Treatment GuideJust DiagnosedSex & DatingAfrican AmericanStigmaAsk the HIV DocPrEP En EspañolNewsVoicesPrint IssueVideoOut 100

CONTACTCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2026 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

'You cannot work here because you have HIV.' Those are words every HIV-positive worker fears. And despite laws prohibiting that very sort of discrimination'as well as more than 20 years of lessons about how it is impossible to transmit HIV in virtually every workplace setting'HIV-positive employees are still being fired, being denied promotions or employment, or being subjected to on-the-job harassment based solely on their serostatus. 'In some places there have been improvements, but we haven't made all the strides we need to make,' says Hayley Gorenberg, director of the AIDS Project of Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund. 'Workplace discrimination is still going on, and it's really tragic.' In fact, in just the past three years there have been several high-profile, attention-grabbing HIV discrimination cases. ' An HIV-positive acrobat was fired by Cirque du Soleil because his employers deemed him a health risk to other employees and customers of the glitzy circus. ' A former McDonald's manager received a $5 million jury award in a lawsuit against his employers for demoting and harassing him because he was HIV-positive. ' Two government employees were ultimately denied employment by the U.S. State Department solely because of their serostatus. Those cases are only the most visible ones'brought by people who challenged the discrimination they faced, says Leslie Cooper, a staff attorney of the American Civil Liberties Union's AIDS Project. Most instances of on-the-job mistreatment are never reported, much less confronted in court. 'If you lose one job due to your HIV status,' Cooper says, 'you are maybe not so keen to go to court and face the risk of becoming unemployable in your community.' A System With Weaknesses The people who do choose to fight workplace discrimination have had powerful federal laws'and often state-level protections'as their allies. In the 1998 U.S. Supreme Court case of Bragdon v. Abbott, the justices ruled that asymptomatic HIV infection is considered a disability under the Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990, giving HIV-positive people federal protections against discrimination. (Experts believe people with AIDS have always been covered by the ADA.) The Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which applies to agencies and groups receiving federal tax dollars, including the U.S. government, offers similar protections. Many states also have either broad or HIV-specific disability and antidiscrimination laws. Even the federal Family and Medical Leave Act, which guarantees workers up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave in any 12-month period, can be used for workplace accommodations, such as time off for HIV-related illnesses, says Deborah Weimer, a professor and director of the AIDS Legal Clinic at the University of Maryland School of Law. But the discrimination continues despite these legal protections, even at the very heart of the federal government that passed and enforces the two key laws, according to officials at Lambda and the ACLU. Lorenzo Taylor, a project officer for the Ryan White program at the Department of Health and Human Services, was aware that the State Department had a policy of rejecting HIV-positive applicants for the Foreign Service when he was recruited for an overseas job. But letters from two doctors stating he was in excellent health coupled with what appeared to be a more supportive atmosphere at the department'including calls by Secretary of State Colin Powell for workplace antidiscrimination and antistigma policies'led Taylor to believe his case would be an exception. He was wrong. After Taylor, who has lived with HIV for 19 years without any AIDS-related complications, disclosed his serostatus he was told his chances of employment were nil. 'They didn't even try to justify the policy' during the appeals process Taylor initiated when refused employment, he says. 'They mainly said, 'This is the policy, and this is the way things work in the Foreign Service''whether that's right or wrong.' The policy, enacted in 1985, bars HIV-positive applicants because at the time, according to the government, an HIV diagnosis usually meant imminent death and because Foreign Service workers could be assigned to countries with poor health care facilities. A second HIV-positive Foreign Service applicant, Kyle Smith, was similarly denied employment in November 2002. Lambda is representing both men in legal challenges. Smith's case is still working its way through government appeals processes; Taylor's has proceeded to a federal lawsuit. Calls to the State Department were not returned. With No Regard for the Science Jonathan Givner, the Lambda lead attorney on both cases, says the Foreign Service policy not only violates the protections offered by the Rehabilitation Act but also is so outdated that it does not reflect medical advancements that, for many, have turned HIV into a manageable long-term illness. 'By applying this litmus test and saying that no one with HIV is qualified,' Givner says, 'the State Department is ignoring medical fact and ignoring the legal requirements that every individual must be evaluated on his or her own individual merit, health, and history.' International circus troupe Cirque du Soleil similarly ignored medical facts when it fired HIV-positive acrobat Matthew Cusick, says Gorenberg, who is representing the 32-year-old man in legal proceedings. Cusick, who had given up his apartment, his job, and a budding relationship to relocate to Montreal for extensive training, was fired in April 2003, just three days before he was set to appear in Myst're, the company's Las Vegas show. The reason: He was deemed to pose an infection risk to his fellow performers, the circus crew, and audience members. 'I was shocked,' Cusick says of the company's reasoning. 'Before that I wasn't just on cloud nine; I was building cloud 10. My health was fine. I was cleared by two Cirque doctors for full participation. And then, just as I was about to start my dream job, they ripped it away from me.' Gorenberg says the Cirque case is unusual both because the company openly fired Cusick because of HIV''Very often we come across other excuses for firing the person, even though HIV is the motivating factor,' she notes'and because company officials apparently ignored expert advice that applied to Cusick's position. 'The World Health Organization, the National Collegiate Athletic Association, the National Basketball Association, the International Olympic Committee, the American Academy of Pediatrics all say there is no reason to exclude athletes with HIV,' she says. 'In more than 20 years there has never been a case of transmission of HIV in athletics. You'd think the fact that if people playing hockey and football aren't posing a risk to others, it should be applicable to circuses and acrobats.' After the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission ruled on January 30 that Cirque had likely engaged in illegal discrimination, the company relented and offered Cusick an unspecified performing position. At press time Cusick was uncertain if he would accept the new job or proceed with a possible federal lawsuit. Working to Circumvent the Law In contrast to Taylor's, Smith's, and Cusick's cases, others often involve not open, outright dismissal but more subtle forms of on-the-job prejudice and discrimination, say Cooper and Tamara Lange of the ACLU's AIDS Project, which released a report in November showing HIV discrimination to be occurring across the country. In Akron, Ohio, Russell Rich, a 24-year veteran of fast-food giant McDonald's, was forced to open his medical file to his bosses, given extra-long work shifts, and relegated from managerial to cashier duties when his employers learned he had HIV. (A $5 million jury award in his lawsuit against McDonald's was overturned in 2003 by an appeals court and the case remanded for a second trial.) A 19-year-old Nebraska woman in 2003 was fired from her job as a restaurant hostess, and in a second job she had stocking shelves at a convenience store, she had her work hours slashed and was forced to wear gloves, all because it was revealed she was HIV-positive. (She has since filed suit against both businesses anonymously as Priscilla Doe to keep her serostatus private.) People involved in other cases, like Hawaii postal worker Matthew Walker, also say requests for on-the-job accommodations, which are guaranteed under the ADA, are being illegally denied. Walker was suspended for 14 days and then later fired for forgetting to lock up his cash drawer and stamp book at the end of the work day. He says the hurried pace at closing time often made him forget about the items, and thus he formally requested an accommodation of an extra 15 to 20 minutes to properly close out his work station. Although he had letters from his medical doctor and a psychologist to support his request, the U.S. Postal Service never provided a response. And it turns out that his firing was unprecedented in the office, says Walker's attorney, Clayton Ikei. 'The USPS admitted that Mr. Walker is the only person, to their knowledge, ever terminated for not locking up his drawer at the end of the day,' Ikei notes. 'No other employee has ever been disciplined for it.' Walker, who now works in the naval shipyard at Pearl Harbor, lodged a complaint with the civil service and filed a lawsuit in U.S. district court seeking reinstatement to his job of nine years and $300,000 in punitive damages. Both cases are ongoing. Giving It Their All Cusick, Taylor, and Walker all say they opted to challenge the discrimination they faced both because of personal outrage over being treated as 'second-class citizens,' as Taylor puts it, but also to change the discriminatory policies that denied them the jobs they sought. Likewise, the ACLU attorneys say the Nebraska woman felt the treatment she received was wrong and that she needed to be publicly acknowledged. But dozens'possibly hundreds'of other cases of discrimination are never reported, say legal experts, either because workers are unaware of their rights or, more likely, do not want to face the hardships of legal proceedings, during which their HIV status could become much more public. 'Sometimes the emotional strain of it isn't worth it,' says Caryn Lubetsky, executive director of the Miami Beach, Fla.'based HIV Education and Law Project. 'I've had people I've talked with who I thought had really good claims, but they decided it wouldn't be worth the emotional toll.' Walker says he is aware of the legal and public difficulties he will face, but he says he is pressing on with his case to help raise awareness that HIV discrimination is wrong and illegal. 'The ADA was written to force people to have compassion,' he says, 'but I don't think you can do that with a law. It's hard to force people to have compassion. I do think you can make people more aware, though.' Lange agrees: 'Part of what we do is call into account employers caught discriminating so all companies can see there's a downside to discrimination, financially and morally, and learn of their responsibilities.' But it is not just awareness of the law that needs to increase, Givner says. 'There is still an enormous amount of ignorance and fear about people with HIV, how HIV is transmitted, and about the abilities of people with HIV to work,' he notes. 'Unfortunately, a lot of that is translated into discrimination in various forms in the workplace.' The remedy, Givner suggests, is ongoing education in the workplace on the basics of HIV, including how the virus is'and is not'transmitted. These messages also need to resonate outside of legal and business circles and be delivered in schools, churches, community organizations, and even within individual families, Givner adds. 'We need frank discussions about HIV and people with HIV,' he says. 'We need to eliminate the misinformation, ignorance, and fear of people with HIV. We as a society also need to recognize that people with HIV are not deserving of discriminatory treatment. We need to get that message across loudly and broadly.' You Should Know It is possible to challenge HIV-related workplace discrimination in court and not have one's serostatus made widely known, says Jonathan Givner, a staff attorney with Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund's AIDS Project. Legal complaints can be filed under a pseudonym, such as John Doe. In some cases, judges will allow court records to be sealed. 'It varies, depending on the court,' he says, 'but it certainly is an option, one that a lot of people don't know about.'

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

“So much life to live”: Eric Nieves on thriving with HIV

September 03 2025 11:37 AM

The Talk: Beyond the exam room

August 13 2025 3:15 PM

Messenger RNA could be the key to an HIV vaccine — but government cuts pose a threat

August 20 2025 8:02 AM

It’s National PrEP Day! Learn the latest about HIV prevention

October 10 2025 9:00 AM

Amazing People of 2025: Javier Muñoz

October 17 2025 7:35 PM

The lab coat just got queer

August 21 2025 10:00 AM

The Talk: Owning your voice

August 25 2025 8:16 PM

“I am the steward of my ship”: John Gibson rewrites his HIV narrative

September 16 2025 2:56 PM

Plus: Featured Video

Latest Stories

HIV-positive men stage 'Kiss-In' protest at U.S.-Mexico border

December 01 2025 12:56 PM

What the AIDS crisis stole from Black gay men

December 01 2025 6:00 AM

The Talk: Navigating your treatment

August 01 2025 6:02 PM

The Talk: Starting the conversation

July 25 2025 4:47 PM

Thanks to U=U, HIV-positive people can live long, happy, healthy lives

July 25 2025 2:37 PM

How the Black AIDS Institute continues to fill in the gaps

July 25 2025 1:06 PM

“I felt like a butterfly”: Niko Flowers on reclaiming life with HIV

July 23 2025 12:22 PM

Dancer. Healer. Survivor. DéShaun Armbrister is all of the above

July 02 2025 8:23 PM

BREAKING: Supreme Court rules to save free access to preventive care, including PrEP

June 27 2025 10:32 AM

1985: the year the AIDS crisis finally broke through the silence

June 26 2025 11:24 AM

VIDEO: A man living with HIV discusses his journey to fatherhood

June 10 2025 4:58 PM

Trump admin guts $258 million in funding for HIV vaccine research

June 03 2025 3:47 PM

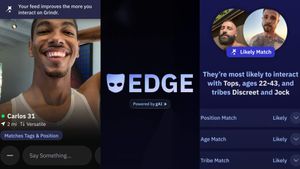

Grindr is reminding us why jockstraps are so sexy and iconic

May 02 2025 5:36 PM

HRC holds 'die-in' to protest Trump health care cuts

April 28 2025 2:11 PM

Two right-wing Supreme Court justices signal they may uphold access to PrEP and more

April 21 2025 4:10 PM

500,000 Children at Risk: PEPFAR Funding Crisis

April 08 2025 3:51 PM