Treatment GuideJust DiagnosedSex & DatingAfrican AmericanStigmaAsk the HIV DocPrEP En EspañolNewsVoicesPrint IssueVideoOut 100

CONTACTCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2026 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Every few months I have a patient who has just picked up HIV and is acutely seroconverting'what's called primary infection. Sometimes the patient comes in with a suspicious set of viral symptoms: fever, swollen glands, viral rash, etc. But sometimes the patient merely has a history of high-risk exposure and is asymptomatically seroconverting. When antibody tests come back positive, I do some counseling and reassure patients about the manageability of HIV in the 21st century; then I move on to a theoretical discussion. Should we start treatment right away? Various treatment guidelines around the world recommend waiting to start antiretrovirals until a CD4-cell count is, depending on location, below 200'350, or a viral load is above 55,000'100,000. It should typically take about 10 years before a patient's numbers reach those ranges. However, some decline more rapidly and could need treatment in three to five years. Others are slow progressors and might not need treatment for 12 to 15 years. About 1% are the long-term nonprogressors, who still have not needed treatment after more than 20 years of seropositivity. There is no way to initially tell who is going to be a rapid or a slow progressor. However, we do know that after the initial burst of HIV replication and rapid rise in viral load, the immune system will kick in and bring down the viral load. And after four to six months the viral load is at a steady state'the set point. The lower the set point, the longer the patient will go before needing treatment. But several questions arise: Would immediate suppression of that viral burst by a short course of antiretrovirals improve the chances of a low set point? If the antivirals were continued, would there be a better chance of eradication sometime in the future when new therapies become available? Is there harm in trying this? The answer to the first question is no. Although several years ago there was evidence that early treatment preserved HIV-specific immune responses, giving better viral control'that is, a low set point'long-term follow-up has shown that this benefit is not maintained. After being off treatment for one year, patients who received early treatment had viral loads and CD4 cells in the same ranges as patients who were not initially treated. Preserving future eradication potential is a more interesting question, though. There is no evidence that immediate treatment can prevent HIV infection of the resting CD4-cell reservoir, which appears to be infected within 48 hours of the first symptoms of HIV. However, it does appear that early treatment can reduce the size of the infected reservoir. This might be reflected in one study that showed fewer blips in viral load measurements in patients who had early treatment when compared to those who started treatment later. Another study used an ultrasensitive viral load test to compare early versus late treatment. Viral loads of less than three were found among early treaters, compared to none in that range in the late treaters. What we don't know is whether these indicators of profound viral suppression translate into better long-term viral control. Early treatment does preserve a more homogeneous viral population. This happens because HIV continually mutates as it replicates. So the longer you wait to suppress HIV, the more variation there is in the HIV that is created. Theoretically'and I emphasize theoretically'future types of vaccine or antibody treatments might work better on a homogeneous population of HIV. But there is a downside to this particular approach. Because viral loads are often very high in primary infection, there is some concern about provoking antiretroviral resistance with one short course of treatment. But the long-term side effects, such as lipodystrophy, would not be an issue in that case. This does become an issue, of course, if early treatment is continued in the hope of increasing future eradication. As is so often the case in HIV medicine, there is no clear answer. The best recommendation is to refer acute seroconverters to any studies of early treatment strategies that are available in your area. If we can get some answers from these studies, then we won't need another one of these 'what if' discussions. Bowers is board-certified in family practice and is a senior partner with Pacific Oaks Medical Group, one of the largest U.S. practices devoted to HIV care. E-mail him at dan@hivplusmag.com.

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

“So much life to live”: Eric Nieves on thriving with HIV

September 03 2025 11:37 AM

The Talk: Beyond the exam room

August 13 2025 3:15 PM

Messenger RNA could be the key to an HIV vaccine — but government cuts pose a threat

August 20 2025 8:02 AM

It’s National PrEP Day! Learn the latest about HIV prevention

October 10 2025 9:00 AM

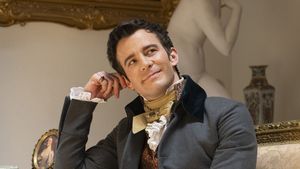

Amazing People of 2025: Javier Muñoz

October 17 2025 7:35 PM

The lab coat just got queer

August 21 2025 10:00 AM

The Talk: Owning your voice

August 25 2025 8:16 PM

“I am the steward of my ship”: John Gibson rewrites his HIV narrative

September 16 2025 2:56 PM

Plus: Featured Video

Latest Stories

HIV-positive men stage 'Kiss-In' protest at U.S.-Mexico border

December 01 2025 12:56 PM

What the AIDS crisis stole from Black gay men

December 01 2025 6:00 AM

The Talk: Navigating your treatment

August 01 2025 6:02 PM

The Talk: Starting the conversation

July 25 2025 4:47 PM

Thanks to U=U, HIV-positive people can live long, happy, healthy lives

July 25 2025 2:37 PM

How the Black AIDS Institute continues to fill in the gaps

July 25 2025 1:06 PM

“I felt like a butterfly”: Niko Flowers on reclaiming life with HIV

July 23 2025 12:22 PM

Dancer. Healer. Survivor. DéShaun Armbrister is all of the above

July 02 2025 8:23 PM

BREAKING: Supreme Court rules to save free access to preventive care, including PrEP

June 27 2025 10:32 AM

1985: the year the AIDS crisis finally broke through the silence

June 26 2025 11:24 AM

VIDEO: A man living with HIV discusses his journey to fatherhood

June 10 2025 4:58 PM

Trump admin guts $258 million in funding for HIV vaccine research

June 03 2025 3:47 PM

Grindr is reminding us why jockstraps are so sexy and iconic

May 02 2025 5:36 PM

HRC holds 'die-in' to protest Trump health care cuts

April 28 2025 2:11 PM

Two right-wing Supreme Court justices signal they may uphold access to PrEP and more

April 21 2025 4:10 PM

500,000 Children at Risk: PEPFAR Funding Crisis

April 08 2025 3:51 PM

Trending stories

Recommended Stories for You