

However, Nelson and Brandt say the high level of counseling skill Glick reports in Chicago is not necessarily seen at health care facilities in other parts of the Midwest, particularly in small, rural communities, which make up the largest portion of the region. There, many medical professionals may find themselves administering their first HIV antibody tests without having had formal training in counseling.

To help alleviate that lack of expertise, both the Rural AIDS Action Network and the AIDS Resource Center of Wisconsin plan to provide counseling training and skills-building programs for area care providers. Training, however, will not be available in every state, and even when it is conducted, there are no CDC funds to support it, Brandt says.

'If we're going to start global testing, we need a massive educational effort and dollars to educate every physician, nurse-practitioner, physician assistant, and anyone else who may be administering the tests,' she says. 'We'd have to get to these people in more than 850 towns in rural Minnesota alone. That's a big job.'

Missed Opportunities

Also missing from the CDC's new guidelines are requirements for post-test counseling for those whose tests are negative, says Munar. Essentially, recipients of negative test results might simply be told they are not infected and little else. Glick says that approach makes sense given her staff's experience in delivering negative test results. 'Once people find out they're negative, they're pretty much out of there'if not physically, then mentally,' she notes.

But Brandt believes post-test counseling is just as important for people who test negative as it is for those who learn they are infected with the virus. 'It takes a lot of courage for a high-risk person to come in to take an HIV test,' she says. 'It's unconscionable to not educate them on how to reduce their risk in the future.'

Munar adds that with a likely loss of funding for programs conducting outreach to those who are HIV-negative, post-test counseling may be one of the few remaining opportunities to deliver safer-sex messages and risk-reduction strategies. 'Because the United States is a low-incidence country, most of the people who test will test negative,' he explains. 'By diminishing or delinking counseling from testing, you miss an enormous opportunity to give those large numbers of people the information and support they need to remain negative.'

Picking Priorities

Despite the concerns expressed by AIDS experts over some of the components of the CDC's initiative, there's still a growing belief that traditional HIV prevention and testing efforts may be losing their effectiveness and that some kind of change is needed. What is not clear is what that new direction should be'or whether the CDC has chosen the most effective path.

Some say a better first step would simply be for Congress to devote more federal money to virtually all HIV outreach and treatment programs, an unlikely scenario given ongoing efforts to curb the rising federal budget deficit. Adams and others believe that agencies involved in prevention work should begin to work together in order to stretch prevention dollars by eliminating similar programs and better identifying and jointly administering new outreach efforts. Others welcome at least parts of the CDC's new focus, particularly its recognition of the need to fund programs to encourage those already infected with the virus not to transmit it to others.

'One thing I am pleased about is that someone at the federal level is finally recognizing that people living with HIV are sexually active and have the right to a satisfying life that includes sexual expression and relationships,' Pike says. 'We ought to do everything we can to support these people to maintain their health and well-being and the health and well-being of others.' But, he adds, those efforts should be part of a multifaceted approach.

Nelson agrees: 'As much as this is needed, I really oppose the idea of the CDC putting all its eggs in one basket. I would hope the CDC [leaders] didn't have an 'Aha!' moment, where they believe this is the only way to solve the HIV incidence problem. They absolutely need to also keep supporting what works.'

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

BREAKING: Supreme Court rules to save free access to preventive care, including PrEP

June 27 2025 10:32 AM

Thanks to U=U, HIV-positive people can live long, happy, healthy lives

July 25 2025 2:37 PM

The Talk: Beyond the exam room

August 13 2025 3:15 PM

Plus: Featured Video

Latest Stories

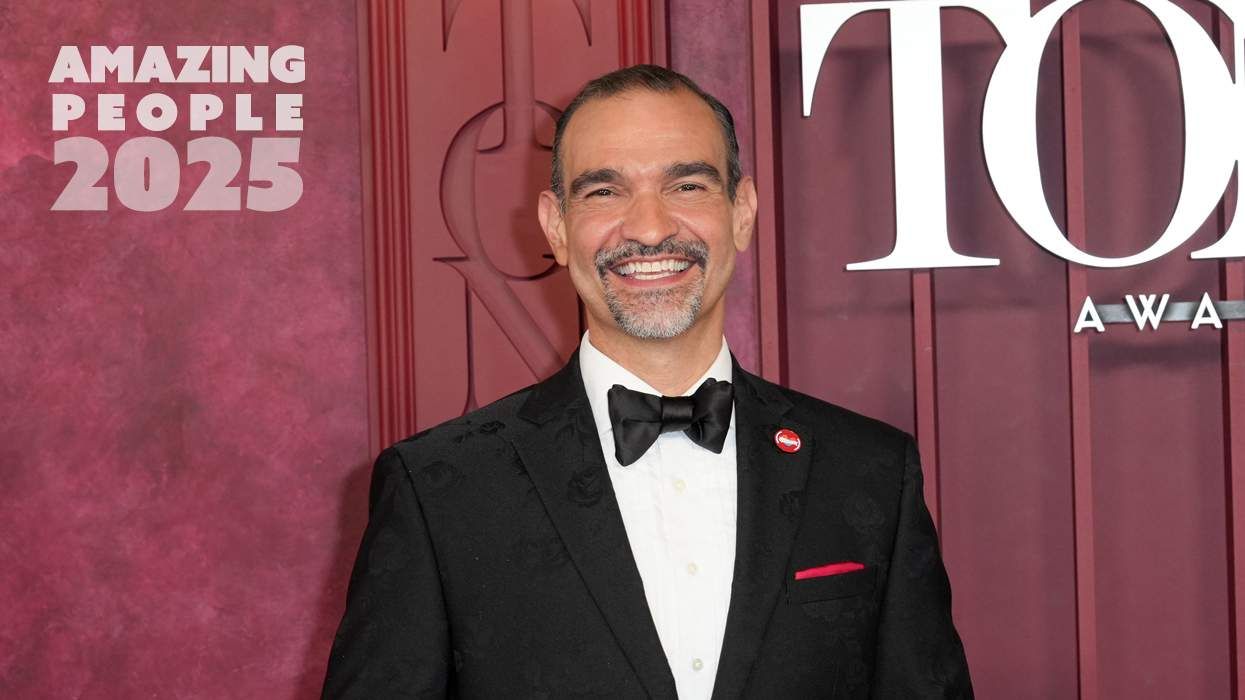

Amazing People of 2025: Javier Muñoz

October 17 2025 7:35 PM

It’s National PrEP Day! Learn the latest about HIV prevention

October 10 2025 9:00 AM

“I am the steward of my ship”: John Gibson rewrites his HIV narrative

September 16 2025 2:56 PM

“So much life to live”: Eric Nieves on thriving with HIV

September 03 2025 11:37 AM

The Talk: Owning your voice

August 25 2025 8:16 PM

The lab coat just got queer

August 21 2025 10:00 AM

Messenger RNA could be the key to an HIV vaccine — but government cuts pose a threat

August 20 2025 8:02 AM

The Talk: Navigating your treatment

August 01 2025 6:02 PM

The Talk: Starting the conversation

July 25 2025 4:47 PM

How the Black AIDS Institute continues to fill in the gaps

July 25 2025 1:06 PM

“I felt like a butterfly”: Niko Flowers on reclaiming life with HIV

July 23 2025 12:22 PM

Dancer. Healer. Survivor. DéShaun Armbrister is all of the above

July 02 2025 8:23 PM

1985: the year the AIDS crisis finally broke through the silence

June 26 2025 11:24 AM

VIDEO: A man living with HIV discusses his journey to fatherhood

June 10 2025 4:58 PM

Trump admin guts $258 million in funding for HIV vaccine research

June 03 2025 3:47 PM

Grindr is reminding us why jockstraps are so sexy and iconic

May 02 2025 5:36 PM

HRC holds 'die-in' to protest Trump health care cuts

April 28 2025 2:11 PM

Two right-wing Supreme Court justices signal they may uphold access to PrEP and more

April 21 2025 4:10 PM