Editor's Note: Samuel G. Freedman and Kerry Donahue, the Columbia Journalism school professors who wrote Dying Words, will be signing copies Wednesday February 3rd at [Words] bookstore in Maplewood, N.J.

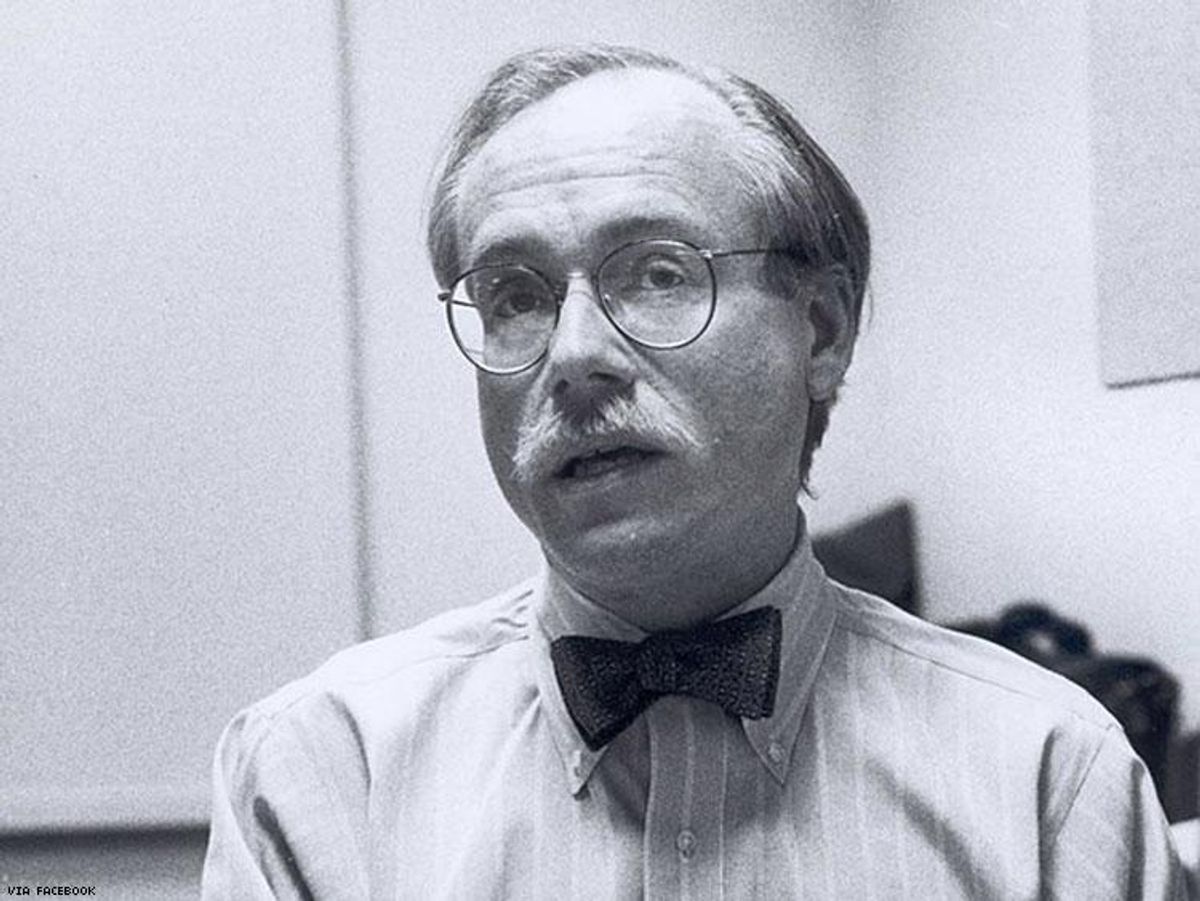

In an age when The New York Times publishes same-sex wedding announcements, regularly covers LGBT issues, and ran editorials in favor of marriage equality; it can be hard to remember just how different The Times was before Jeff Schmalz. In fact, most people have forgotten — or never heard of — Schmalz, and don’t realize how much his journalism, his homosexuality, and his death to complications of AIDS not only altered the venerable publication but also transformed how Americans think about HIV and LGBT issues.

Now, 22 years after his death at age 39, Schmalz’s contributions are finally being given the recognition they deserve in a multimedia presentation, Dying Words: The AIDS Reporting of Jeffrey Schmalz and How It Transformed The New York Times, which consists of a radio documentary and a biographical book of the same title. (Read an exclusive excerpt from the book below.)

Schmalz began working at The Times as college student in the late 1970s. A naturally gifted journalist, Schmalz fell in love with the work, dropped out to pursue a full-time position, and quickly rose through the newspaper’s hierarchy — at least until he hit what one might call a pink ceiling. In those days, particularly under executive editor Abe Rosenthal, the Times' newsroom was a notoriously homophobic bullpen. Even though Schmalz played it straight at the office his career trajectory was inexplicably capped and it was widely believed that had something to do with his lack of heterosexual trappings (like a wife and kids).

After he suffered a seizure in the newsroom in late 1990, his co-workers learned Schmalz had an advanced case of HIV. At the time AIDS was so intractably tied to gay men that his medical condition basically outed him. But what could have ended his career instead revitalized it. Schmalz recovered well enough to return to work and he did so on a mission to see The Times cover an epidemic that was still raging through New York’s queer community but was increasingly impacting other populations as well. By telling his own story and that of others, Schmalz began humanizing people living with HIV, destigmatizing those suffering from AIDS complications; and changing The New York Times' coverage of LGBT issues.

Starting with excerpts from his coverage of the epidemic and original recordings of Schmalz’s interviews with Magic Johnson, Bill Clinton and others; the creative partnership behind Dying Words also interviewed numerous journalists (including Anna Quindlen), AIDS activists and historians.

The audio documentary, produced by Kerry Donahue and hosted in part by Rachel Maddow, aired on public radio stations around the country and is available as a podcast. The companion book is a biography that includes excerpts from Schmalz’s work and was put together by Samuel G. Freedman. An award-winning author, Freedman is a professor at Columbia University and a columnist for The New York Times who was mentored by Schmalz before the journalist’s untimely death.

In the following exclusive excerpt from the foreward, Freidman, shares why he felt compelled to memorialize Schmalz with Dying Words:

As the last day of my two-week stint approached, Jeff gave me a field assignment. I would cover the Gay Pride Parade. I understood his agenda right away. Already in my brief time on The Times, Jeff had told me he was gay, the first person in my life to make what was then a risky admission. Somehow, in spite of my overall ignorance, he’d sized me up as someone capable of being sensitized to the reality of gay existence and of doing some small part to personally improve The Times’ coverage of it.

Walking along the parade route in Greenwich Village, trawling for a vivid scene or pithy quote, I spotted a young man named Jeff Natter. We knew each other from high school in Highland Park, N.J.; a year younger than me, Natter had succeeded me as editor of the school paper. He had also been the unrequited crush of my sister’s best friend. I had heard that he was working as an actor, but now as I reintroduced myself, he stood along Fifth Avenue wearing a hat emblazoned with the motto, “An Army of Lovers Can Not Fail.” I put that detail, and Jeff Natter’s name, in my article. He called me a few days later to say that, through the vehicle of The New York Times, he had come out to his parents. It occurred to me that in some sense I was outing Jeff Schmalz, as well — not in the sense of revealing the gay identity that he kept secret from his newsroom superiors but in the sense of doing some small good deed on behalf of tolerance in a largely intolerant time and place. Jeff burned for The Times to cover gay people and issues in a way that wasn’t exotic or judgmental, and he knew the newsroom politics well enough to recognize that such change would not happen easily.

Young, straight, sympathetic reporters like me were Jeff’s stealthy emissaries. After all, these were the days when official Times style forbade using the word “gay” except as part of a direct quote. The only acceptable term otherwise was “homosexual,” so chilly and clinical and alien. (Indeed, the headline that editors put on my story was “Pride and Joy at Homosexual Parade.”) I was just beginning to grasp the fear that many gay and lesbian journalists on The Times felt, a force that kept many in the closet and compelled several into paper marriages for the sake of their careers. Jeff must have first told me he was gay during one of our periodic working lunches. I can’t remember the exact time and place, or the precise words he used. But I remember his tone: calm, confident, matter-of-fact. Nothing had prepared me for the liberating ordinariness of his disclosure. My greatest mentor, a high school English teacher named Robert W. Stevens, had been a gay man driven into alcoholism by the pressure of being closeted in our small New Jersey town. When a college classmate of mine in the late 1970s confided to a group of friends that he had a gay brother, we took the news with a somber hush, as if to commiserate over a birth defect or deformity. And yet I considered myself an enlightened, liberal guy. Then, not so many years later, here was Jeff Schmalz steering my path at The Times.

If I had done well on an assignment, the phone rang for me in the Connecticut bureau, and Jeff would crisply say, “Hey, Scoop.” Jeff taught me that when I had intrinsically dramatic material I should keep my tone sober and subdued — “dead-away” was his phrase for it. He policed my copy to ensure that my own biases never showed through. “Without fear or favor” was The Times’ mantra; “straight down the middle” was Jeff’s mandate to me. And when I faltered—I can recall one particular article about a nuclear-freeze referendum in a Connecticut town – then the phone rang in the bureau with a different greeting. “When I read this story,” Jeff would say icily, “I know exactly what Sam Freedman thinks.” I would rewrite as quickly as possibly to regain Jeff’s approval. In some disconcerting ways, too, Jeff struck me as a pure product of The Times, a company man. In one of my first feature stories for the paper, about a hockey league for investment bankers and corporate lawyers in the tony suburb of New Canaan, I described a player changing out of his Paul Stewart shirt. “If you’re going to write for The New York Times,” Jeff told me with both levity and edge as he edited the piece, “you’re going to have to know how to spell Paul Stuart.”

A few months later, during a worrisome dry spell for me, Jeff assigned me to profile the former Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart on his return to his alma mater, Yale University. The article got big, splashy display, and I was grateful and relieved. I told Jeff as much during a subsequent lunch. But I also told him that there were plenty of people who went to public universities like Rutgers and UConn who were also Times readers, and stories about those schools also deserved attention, too. Jeff was unswayed. “When you read The New York Times,” he replied, “you expect to see a Tiffany’s ad and you expect to see a story about Yale.” Jeff’s lessons and advocacy ultimately brought me such visibility within The Times that I was plucked from Connecticut to cover the Broadway theater beat, a plum assignment. I wound up renting an apartment on the Upper West Side a few blocks from Jeff’s, so I saw him more both at work and outside the office. In our conversations, he offered me a window into a gay life that was neither tormented nor apologetic. When we had dinner after deadline one night at a Theater District bar Jeff favored, he flirted with the host right in front of me. He talked about the gay clubs he frequented, the way the dance floor lit up when all the chorus boys showed up after their Broadway shows. He even joked about his taste in men. “Twinkies,” he explained. “Young, blond, and dumb.” Jeff also confided an unexpected bit of self-doubt to me. He wanted to move into reporting from editing, and he worried aloud that he had so thoroughly mastered the quintessential New York Times story that he would never be able to break out of the formula. He would never have a voice of his own.

Here was another way of being a company man; here was another sort of being closeted. And I had to admit Jeff’s fears were well founded. When he began covering Connecticut in 1985, taking over what had been my beat, his articles seemed to me flawlessly constructed, impeccably reported, and yet ineffably mechanical. On a day-to-day basis, our paths diverged in 1987, when I left The Times to start writing books. Jeff was rising up the ladder to become bureau chief in Albany and then Miami. From afar, I followed his in-print feud with Governor Mario Cuomo, which started to loosen up something in Jeff’s prose. He was brought back to New York as deputy national editor, a sure sign he was on the trajectory to become one of the top editors on the paper. Then, in December 1990, I heard that Jeff had collapsed in the newsroom. Soon after, I learned that he had been diagnosed with AIDS. Remarkably, in that era before drug cocktails to manage the disease, Jeff recovered enough to return to work. And during the last year of his life, he took on the AIDS beat, finding his own voice after years of enabling the voices of reporters whom he mentored.

His profiles of basketball star Magic Johnson and activists Mary Fisher and Tom Stoddard, among many other people with HIV or AIDS, were filled with not only Jeff’s characteristic intelligence but an empathy and heart that were new in his copy. The disease that would kill Jeff cracked his soul wide open; his murderer provoked his greatest work. The last time I saw Jeff was in the autumn of 1993. He lay dazed and mute in his bedroom, far gone with AIDS. On his nightstand, I saw the paperback book he’d evidently been reading, Of Mice and Men. Something about Steinbeck reminded me of another detail from my conversations with Jeff. For all of his Manhattan panache, the crisply pressed trousers and shirt, the impeccable navy blazer, he spoke tenderly about having grown up in a small Pennsylvania town.

For recreation, his mother sometimes took him to watch the volunteer firefighters battling a blaze. Someday, Jeff told me, he wanted to write a novel about all that. Jeff died on November 6, 1993, at the age of 39. On a strangely glistening night several weeks later, I went to his favorite restaurant, Chanterelle, for a private memorial service that somehow, in an unforced way, became a festive celebration of his life. I knew from Jeff that his sister, Wendy, his only sibling, was a literary agent. I introduced myself to her that night, and I told her how honored I was to have been invited. I asked her how she had chosen the guests. “This was supposed to be Jeff’s 40th birthday party,” she explained. “He’d made up the list.”

Death was Jeff’s final lesson to me. Just as he was the first openly gay man I knew, he was the first person I knew to die of AIDS. In the years since then, his absence has harrowed me. I could not separate the upward arc of my writing career from the ways Jeff had elevated my abilities and negotiated my way through the labyrinth of Times newsroom politics, which had ruined people far more talented than me. For lack of a better term, I felt survivor guilt. And beyond it, I grieved that as the years passed, fewer people would remember who Jeff Schmalz was and what tremendous work he had done. Indeed, one evening nearly 20 years after Jeff’s death, my fiancée and I were having dinner with another couple — she a screenwriter, he a former magazine journalist now working on a cable series about journalism. The conversation turned to New York State’s recent legalization of same-sex marriage, a stance vociferously endorsed by The New York Times.

I mentioned how remarkable it was to me, having lived through such a homophobic period on the paper, to see The Times become a champion of gay rights. Then I found myself talking about Jeff and his AIDS articles, fully expecting that my friends would be familiar with him and them. But they drew a blank. That blank, of course, made sad sense. Jeff had been dead for a generation. Newspaper writing is evanescent, as perishable as the paper it is printed upon. Still, I could not believe that people who would know the names and work of Randy Shilts, Larry Kramer, Tony Kushner, Terrence McNally, Michelangelo Signorile, Andrew Sullivan — those artists and journalists who bore witness to the AIDS plague — could not know of Jeff Schmalz. It felt like a moral duty for me to do something to rescue Jeff from obscurity.

Those friends at dinner suggested a film, but I am no filmmaker. They suggested writing a biography, but I believed Jeff had left his own written record. As months passed, what came to me was the sound of voices—the voices of those who had known and worked with Jeff, the voices of those whom he had interviewed, the voice of Jeff himself. The story of Jeff Schmalz, it seemed to me, wanted to be a radio documentary. And in book form it wanted to be an oral history. I went to see Wendy Schmalz Wilde, to ask for her blessing. She gave me that, and she gave me more: a set of micro-cassettes on which Jeff had recorded his AIDS interviews. I also went to see Arthur Sulzberger, Jr., Jeff’s friend and the publisher of The New York Times. I sought both institutional and personal support—not because the documentary and oral history will be authorized, sanitized accounts of Jeff’s years at The Times, but precisely because the newspaper must be shown with its flaws in how it reported on gay issues and how it treated its own gay staff members.

Although I continue to maintain a formal association with The New York Times, writing a monthly column on religion, the content of this book and the companion radio documentary were produced by me and my collaborator, Kerry Donahue, with complete editorial independence. We began with a clear, linear goal: to recount Jeff Schmalz’s life and work in his years on The Times. As we proceeded, though, it soon grew evident that Jeff’s story unfolded into larger stories: what it meant to grow up gay amid anti-gay bigotry; how wrenching it was to come out, for fear of being scorned by friends and family and ostracized or fired by employers; the blind spot in the conscience of the nation’s most powerful and respected newspaper; the sheer terror and rampant death experienced by people with HIV or AIDS in the years before drug cocktails made them endurable diseases. There can be no gainsaying the bleakness of disease, death, self-denial, and bigotry. And yet, finally, Jeff’s experience tells us something essential about the positive changes in American society, including The New York Times, in the acceptance of its LGBT citizens over the past generation. Jeff Schmalz did not live to see those changes, but his life and work helped to make them possible.

Dying Words: The AIDS Reporting of Jeffrey Schmalz and How It Transformed The New York Times is available through the City University of New York (CUNY) Journalism Press.