Treatment GuideJust DiagnosedSex & DatingAfrican AmericanStigmaAsk the HIV DocPrEP En EspañolNewsVoicesPrint IssueVideoOut 100

CONTACTCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2026 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

In a sunny conference room in midtown Manhattan, Dumisani Rebombo's eyes sparkle as he describes his work in the fight against HIV in South Africa. He is nothing less than elegant. His lilting speech conveys an unusual patience, and his cotton candy'pink shirt draws attention to his tender face. Rebombo, a 46-year-old activist, came of age in the rural northeastern part of the country under the brutal apartheid regime. He is well versed in what he and his colleagues frame as South Africa's 'twin epidemics' of HIV and gender violence, having firsthand knowledge of the latter. He readily reveals that he's committed shocking acts of sexual brutality. In his teens Rebombo took part in a gang rape. He later sexually assaulted a woman, whom he then married on learning that she was pregnant with his daughter. As deplorable as Rebombo now realizes his actions were, though, they are not uncommon in a culture where women are devalued'and still far too often the targets of violence and sexual assault. 'I don't know how many times I've heard women scream in my street, and no one intervened,' he says, 'because in the back of your mind, this is how women are supposed to be treated.' It is unusual, however, that Rebombo speaks so openly of his past actions, which occurred in a society where gender roles have been rigidly defined. Perhaps more important, though, he has undergone a transformation of sorts that fuels his AIDS activism. He now turns to those defining events of his past to help shape the future of South Africa. 'What apartheid had been doing to all of us is what men were doing to women,' he says he's now realized. He and his peers also now know that any successful effort to stop the spread of HIV in his country must simultaneously work to reduce violence against women. Becoming Better Partners On a recent visit to both New York City and Washington, D.C., Rebombo joined Andrew Levack, director of Men as Partners, to promote the pioneering program and to explore the possibility of bringing it to the United States. Under the auspices of EngenderHealth, a global reproductive health organization, MAP helps men to challenge traditional concepts of masculinity in an effort to minimize physical and emotional suffering as a result of HIV, to increase their involvement as active partners in promoting health and ending gender-based violence, and to reduce the actual rate of infection'all while working within the framework of the realities of South Africa. Upward of 5.5 million South Africans, in a nation of approximately 47 million people, live with HIV, according to the United Nations. More than half of those with HIV are female, and fully 29% of all pregnant South African women who visited clinics in 2006 were HIV-positive. The United Nations estimates that in 2005 alone 320,000 South Africans died of AIDS. And to complicate matters, the South African government has a history of inertia in embracing medically proven treatments for HIV as well as an earlier connection to charlatans who denied the link between HIV and AIDS. As a senior program MAP officer in South Africa, Rebombo confronts these formidable challenges on a daily basis. But his path to AIDS activism was not without turbulence. He points to the gang rape in which he participated at the age of 15 as resulting from peer pressure, strictly defined notions of masculinity, and a culture where conflict was resolved through violence. His friends had ridiculed him for not being the 'boy,' he says, because he did 'women's work' by helping his sisters with their chores at home. Rebombo's stormy worldview began to shift years later, when he volunteered at his church and worked at a health clinic. He says he heard women recount how they were forced into unsafe sex. He had never previously given serious thought to the violence around him, he adds, yet began to connect the men's behavior to the severe health and emotional repercussions for the women. And for the first time in his life, he began to realize there were consequences for his actions. As time passed, Rebombo became convinced that to stop the spread of HIV in South Africa, health educators must see men not only as perpetrators but also as part of the solution to the social evil. To that end, he sought out EngenderHealth and its MAP program. He began his training with MAP in 2001, five years after its creation. Transforming Cultures Men as Partners' impact has been nothing less than transformative in AIDS-ravaged South Africa; the World Health Organization has commended MAP and similar programs for reducing violence against women and the spread of HIV. A study of the program in Soweto has shown that men who participated in MAP were more likely to get tested for HIV antibodies and much more likely to share the results with their partners. Workshops that explore gender roles have always been at the core of the program, now under way in 15 nations in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, Levack says. Each program is tailored to the needs of the specific countries, which range from Bolivia to Tanzania. For instance, in Nepal, a country with one of the world's highest rates of maternal mortality, MAP has trained male peer educators to encourage other men to accompany their partners to prenatal care and to recognize warning signs of pregnancy complications. In the International Journal of Men's Health, Levack outlines how MAP specifically effects change in South Africa. He cites workshops aimed at changing knowledge, attitudes, and behavior; the mobilization of men to take action in their own communities; the use of media as a tool to promote changes in social norms; and the collaboration with other nongovernmental organizations and grassroots groups to strengthen their ability to implement the program. Funding for the organization in South Africa comes from the governments of South Africa, Canada, and Sweden, private foundations, and the U.S. government's President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. To maximize its effectiveness further, MAP partners with other South African advocacy organizations, including those for gay men and lesbians. 'When men have an opportunity to engage in this program, they can find life more fulfilling,' Levack says. He calls the South Africa MAP model the 'first and one of the most progressive.' Part of its success is due to Rebombo, who lends an authenticity in educating men and training future advocates. He is the embodiment of a man who has altered his perceptions and has challenged stereotypes of masculinity, two of MAP's multifaceted goals. On a deeply personal note, he is so close to his daughter that when she began to menstruate, she told him before she told her mother. 'Traditional ideas about masculinity can be harmful to women and men in developing countries,' Rebombo says of his commitment to promoting gender equality. 'One can learn to be responsible and one can want to stay responsible. That, to me, is transformation. We need to spread the word.'

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

“So much life to live”: Eric Nieves on thriving with HIV

September 03 2025 11:37 AM

The Talk: Beyond the exam room

August 13 2025 3:15 PM

Messenger RNA could be the key to an HIV vaccine — but government cuts pose a threat

August 20 2025 8:02 AM

It’s National PrEP Day! Learn the latest about HIV prevention

October 10 2025 9:00 AM

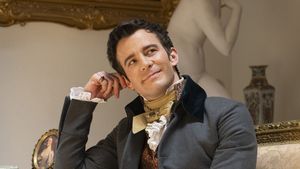

Amazing People of 2025: Javier Muñoz

October 17 2025 7:35 PM

The lab coat just got queer

August 21 2025 10:00 AM

The Talk: Owning your voice

August 25 2025 8:16 PM

“I am the steward of my ship”: John Gibson rewrites his HIV narrative

September 16 2025 2:56 PM

Plus: Featured Video

Latest Stories

HIV-positive men stage 'Kiss-In' protest at U.S.-Mexico border

December 01 2025 12:56 PM

What the AIDS crisis stole from Black gay men

December 01 2025 6:00 AM

The Talk: Navigating your treatment

August 01 2025 6:02 PM

The Talk: Starting the conversation

July 25 2025 4:47 PM

Thanks to U=U, HIV-positive people can live long, happy, healthy lives

July 25 2025 2:37 PM

How the Black AIDS Institute continues to fill in the gaps

July 25 2025 1:06 PM

“I felt like a butterfly”: Niko Flowers on reclaiming life with HIV

July 23 2025 12:22 PM

Dancer. Healer. Survivor. DéShaun Armbrister is all of the above

July 02 2025 8:23 PM

BREAKING: Supreme Court rules to save free access to preventive care, including PrEP

June 27 2025 10:32 AM

1985: the year the AIDS crisis finally broke through the silence

June 26 2025 11:24 AM

VIDEO: A man living with HIV discusses his journey to fatherhood

June 10 2025 4:58 PM

Trump admin guts $258 million in funding for HIV vaccine research

June 03 2025 3:47 PM

Grindr is reminding us why jockstraps are so sexy and iconic

May 02 2025 5:36 PM

HRC holds 'die-in' to protest Trump health care cuts

April 28 2025 2:11 PM

Two right-wing Supreme Court justices signal they may uphold access to PrEP and more

April 21 2025 4:10 PM

500,000 Children at Risk: PEPFAR Funding Crisis

April 08 2025 3:51 PM