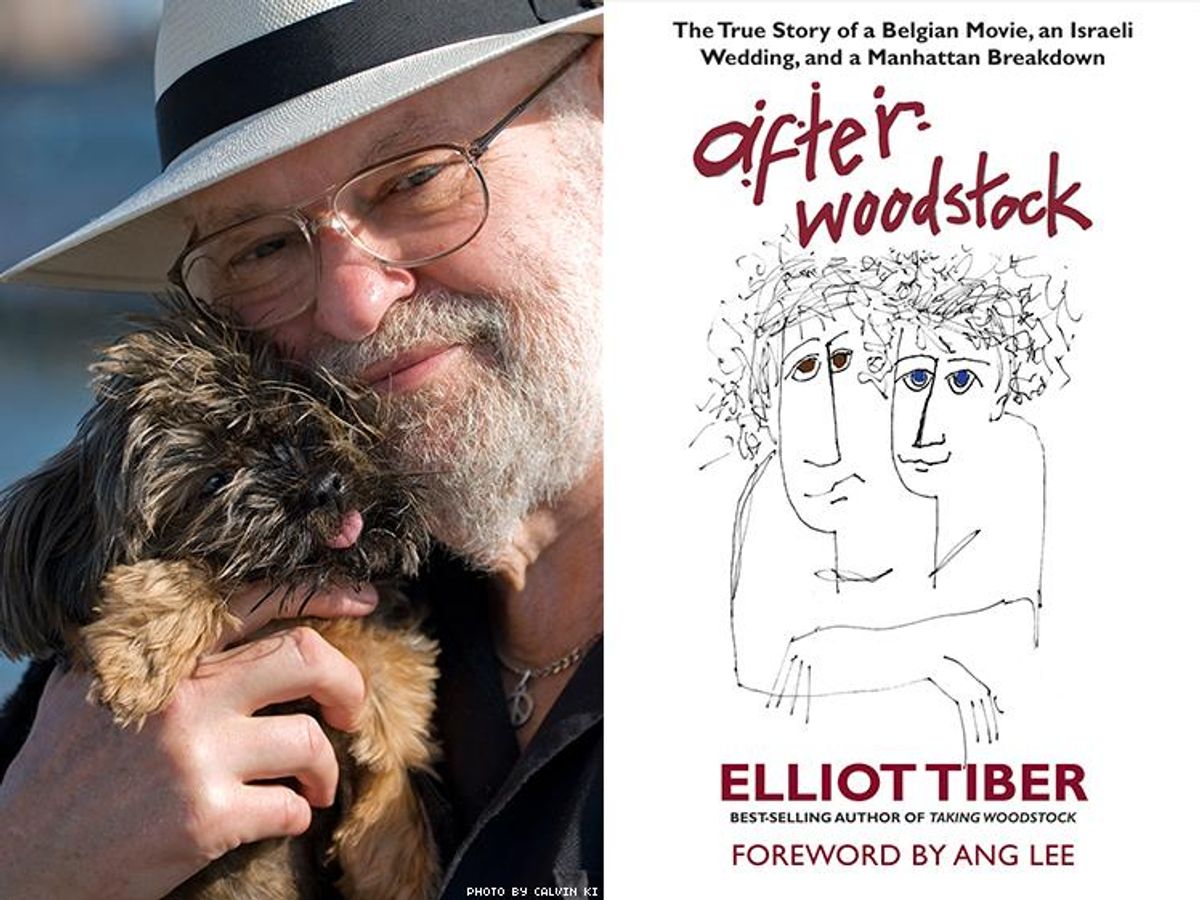

During the summer of ’69, Elliot Tiber helped start the gay liberation movement and saved the Woodstock Festival from cancellation. His best selling memoir, Taking Woodstock became a hit movie by Ang Lee. But some of Tiber's most memorable moment occurred after those legendary events, and you'll find them in After Woodstock: The True Story of a Belgian Movie, an Israeli Wedding, & a Manhattan Breakdown.

One of the new memoir's most compelling — and heart-wrenching — chapters is "The Gay Plague," about the early '80s when AIDS ravaged New York City's gay community. Plus magazine is proud to share an excerpt of that chapter below:

***

“Hey, did you hear about Paul?”

I looked up casually from my classroom desk at the New School that spring semester of 1983, and overheard two of my students talking to each other as they filed out of the room.

“Paul? What about him?”one said.

“Well, I hear he’s got that new gay disease people are talking about. You know, that thing they’re calling the ‘gay cancer.’”

“Holy shit. Really? Wonder how he got it!”

“How do you think, dickhead? From being a f****t, that’s how.”

“No wonder he’s been missing classes. Hey, do you think only fags can get it?”

“I hope so. I sure as fuck don’t want to catch it from some homo queer. C’mon, let’s get out of here.”

I learned two things in that moment. First, there were still a lot of people who hated others for being gay. And second, the stories I had increasingly heard and read about a terrible illness that was killing gay men had now reached my classroom.

By 1983, it seemed like gay men in New York were dying in unprecedented numbers. My lover André and I were shocked as we started to hear that more and more friends of ours — gay men we knew from the clubs and colleagues in the arts community — were suddenly being hospitalized. The pain and suffering they endured was horrible; it seemed that death was their only reprieve. It was the worst nightmare imaginable, a nightmare that didn’t end. It almost felt as if we were being punished for letting down our guards a little. Just as things had started to get a little better for the gay community — just as we were beginning to gain some acceptance and have our rights acknowledged — this plague came and wiped out any sense of security we might have had. We realized that we and everyone we knew could very well get sick and die within a matter of weeks or even days.

The leather bars and the bath houses were the first to be closed by the department of health. Then, one after another, the sex clubs were shut down. The bars were nearly empty. Almost everyone we knew stopped having sex, terrified of catching the disease. For all the talk within the gay community, though, the public at large remained almost silent about the growing epidemic. At best, the situation was met with denial and resistance. At worst, gay people were shunned and blamed for bringing this new plague to the planet. And it wasn’t just the mainstream media that did us wrong. Elected officials from Mayor Koch to President Reagan initially ignored our desperate pleas for action, refusing to even mention the gay cancer in public.

Then there were the hospital visits, and the funerals. It was all I could do to keep waking up every day — so many of our friends and colleagues were dying. There was Bobby, our favorite waiter at our favorite Italian restaurant. Wayne, who owned a hardware store in Chelsea, and his boyfriend Charlie, who was an accountant by day and an inspired jazz guitarist by night — they died within four months of each other. Angelo and David were Juilliard-trained dancers who tried one night back in 1981 to teach André and me how to tap-dance, with hilariously bad results. Angelo died from the illness on Christmas Eve 1984, and a broken-hearted David took a fatal overdose of sleeping pills the following Valentine’s Day.

Not all of the men who died were from New York. Jackie had been born and raised in Texas during the Dust Bowl years. He had gone on to work as a stuntman on various Hollywood movies for two decades, before a back injury forced him to retire. Jackie had worked mostly in low-budget Westerns; his natural tan guaranteed him plentiful work as an “Indian.” Jackie was one of the most captivating men I had ever met. He brought to the East Coast some fairly wild stories about his time in Hollywood. He once told us how legendary Western movie star John Wayne called him into his trailer during the making of a film. When Jackie got there, Wayne chased him around his dressing room wearing only a towel knotted at the hip, all the while playfully shouting “Coo-chee coo-chee coo, yuh sweet-ass Injun!”

He also talked about how he was almost cast as a Mexican bandit in Marlon Brando’s first and only directorial attempt, One-Eyed Jacks. Jackie told us that he was passed over for the part, though, because he wouldn’t let Brando masturbate him at the end of the closed-door audition. After the film’s release, Jackie would always refer to that movie as “The One-Eyed Jack-off.”

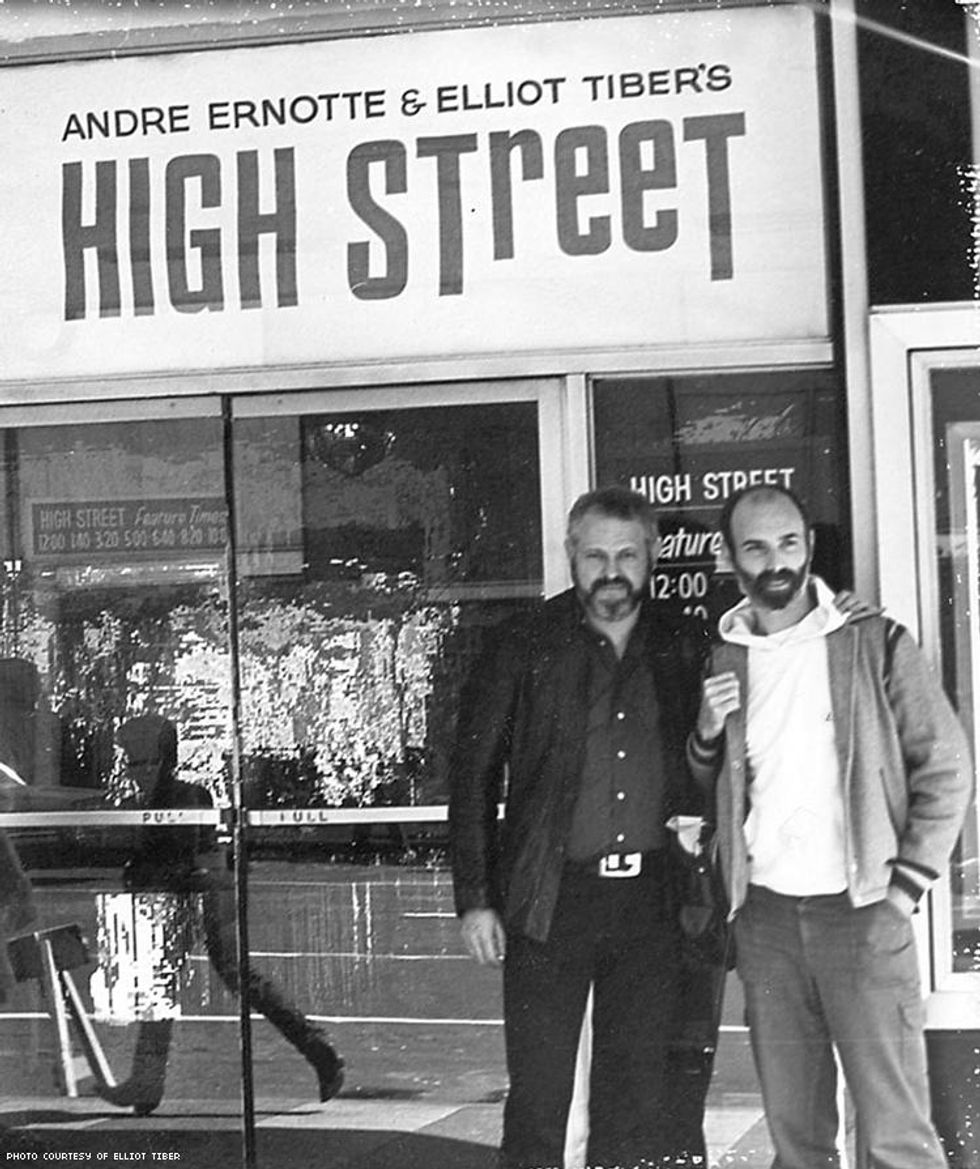

Elliot with Andre

I told him about my brief time trying to break into Hollywood as a production designer, and how I failed so miserably at it. Placing his big arm across my shoulders, he looked me right in the eyes and said in his easy Texan drawl, “Elliot, there ain’t nothin’ but a whole world of hurt out there in them goddamn Tinseltown hills. You ask me, I say you done a helluva sight better for yourself pullin’ on out of there when you did. Set your sights on other horizons, baby. Take it from me, the last of the Hollywood Mohicans.” Jackie had a sweet and gentle heart to him, and he forever changed my previously wary view of people from Texas. They weren’t all like that mean-eyed, trigger-happy ranger who had pulled me over on that desolate Texas highway years before.

Jackie had been closeted during his early years, but came out in a big way after his injury forced him to quit doing stunt work. At forty-five, he moved to San Francisco and fell madly in love with Martin, a gifted poet twenty years younger. When André and I first met them, Jackie was driving a taxi cab and Martin was working as a creative writing teacher for the New School, while also finishing the third of three wonderful novels that were never fated to be published. It was Martin who got sick first. He was admitted to a hospital within a month of his first lesions and dead from the disease less than three weeks after that. Jackie sat and held Martin’s slowly trembling hands during his final hours of painful suffering. When he was told by the head nurse that he was not entitled to be by Martin’s side because he was not a family member, Jackie got up from the hospital room chair and headed for Texas, driving the taxi cab that still belonged to his employers. We never heard from Jackie again, but we did catch a rumor that he had been found dead at the wheel of his taxi after driving it into a ravine somewhere out in the lonely hills of Maryland. A fitting way for a stuntman to die.

Vincent, Michael, Joey, Sidney, Tommy, Alan — all of them wonderful guys, and all of them dead within weeks of getting sick. Whenever we found out a friend was sick and in the hospital, we would go to visit. The lifeless men we saw in those steel beds might as well have been strangers to us. We would say their names, tell them we were there with them, tell them we loved them. Sometimes, they would open their sunken eyes and smile weakly when we spoke. More often, they just lay there like gaunt zombies, their skin riddled with dark lesions, as the hospital nurses tended to them wearing gloves and surgical masks and hoping like everyone else that they wouldn’t catch the disease. As time went on, we’d only hear about a friend’s illness after he had already succumbed to it. Far from being cruel, this allowed the one who was dying a final dignity — many wanted their friends and lovers to remember them as they were, not as they had become.

Over the next two and a half years, we must have attended over thirty funerals — nearly one each month. And with each funeral, attendance seemed to shrink. Once it was known that someone had died from this gay cancer, only a handful of family members, if any, would show up, and perhaps a few close gay friends. Straight people shunned these funerals, and many used the situation to fuel existing prejudices against gays. Terrible as it might seem, we felt almost a sense of relief once we began to get reports that heterosexual men and women were getting the disease as well. The involvement of straight men and women allowed us to hope that there might finally be formal acknowledgment of the epidemic by the White House. But we also worried that we’d be blamed even more vehemently for the fact that straight folks were getting sick. It was starting to feel a little scary again, walking the streets of Manhattan as a gay man.

In early August 1985, only a few weeks after America learned that beloved actor Rock Hudson had AIDS, we went to another funeral. This time, we were paying our respects to a twenty-one-year-old named Daniel, whom André had once directed in a play at Columbia University. André had turned forty-two in June, and it was upsetting for him to see a young man half his age lying there dead in a casket. We were all brought to tears when we realized that not one member of his entire family was there at the funeral home. Daniel’s father had apparently paid for all the arrangements and flowers had been sent by aunts and uncles and cousins, but this young boy’s mother and father were nowhere to be found. It was the saddest funeral that André and I were to witness in those terrible years.

As we left the funeral home, one of the other mourners, a friend of Daniel’s from school, shared a story about how he and his friend were thrown out of a local bar by two drunk straight guys. They’d been told, “God is killing all you f****ts because it’s what you deserve. You’re all gonna die, you fuckin’ queers! Go home and fuckin’ die!”

This ugliness filled us with sorrow and rage. André looked at the man with tears in his eyes, and said, “Who are they to judge us? Who are they to say we should die?” We all nodded our heads in agreement, but there was nothing left to say.

As we made our way back home to our apartment, André stared straight ahead and didn’t say a word. About an hour later, with the silence standing like an invisible wall between us, I spoke up.

“What’s wrong, André? Tell me what it is. Whatever it is, I’m here. Let it out.”

He stood up from the couch, his eyes filled with tears. “Why do they hate us so much, Elliot?” he asked, still bothered by the people in the mourner’s story. “I am not some horrible monster. I am a good person, a kind man. I have love in my heart, but my heart is being broken by all this death and hatred. It makes me — I am so sad because I —”

Unable to finish his remarks, he fell to his knees and broke down in front of me, his sobs growing louder and louder. I knelt gently next to André, and draped my arms over him. Our embrace threw open the floodgates, as we began to weep together. André’s voice grew hoarse from crying. “André, it’s okay. It’s okay, babe,” I kept saying, trying to comfort and soothe him.

“I hear what people say about us. Maybe what they say is right, Elliot. Maybe this is some kind of a curse, some kind of plague meant to destroy us. Maybe there is something wrong with us. I do not understand. Why would God allow something like this to happen? Why allow so much misery and pain?

“Sometimes,” André continued, “I hate myself so much because I know that I am different. These people, they do not understand. I never chose to be the way that I am. When my father realized the way I was, he grew so distant; he shut me out of his life as if I were a stranger to him. I am his son, his only son. My mother and my sisters have always loved me, no matter what. But my father—in his eyes, it was as if I no longer truly existed. He never said a word, but I knew. I could never change who I am. But maybe that is why we are all dying now. I love my father. Why could he never love me?”

I could feel the depths of André’s anguish. I took a few deep breaths and tried my best to calm him down, or at least ease the pain that he was going through.

“Listen,” I said, “we have no idea why this thing is happening to us. You can blame a goddamn scientist who fucked up in a lab, or a sick sheep that passed it on to a horny herder, or the KKK. We don’t have any real idea why this is happening. All we know is that we don’t know.

“And hey,” I continued, “so you’ve never had a good relationship with your father. What about me with my mother? Imagine if you had to live with my mother every day when you were a kid? As a matter of fact,” I joked, “take my mother now — please!”

That got him laughing a bit, and he finally got a hold of himself.

“So sorry. I am so sorry, Elliot,” he said, as we held each other there near the foot of the couch. For the first time in a long time, there we were again — two lost souls, united in a world of madness and pain. I consoled him, telling him that everything would be alright. But the real truth was that I was as scared as everyone else. All I could do was to try to ensure our survival. And that was why I decided that neither of us would attend any more funerals of those who died from AIDS. André and I simply had no strength left to handle the heavy burden of loss that weighed so relentlessly upon our community.

That night, after André passed out with our beloved Yorkie terrier Shayna sleeping next to him, I wrote down the name of the young man whose funeral we had attended that day. It was the thirty-fourth name on the list of people we knew who had died over the past two and a half years. I brought the list into the kitchen, and there I took a match and set fire to it. I dropped the flaming pieces of paper into the sink, and then slowly doused the burnt offerings with water from the faucet.

***

ELLIOT TIBER is a best selling author and playwright. His memoir, After Woodstock: The True Story of a Belgian Movie, an Israeli Wedding, & a Manhattan Breakdown, from which this excerpt came, is available here.