Treatment GuideJust DiagnosedSex & DatingAfrican AmericanStigmaAsk the HIV DocPrEP En EspañolNewsVoicesPrint IssueVideoOut 100

CONTACTCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2026 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

HIV might undergo changes in the genital tract that make the HIV-1 strain in semen different from what it is when it's in the bloodstream, according to a study led by researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Worldwide, much of the transmission of HIV-1 is through sexual contact, men being the transmitting partner in the majority of cases. The new findings are significant because the nature of the virus in the male genital tract is of central importance to understanding the transmission process and the selective pressures that might affect the transmitted virus. Ultimately, it is the transmitted virus that must be blocked by a vaccine or microbicide. 'If everything we know about HIV is based on the virus that is in the blood'when in fact the virus in the semen can evolve to be different'it may be that we have an incomplete view of what is going on in the transmission of the virus,' says Ronald Swanstrom, Ph.D., a professor of biochemistry and biophysics and of microbiology and immunology at the UNC School of Medicine. In the study, published in August in the online journal PLoS Pathogens, Swanstrom and his colleagues compared viral populations in blood and semen samples collected from 16 men with chronic HIV-1 infection. Using single genome sequencing, they analyzed the gene coding for the major env protein, located on the surface of the virus, in the samples. The differences between the viruses from the two sources were striking, Swanstrom says. 'The sequence differences between the blood and the semen were like a flashing red light; it was a big hint about the biology of virus in the seminal tract,' he explains. 'In some men the virus population in semen was similar to that in the blood, suggesting that virus was being imported from the blood into the genital tract and not being generated locally in the genital tract. However, we found two mechanisms that significantly altered the virus population in the semen, showing that virus can grow in the seminal tract in two different ways.' In the first, he says, one to several viruses are rapidly expanded over a short period of time so that the viral population is relatively homogeneous compared to the complex population in the blood. In the second the virus replicates in T cells in the seminal tract over a long period of time, creating a separate population of virus that is both complex and distinct from the virus in the blood. To find out why these mechanisms are at play, the researchers then measured the levels of 19 cytokines and chemokines'proteins secreted by cells that control the immune system'in both the blood and semen samples. They discovered a significant concentration of these immune-system modulators in the semen relative to the blood, which could boost viral replication by creating an environment where target cells are kept in an activated state. Swanstrom's laboratory is now exploring whether evolutionary selection for some special property of the virus is occurring in the seminal tract that does not happen in the blood. 'While [we don't know] how these differences change the biology of the virus or if these changes are important for the transmission process,' study author Jeffrey Anderson says, 'it is clear that the virus in the blood does not always represent the virus at the site of transmission.' Knowing how the virus in the semen is different, the researchers say, could be an important part of understanding the puzzle of how HIV is transmitted.

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

“So much life to live”: Eric Nieves on thriving with HIV

September 03 2025 11:37 AM

The Talk: Beyond the exam room

August 13 2025 3:15 PM

Messenger RNA could be the key to an HIV vaccine — but government cuts pose a threat

August 20 2025 8:02 AM

It’s National PrEP Day! Learn the latest about HIV prevention

October 10 2025 9:00 AM

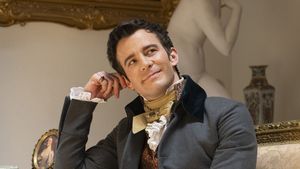

Amazing People of 2025: Javier Muñoz

October 17 2025 7:35 PM

The lab coat just got queer

August 21 2025 10:00 AM

The Talk: Owning your voice

August 25 2025 8:16 PM

“I am the steward of my ship”: John Gibson rewrites his HIV narrative

September 16 2025 2:56 PM

Plus: Featured Video

Latest Stories

HIV-positive men stage 'Kiss-In' protest at U.S.-Mexico border

December 01 2025 12:56 PM

What the AIDS crisis stole from Black gay men

December 01 2025 6:00 AM

The Talk: Navigating your treatment

August 01 2025 6:02 PM

The Talk: Starting the conversation

July 25 2025 4:47 PM

Thanks to U=U, HIV-positive people can live long, happy, healthy lives

July 25 2025 2:37 PM

How the Black AIDS Institute continues to fill in the gaps

July 25 2025 1:06 PM

“I felt like a butterfly”: Niko Flowers on reclaiming life with HIV

July 23 2025 12:22 PM

Dancer. Healer. Survivor. DéShaun Armbrister is all of the above

July 02 2025 8:23 PM

BREAKING: Supreme Court rules to save free access to preventive care, including PrEP

June 27 2025 10:32 AM

1985: the year the AIDS crisis finally broke through the silence

June 26 2025 11:24 AM

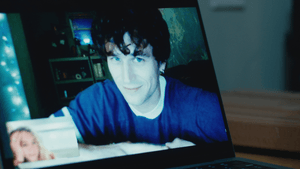

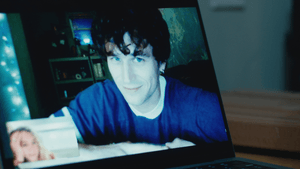

VIDEO: A man living with HIV discusses his journey to fatherhood

June 10 2025 4:58 PM

Trump admin guts $258 million in funding for HIV vaccine research

June 03 2025 3:47 PM

Grindr is reminding us why jockstraps are so sexy and iconic

May 02 2025 5:36 PM

HRC holds 'die-in' to protest Trump health care cuts

April 28 2025 2:11 PM

Two right-wing Supreme Court justices signal they may uphold access to PrEP and more

April 21 2025 4:10 PM

500,000 Children at Risk: PEPFAR Funding Crisis

April 08 2025 3:51 PM

Trending stories

Recommended Stories for You