Treatment GuideJust DiagnosedSex & DatingAfrican AmericanStigmaAsk the HIV DocPrEP En EspañolNewsVoicesPrint IssueVideoOut 100

CONTACTCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2026 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Think back to the first few days and weeks after you learned you had been infected with HIV. Your head was swimming with panic and fear. You were desperately hungry for information about where you could turn for help and what your next step for your health should be. Or perhaps, like many, you were simply numb with the shock of knowing that your future had been irrevocably changed. Now imagine that in the midst of that whirlwind of emotions you are also being asked by your health care provider or local health officials for information that some say might ultimately violate your privacy: You are requested to provide the e-mail addresses of your sexual contacts so that they can be urged to be screened for HIV infection themselves. That scenario is moving closer and closer from fiction to fact. Health officials in both San Francisco and Los Angeles, the latter in a pilot program backed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, are already using e-mail to notify sexual partners of adults testing positive for syphilis that they may have been exposed to the sexually transmitted disease. In a handful of cases in San Francisco in which other partner contact information is unavailable, the program has been extended to also cover people newly infected with HIV, notes Jeffrey Klausner, MD, director of sexually transmitted disease prevention and control for San Francisco's department of public health. Although the notification programs are currently focused almost solely on syphilis, they are designed to apply to any STD, including HIV, says Pragna Patel, the Epidemic Intelligence Services officer for the CDC's division of HIV prevention who is overseeing the Los Angeles effort. 'Part of the reason we put this study in [the CDC publication Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report] in February was to plant the seed for other health departments to use this methodology,' she says. Anonymous No More? Because the Internet is increasingly becoming the venue of choice for some adults'particularly gay and bisexual men'to meet casual sex partners, bringing partner-notification efforts into the digital age is simply a fight-fire-with-fire approach to disease control, health officials say. A 2002 San Francisco study shows that the Web, particularly chat rooms and sites catering to men seeking out sexual partners, has become the most common venue for hooking up'more popular even than bars, bathhouses, and sex clubs. Klausner estimates that today, eight or nine of every 10 gay and bisexual men in San Francisco arrange sexual encounters online. Because of the anonymity of the Internet'there is often no exchange of names, addresses, and telephone numbers, replaced instead by screen names and e-mail addresses'often the only contact information available is Internet-based, Patel says. San Francisco health officials have employed an e-mail notification program since 1999, Klausner says, when a cluster of new syphilis cases was traced to an America Online chat room called SFM4M'shorthand for 'San Francisco men for men.' Another cluster was later identified with and contacted through the sex hook-up Web site Manhunt.net. 'Now in the STD clinic we routinely ask people what e-mail handles they use online so that we can build up our public-health database,' he explains. The results of the e-mail programs are encouraging, both Patel and Klausner say. San Francisco officials say that up to 80% of people who receive syphilis notifications online contact the health department. Case studies reported from Los Angeles show that up to one half of the sex partners of men diagnosed with syphilis responded to e-mail health warnings. Studies conducted in Minnesota and Chicago also provide evidence of the effectiveness of online partnernotification efforts. Andrew Delicata, formerly of Chicago's Howard Brown Health Center, found online communication'particularly contact in Internet chat rooms'to be effective in getting seven of eight people who were contacted into STD testing. Through online contact, Minnesota health department staff members were able to urge 30 of 50 Internet users exposed to HIV or other STDs into care. The Wrong Way to Go? Despite these successes, though, not all AIDS advocates have rushed to endorse the online programs. Some even outright oppose the idea because the insecure and unreliable nature of digital communication could throw off the delicate balance between public health and personal privacy. 'It's completely unacceptable,' says Achim Nowak, a gay man who has been HIV-positive for 15 years and who wrote an essay about HIV disclosure issues in the book Voices From the Edge: Narratives About the Americans With Disabilities Act. 'I don't think any doctor or any agency has the right to report unwelcome medical information to someone who has engaged in behavior they may be ambivalent about, feel shameful about, or may be in the closet about.' Rhonda Goldfein, executive director of the AIDS Law Project of Pennsylvania, has a more pressing worry: 'How can you guarantee the e-mail doesn't reach someone it shouldn't reach?' The health notices, she points out, could unknowingly be sent to someone's place of business, where employers or coworkers may have access to them, or sent to a single e-mail account used by an entire family. Patricia Kummel, Ph.D., the director of the David Geffen Center for HIV Prevention and Health Education at New York City's Gay Men's Health Crisis, also worries about the insecure nature of e-mail communication. 'People can get each other's passwords and share e-mail addresses, and it's just not confidential,' she says, adding that only when security could be bolstered'much the way online merchants do with credit card information'should AIDS organizations consider such programs. E-mail mix-ups do occasionally happen, Klausner admits, and sometimes messages reach unintended recipients. 'If it's an incorrect recipient,' he says, 'we try to find out how we made the mistake, and maybe that person can help us to identify the correct recipient. If we're unable to do that, it's no different than if I left a voice mail on someone's phone or sent a letter'we apologize for the mistake.' The Nature of the Beast One possible explanation for such errors lies in the fluid nature of online communication, where Internet users commonly add and delete e-mail addresses, employ different user names on different Web sites, and shuffle between several screen names on services offering instant chat capabilities. Discarded screen names and e-mail addresses also can be later claimed by others. At America Online, for example, deleted screen names of current users and old screen names of former users can be registered by someone else after several months, according to AOL spokesman Andrew Weinstein. Most other e-mail service providers also recycle user names after a given period of nonuse. Yahoo spokeswoman Terrell Karlsten says the company periodically reviews and puts registered but inactive U.S. e-mail addresses back into circulation. With syphilis notification programs the likelihood that e-mail addresses will have changed hands is slim because of the rapid onset of disease symptoms. But for HIV, which can be diagnosed anywhere from weeks to years after infection, the long symptom-free window can make online contact information for those exposed to the virus decidedly unreliable. There is also the possibility that an e-mail with the incorrect domain address'using Hotmail's instead of Yahoo's, for example'will reach an unintended recipient. And even a slight juxtaposition, addition, or subtraction of letters in an e-mail address or screen name'such as 'readyforsex' instead of 'ready4sex,' or 'nycstud' instead of 'nystud,' 'nycstudd,' or even 'studnyc''can divert the health warning to the wrong user. But far more serious privacy breaches also are possible. Klausner refers to one incident in which a syphilis notice was meant to be sent simultaneously to several sex partners of the same man through the blind-carbon-copy function, which hides the addresses of the recipients. Instead, the e-mail was delivered as 'unblinded,' allowing all 25 recipients to see the e-mail addresses of everyone else receiving it. Ample Protections? Errors of that magnitude are extremely rare, Klausner says. 'We stress the importance that each individual's identity is protected,' he explains. Part of those safeguards is to never publicly identify the person testing positive for the STD that prompted the e-mail notification. 'We always say that 'We believe you've been exposed to HIV''or syphilis or chlamydia''and advise you to get a checkup,' ' he explains. 'The original patient information is never revealed,' even if the e-mail recipients call the health department and are correctly identified as a sex partner of the infected person. Patel says the Los Angeles syphilis notification program also shields the name'or online identifiers like the screen name or e-mail address'of the person testing positive for the infection. In addition, Patel says, the title line of the e-mail warnings is deliberately vague'at least from her and her colleagues' perspective'saying only 'Urgent Health Matter' because of confidentiality concerns. The body copy of the e-mails is only slightly more explanatory. The San Francisco notices give only department contact information and explain that a staff member would like to discuss an important health issue with the recipient, Klausner says. Part of the reason for the indirectness is to move as quickly as possible from online communication to conversations on the telephone or in person before STD-related information is discussed, according to Klausner. 'We prefer a face-to-face interview over a telephone interview over information shared online,' he explains, both because privacy is better ensured and because it is more comforting for the person being contacted. Nothing Like the Direct Approach But that reassuring in-person communication, which Goldfein says should be the cornerstone of any type of partner notification program, is the piece of the e-mail puzzle she believes is sorely'and cruelly'missing initially. 'It's like dropping a bomb on someone,' Goldfein says of suggesting someone may be infected with HIV or another STD and not having counseling immediately available. Nowak agrees. 'When I found out I was HIV-positive in December 1998 I talked with a counselor. I was meeting with a person and had chosen to take the test, but it still was incredibly emotional,' he explains. 'To have that information forced on you'I don't care how well-intentioned it may be'it's completely unconscionable.' Klausner and Patel disagree, as do other AIDS experts who note that HIV and STD partner notification programs already use regular mail, telephone communication, and inperson meetings to alert individuals that they may be carrying a serious infection. They say e-mail is simply an extension of those existing efforts. Lee Klosinski, director of programs at AIDS Project Los Angeles, also believes e-mail 'is an innovative way of using the same technology that brings people together to notify them of potential STD exposure and is a really smart thing to do.' But he says some AIDS activists and treatment advocates are not ready to embrace STD electronic-notification programs that also include HIV. 'That isn't to say we won't be there someday, but I think this is an area that is perhaps overly cautious about innovation,' he notes. Goldfein, however, remains unconvinced that online notification efforts should ever be widely used. 'There's just too many scenarios where someone's privacy could be compromised,' she says. 'Public health is always a trade-off'a balance of good against the harm. I think there's a greater likelihood of harm here. Besides, if you really want to protect me, don't send me an e-mail that says I've made a mistake and put myself at risk. E-mail me about safer-sex practices, e-mail me with information I can use to help myself. E-mailing me that the anonymous sex I had could have given me HIV doesn't protect me.'

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

“So much life to live”: Eric Nieves on thriving with HIV

September 03 2025 11:37 AM

The Talk: Beyond the exam room

August 13 2025 3:15 PM

Messenger RNA could be the key to an HIV vaccine — but government cuts pose a threat

August 20 2025 8:02 AM

It’s National PrEP Day! Learn the latest about HIV prevention

October 10 2025 9:00 AM

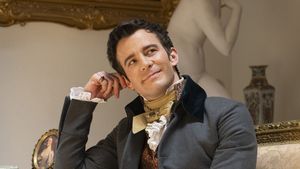

Amazing People of 2025: Javier Muñoz

October 17 2025 7:35 PM

The lab coat just got queer

August 21 2025 10:00 AM

The Talk: Owning your voice

August 25 2025 8:16 PM

“I am the steward of my ship”: John Gibson rewrites his HIV narrative

September 16 2025 2:56 PM

Plus: Featured Video

Latest Stories

HIV-positive men stage 'Kiss-In' protest at U.S.-Mexico border

December 01 2025 12:56 PM

What the AIDS crisis stole from Black gay men

December 01 2025 6:00 AM

The Talk: Navigating your treatment

August 01 2025 6:02 PM

The Talk: Starting the conversation

July 25 2025 4:47 PM

Thanks to U=U, HIV-positive people can live long, happy, healthy lives

July 25 2025 2:37 PM

How the Black AIDS Institute continues to fill in the gaps

July 25 2025 1:06 PM

“I felt like a butterfly”: Niko Flowers on reclaiming life with HIV

July 23 2025 12:22 PM

Dancer. Healer. Survivor. DéShaun Armbrister is all of the above

July 02 2025 8:23 PM

BREAKING: Supreme Court rules to save free access to preventive care, including PrEP

June 27 2025 10:32 AM

1985: the year the AIDS crisis finally broke through the silence

June 26 2025 11:24 AM

VIDEO: A man living with HIV discusses his journey to fatherhood

June 10 2025 4:58 PM

Trump admin guts $258 million in funding for HIV vaccine research

June 03 2025 3:47 PM

Grindr is reminding us why jockstraps are so sexy and iconic

May 02 2025 5:36 PM

HRC holds 'die-in' to protest Trump health care cuts

April 28 2025 2:11 PM

Two right-wing Supreme Court justices signal they may uphold access to PrEP and more

April 21 2025 4:10 PM

500,000 Children at Risk: PEPFAR Funding Crisis

April 08 2025 3:51 PM