Treatment GuideJust DiagnosedSex & DatingAfrican AmericanStigmaAsk the HIV DocPrEP En EspañolNewsVoicesPrint IssueVideoOut 100

CONTACTCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2026 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

When it comes to analyzing the level of leadership from the federal government on AIDS policies during the pandemic's 23-year history, treatment advocate Julie Davids does not mince words. 'I wouldn't call it 'leadership' at all,' she says assertively. 'I call it forced compliance by people with HIV and their allies.' Davids, who is the executive director of the New York City'based Community HIV/AIDS Mobilization for Power and a 14-year member of Philadelphia's chapter of ACT UP, is not alone in her bleak assessment of how federal officials have responded to AIDS on the domestic and'only recently'international front. Many activists and even key federal officials say AIDS leadership from the White House has often been sorely lacking. Even members of Congress and government health officials have spotty records of support, particularly when it comes to ponying up funds for HIV prevention efforts, treatment, and support services. 'The kindest thing I can say about our national leadership as a whole is that it's been uneven at best,' says Jeff Graham, executive director of Atlanta's AIDS Survival Project. 'While there have been some heroes on the national scene, there has also been a lot of problems.' HIV Plus enlisted the input of several advocates on HIV-related issues, and they gave us 10 key areas in which they say the federal government'in many cases the president in office at the time'has failed on AIDS policy since the dawn of the pandemic and what, if anything, can be done by the next administration to remedy these shortcomings. 1. Failure to use federal funds to support needle-exchange programs Although activists say the domestic battle against AIDS made the most progress under President Clinton's eight-year watch, they fault the former president for one of the biggest HIV prevention blunders: He rejected needle-exchange programs as a way to cut infection rates among injection-drug users. [See our feature on whether needle-exchange programs are successful on page 27.] 'This had more science behind it than most other prevention approaches we know,' says Gene Copello, MD, executive director of the AIDS Institute. But Clinton bowed to pressure from Republicans in Congress to uphold the ban on federal funding of the programs. 'Since leaving the White House, he has said one of his biggest regrets is not having lifted the funding ban,' says David Munar, an associate director at the AIDS Foundation of Chicago. It is still not too late to stem HIV transmissions among injection-drug users, who, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, account for 16% of the nation's new HIV cases. A profile of Democratic presidential candidate John Kerry on www.aidsvote.org indicates he has said he would do away with the federal funding ban via executive order if elected in November. George W. Bush, however, opposes needle-exchange programs, having called them 'misguided efforts to weaken drug laws' during the 2000 election campaign, notes the AIDS Vote site. 2. Failure to adequately challenge the notion that AIDS is a gay disease spread through immoral acts One of the reasons activists say former president Ronald Reagan did not publicly acknowledge the AIDS crisis until 1987'six years and 16,489 deaths after it had begun'was because it affected primarily gay men and transmission was linked to gay sex. 'We saw a lot of passing judgment and interesting terminology of whether someone 'deserved' HIV' because of how it was mainly being spread, says Bruce Garner, an AID Atlanta board member and a former member of the Ryan White HIV Planning Council for the Atlanta metropolitan area. Some people say that attitude not only sanctioned discrimination against gay men but also led sexually active heterosexuals'who today account for 35% of all new HIV infections, according to the CDC'to believe they were not at risk for the disease. While homophobia has waxed and waned in the nation's capital throughout the pandemic, and federal leaders always could'and should'do more to combat discrimination against gay men, AIDS groups also need to continue to push for such efforts, Davids says. 'In a country where HIV remains mainly a disease of queer people and poor people,' she notes, 'we need to be attending to all the areas of government policies that affect all our lives.' 3. Failure to provide ongoing federal funding of HIV prevention efforts In addition to not speaking about the AIDS pandemic for more than six years, Reagan also failed to adequately allocate federal funds for HIV prevention programs, including those that promoted condom use, even after HIV was discovered in 1984, activists say. 'I believe had the government responded more quickly in the early years, particularly in terms of prevention, it may have been able to stem some of the epidemic,' says Judith Billings, an HIV-positive woman and a member of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV and AIDS from 1996 to 2002. That inadequate federal support has continued through the pandemic, right up to this day, advocates say. 'With 40,000 new infections each year since 1992, the CDC's prevention budget has not grown to address that,' says Greg Smiley, a consultant with the American Academy of HIV Medicine and a PACHA member in 2000 and 2001. The solution is simple, activists say: Significantly boost HIV prevention spending; do not overemphasize 'prevention for positives' programs at the expense of proven, traditional outreach efforts; and do not divert precious funds from comprehensive HIV and sex education funds to those that promote abstinence only. 'We also need to understand that what worked in 1983 doesn't work in 2004,' says Paul Kawata, executive director of the National Minority AIDS Council. 'We have to be able to shift the paradigm to address current prevention issues.' 4. Failure to expand Medicaid to cover HIVers who have not received an AIDS diagnosis While Medicaid provides medical care for about 40% of the nation's adults living with AIDS and up to 90% of American children with AIDS, its benefits apply only to people with HIV disease that has advanced to an AIDS diagnosis. A bipartisan group of federal lawmakers hopes to change that through the Early Treatment for HIV Act. Introduced in the Senate by Republican Gordon Smith and Democrat Hillary Rodham Clinton'and similarly championed in the House of Representatives by minority leader Nancy Pelosi, Republican James Leach, and several others'the proposed law would give each state the option to amend its Medicaid laws to include all low-income HIV-positive people. Studies have shown that one benefit could be a 60% reduction in the death rate of HIV-positive people on Medicaid. The bill was introduced in both houses of Congress in 2003 but has yet to come to a vote. Kerry, a senator from Massachusetts, is a cosponsor of the bill and says he would sign the measure into law if elected president. It is unclear whether President Bush supports the legislation. 5. Failure to significantly focus on medical and support services beyond anti-HIV drugs Although boosting federal spending on the nation's cash-strapped AIDS Drug Assistance Programs is a major goal for activists, there is a growing worry that the George W. Bush administration's financial backing of other support programs and services for HIV-positive people is in even greater jeopardy. 'The Administration'does not seem to have at all an understanding that a lifetime of intense chemotherapy requires a lifetime of commitment and support,' Graham says. He urges the next administration and members of Congress to significantly boost spending on non'medication-related government programs for HIVers, including services provided through parts of the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency Act, the federal Housing Opportunities for Persons With AIDS program, and others. 'Under the current administration,' he says, 'we've seen those programs all get relegated to this 'bastard stepchild' support-services category and made to seem as though they're fluff.' 6. Failure to increase funding of resources for uninsured and underinsured HIVers Perhaps the biggest criticism leveled at George W. Bush's record on AIDS is that he has consistently sought to curtail spending increases for the nation's Ryan White Act. 'What everyone needs to understand is that 'flat-funding' [appropriations for a new year] really means a decrease,' Kawata says. 'There are always more and more people diagnosed with HIV and more and more people who need these services. That means you have less money to take care of all the HIV patients than you did the year before.' Sadly, the problem is likely to continue. The Ryan White act, originally passed in 1990, must be renewed every five years and is up for reconsideration in 2005. Bush has already sent a budget proposal to Congress seeking only slight increases for some Ryan White programs'such as ADAPs and the Minority HIV/AIDS Initiative'while funding the majority of other services at 2004 levels. A House subcommittee endorsed Bush's plan in July. Activists reacted to the spending proposals with alarm. 'Like most Americans, our lawmakers on Capitol Hill believe AIDS is no longer a domestic problem, that we've conquered AIDS, and that it's an issue only severely affecting the southern part of Africa,' Munar says. 'We have our work cut out to remind them that we still have a thriving and deepening AIDS epidemic and still have huge gaps in our care system.' 7. Failure to effectively use the presidency as a bully pulpit for AIDS issues 'When political leaders speak out on tough issues like AIDS, things change,' Copello says of the president's power to draw the nation's attention to the AIDS pandemic. 'When it's on the national radar screen, when the president and high-ranking political leaders speak on AIDS, people do listen.' But the White House bully pulpit has been used to address HIV-related issues with considerably varying degrees of success during the past four presidential administrations, say advocates. 'Reagan barely discussed AIDS at all, and George Bush didn't talk about it very much,' says Kenneth Mayer, MD, medical research director at Fenway Community Health in Boston and an AIDS caregiver since the first days of the pandemic. 'Clinton had a few excellent talks and speeches on AIDS, but a lot of people would say there wasn't enough follow-through.' George W. Bush gets mostly poor grades from activists on drawing attention to the domestic AIDS crisis, although he is widely praised for being the first president to focus public interest on the global pandemic by talking about it in his 2003 State of the Union address. Now, advocates say, both Bush and Kerry should similarly strive to raise interest about AIDS at home. 'If both candidates were to make AIDS a central issue of the campaign, regularly talk about it, make trips to clinics and treatment centers, and mention AIDS at conventions, there would be real action,' Smiley says. 8. Abandoning comprehensive HIV prevention methods for abstinence-only outreach Another major criticism of George W. Bush is his push for abstinence-only sex education in HIV prevention programs'often paid for at the expense of comprehensive prevention efforts, which promote condom use and safer sex'despite studies showing that abstinence programs are largely ineffective. 'We had a generation of people who grew up underinformed [about comprehensive HIV prevention] under Clinton, and now we have a new generation growing up totally uninformed,' Davids says. Abstinence-until-marriage programs also are irrelevant for gay men, still the largest at-risk group for HIV infection in the nation, she adds: 'It has nothing to say to gays except 'Drop dead.' ' Worse yet, many activists say officials in the Bush administration are pandering to the president's conservative voter base by questioning the effectiveness of condoms and accusing some AIDS groups of undermining prevention goals by encouraging sexual activity. 'AIDS has always been political,' Copello points out, 'but the difference today is that we're having to constantly justify the science of HIV prevention and the science of studying human sexuality. That is a big concern of mine and of many people's.' Bush, in his 2004 State of the Union address, urged a doubling of federal spending on abstinence programs to more than $270 million in 2005. A candidate questionnaire on www.aidsvote.org says Kerry supports and will increase funding for comprehensive HIV prevention and sex-education programs. 9. Failure to rely more on the surgeons general'the nation's top health experts'to educate the public about HIV Throughout the AIDS pandemic the U.S. surgeons general have been among the most proactive and effective leaders in the domestic AIDS battle, according to advocates. C. Everett Koop (who held the post from 1982 to 1989), Joycelyn Elders (1993'1994), and David Satcher (1998'2002) are commonly cited as being among the nation's best AIDS leaders. For example, Koop, who served under Reagan, in 1986 issued the nation's first federal report on AIDS, characterizing the disease as a public-health crisis instead of a moral or political matter. He also personally wrote 'Understanding AIDS,' a brochure mailed to 107 million U.S. households in 1988, the largest public-health mailing ever done. 'I think the federal government started speaking about AIDS because of Koop,' Copello says. But the work of the nation's surgeons general on HIV issues during the past 23 years has been mostly behind the scenes'and sometimes only in a minimal capacity even then, experts say. 'The surgeon general has a limited ability and not a very big budget, and that's been problematic,' Mayer says. 'But they have a great bully pulpit. Unfortunately, it has not been used very effectively.' 10. Deemphasizing the role of the president's AIDS advisory council in shaping national HIV policy The Presidential Advisory Council on HIV and AIDS, formed in 1995 under President Clinton, was for several years one of the most powerful engines driving federal AIDS policy. Former council member Billings says the panel was 'very proactive' in the 1990s, pushing for federal funding of needle-exchange programs and urging the Administration to devote more money to HIV prevention programs. The group also wasn't afraid to criticize the president when necessary, even at one point taking a no-confidence vote on Clinton, Billings says. But the election of George W. Bush in 2000 brought sweeping changes to the council. The Administration at first considered disbanding PACHA, but after an outcry from AIDS groups the White House instead moved to stack it with pro-abstinence, anticondom ideologues, say AIDS activists. New PACHA executive director Pat Ware 'made some pretty interesting choices [for replacements],' says former council member Smiley, 'including at the time some people who were considered to have no AIDS policy experience and to have iffy credentials at best.' Over time the council was reduced to little more than a rubber-stamp group, Munar asserts. 'That office today seems to be just a puppet group, and its decisions have no impact on how policy is set,' he notes. 'That's a shame, because getting good feedback from an expert panel and having advocates inside on an issue as important as HIV/AIDS is about the only way you can make some progress.'

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

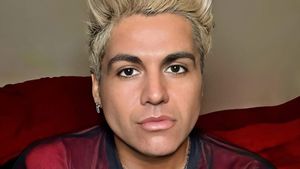

“So much life to live”: Eric Nieves on thriving with HIV

September 03 2025 11:37 AM

The Talk: Beyond the exam room

August 13 2025 3:15 PM

Messenger RNA could be the key to an HIV vaccine — but government cuts pose a threat

August 20 2025 8:02 AM

It’s National PrEP Day! Learn the latest about HIV prevention

October 10 2025 9:00 AM

Amazing People of 2025: Javier Muñoz

October 17 2025 7:35 PM

The lab coat just got queer

August 21 2025 10:00 AM

The Talk: Owning your voice

August 25 2025 8:16 PM

“I am the steward of my ship”: John Gibson rewrites his HIV narrative

September 16 2025 2:56 PM

Plus: Featured Video

Latest Stories

HIV-positive men stage 'Kiss-In' protest at U.S.-Mexico border

December 01 2025 12:56 PM

What the AIDS crisis stole from Black gay men

December 01 2025 6:00 AM

The Talk: Navigating your treatment

August 01 2025 6:02 PM

The Talk: Starting the conversation

July 25 2025 4:47 PM

Thanks to U=U, HIV-positive people can live long, happy, healthy lives

July 25 2025 2:37 PM

How the Black AIDS Institute continues to fill in the gaps

July 25 2025 1:06 PM

“I felt like a butterfly”: Niko Flowers on reclaiming life with HIV

July 23 2025 12:22 PM

Dancer. Healer. Survivor. DéShaun Armbrister is all of the above

July 02 2025 8:23 PM

BREAKING: Supreme Court rules to save free access to preventive care, including PrEP

June 27 2025 10:32 AM

1985: the year the AIDS crisis finally broke through the silence

June 26 2025 11:24 AM

VIDEO: A man living with HIV discusses his journey to fatherhood

June 10 2025 4:58 PM

Trump admin guts $258 million in funding for HIV vaccine research

June 03 2025 3:47 PM

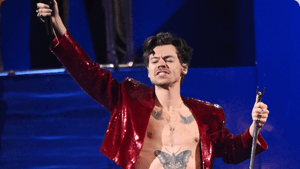

Grindr is reminding us why jockstraps are so sexy and iconic

May 02 2025 5:36 PM

HRC holds 'die-in' to protest Trump health care cuts

April 28 2025 2:11 PM

Two right-wing Supreme Court justices signal they may uphold access to PrEP and more

April 21 2025 4:10 PM

500,000 Children at Risk: PEPFAR Funding Crisis

April 08 2025 3:51 PM

Trending stories

Recommended Stories for You