Treatment GuideJust DiagnosedSex & DatingAfrican AmericanStigmaAsk the HIV DocPrEP En EspañolNewsVoicesPrint IssueVideoOut 100

CONTACTCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2026 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

In many ways, men's and women's health care is the same'many medications for HIV and related conditions have the same physiological effect on both sexes. But access to treatment and the social conditions that contribute to rates of infection are different for women than they are for men. And some of the reasons for the discrepancies are only now coming into focus. Factors like pregnancy affect whether women can take certain kinds of treatments for HIV. Taking care of children and access to transportation have a disproportionate effect on whether HIV-positive women can visit the doctor. Similarly, women's ability to prevent infection is at least partly determined by their socioeconomic status and racial background, as evidenced by the fact that rates of infection for black women in the United States are a staggering 15 to 20 times higher than those for white women. To date, men's access to treatment and care has been studied far more frequently than has women's. But new approaches to treatment for HIV and AIDS are taking special note of women's needs. The results of recent studies are now shedding new light on the need for women-specific approaches to preventing infection. Advocates and researchers alike are optimistic in view of a recent antiretroviral microbicide gel trial. The study of 889 sexually active women aged 18-40, conducted by the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA), showed a 39% percent decrease overall in the likelihood of HIV infection for those who used the vaginal microbicide; those who used the gel most regularly (at least 80% of the time) cut their odds of infection by 54%. This marked the first successful trial of a microbicide. The microbicide's active agent, tenofovir, has been an effective oral antiretroviral medication since it was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2001, but its use in a topical gel form to prevent infection is a new development. The gel is designed to protect against infection by preventing the virus from reproducing itself inside susceptible cells. Tenofovir gel is rapidly absorbed by cells in the genital tract, where exposure to the virus occurs, and stays there. The CAPRISA microbicide trial results are 'an exciting step forward for HIV prevention,' says Kevin Fenton, MD, Ph.D., and director of the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. 'While these findings will need to be confirmed by other research to meet requirements for licensure by FDA and other regulatory bodies throughout the world,' he adds, 'they suggest that we could soon have a new method to help reduce the heavy toll of HIV among women around the world.' Community and world health activists are heartened because this gel gives women more control than other prevention methods. It can be difficult for women to persuade their partners to use condoms or remain monogamous. The results of a further tenofovir gel trial, involving several African countries, are expected in 2013. But Alan McCord, spokesman for San Francisco'based AIDS organization Project Inform, said American researchers won't wait to probe for stateside benefits that address the needs of American women and men. U.S. researchers are also focusing on women who are already HIV-positive. The GRACE (Gender, Race, and Clinical Experience) study looked at North American women who have received treatment for HIV to see if they responded differently to their meds than men do. This study, the largest of its kind to date, took special interest in women of color, a group traditionally underrepresented in clinical studies. The results, published in 2010, included revelations about the ways in which women maintain their levels of treatment'and how future trials can attract women. 'GRACE has the potential to shape how future HIV studies should be conducted because it addressed head-on the social and economic barriers, such as lack of support, stigma, availability of child care, and lack of transportation, which often have prevented women and people of color from participating in HIV clinical studies and remaining in care,' says Kathleen Squires, MD, director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Thomas Jefferson University and primary investigator in the GRACE study. Importantly, the results of the GRACE research suggest that when women, particularly women of color, get the help and support they need, they are more likely to connect with and stay in treatment. Women can get this assistance by seeking encouragement from friends and family, joining HIV/AIDS community groups, and sharing stories and concerns with other women who have HIV or AIDS. Brian Risley, who manages the treatment education program at AIDS Project Los Angeles, says study leaders increased participants' access to transportation, child care, and counseling with both health professionals and other HIV-positive women. These factors, he said, made it easier to recruit and retain participants, and provided a benchmark for future studies. Risley adds that American women diagnosed with HIV can look forward to a new drug called rilpivirine, which is close to FDA approval. Rilpivirine will be used in combination with two other medications in a once-per-day pill. Risley says it has fewer side effects than previous generations of nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, and in clinical trials, the drug has shown no adverse effects on fetal development. This makes it a better therapy for pregnant women than previous drug combinations that include the NNRTI Sustiva (efavirenz), which is not recommended for use during pregnancy. Risley is cautiously optimistic about treatment advances, noting the research and regulatory approvals required before new drugs are market-ready. Governmental bodies too are taking an interest in the racial and gender disparities that affect health. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' Office of Minority Health last fall announced $16.2 million in grants to support efforts to eradicate disparities in health care among ethnic minorities. The money will go to states, territories, colleges and universities, organizations that serve Native American tribes, and community groups. Some $2.8 million of that money will go to social support groups that address minority families living with HIV or at high risk of infection, including those dealing with incarceration and substance abuse. Another $1.15 million was awarded to the Minority Community HIV/AIDS Partnership to reduce risky behavior among minority college students. 'We're living in extraordinary times with many opportunities to improve the nation's health and ultimately achieve health equity,' said Howard K. Koh, MD, MPH, assistant secretary for health, in announcing the grants. 'These grants will provide much needed support for a variety of programs that will improve health outcomes among minorities.'

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

“So much life to live”: Eric Nieves on thriving with HIV

September 03 2025 11:37 AM

The Talk: Beyond the exam room

August 13 2025 3:15 PM

Messenger RNA could be the key to an HIV vaccine — but government cuts pose a threat

August 20 2025 8:02 AM

It’s National PrEP Day! Learn the latest about HIV prevention

October 10 2025 9:00 AM

Amazing People of 2025: Javier Muñoz

October 17 2025 7:35 PM

The lab coat just got queer

August 21 2025 10:00 AM

The Talk: Owning your voice

August 25 2025 8:16 PM

“I am the steward of my ship”: John Gibson rewrites his HIV narrative

September 16 2025 2:56 PM

Plus: Featured Video

Latest Stories

HIV-positive men stage 'Kiss-In' protest at U.S.-Mexico border

December 01 2025 12:56 PM

What the AIDS crisis stole from Black gay men

December 01 2025 6:00 AM

The Talk: Navigating your treatment

August 01 2025 6:02 PM

The Talk: Starting the conversation

July 25 2025 4:47 PM

Thanks to U=U, HIV-positive people can live long, happy, healthy lives

July 25 2025 2:37 PM

How the Black AIDS Institute continues to fill in the gaps

July 25 2025 1:06 PM

“I felt like a butterfly”: Niko Flowers on reclaiming life with HIV

July 23 2025 12:22 PM

Dancer. Healer. Survivor. DéShaun Armbrister is all of the above

July 02 2025 8:23 PM

BREAKING: Supreme Court rules to save free access to preventive care, including PrEP

June 27 2025 10:32 AM

1985: the year the AIDS crisis finally broke through the silence

June 26 2025 11:24 AM

VIDEO: A man living with HIV discusses his journey to fatherhood

June 10 2025 4:58 PM

Trump admin guts $258 million in funding for HIV vaccine research

June 03 2025 3:47 PM

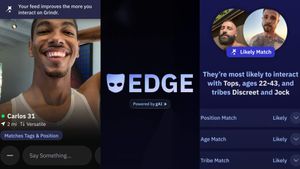

Grindr is reminding us why jockstraps are so sexy and iconic

May 02 2025 5:36 PM

HRC holds 'die-in' to protest Trump health care cuts

April 28 2025 2:11 PM

Two right-wing Supreme Court justices signal they may uphold access to PrEP and more

April 21 2025 4:10 PM

500,000 Children at Risk: PEPFAR Funding Crisis

April 08 2025 3:51 PM