Stigma

Book Chronicles HIV in Botswana

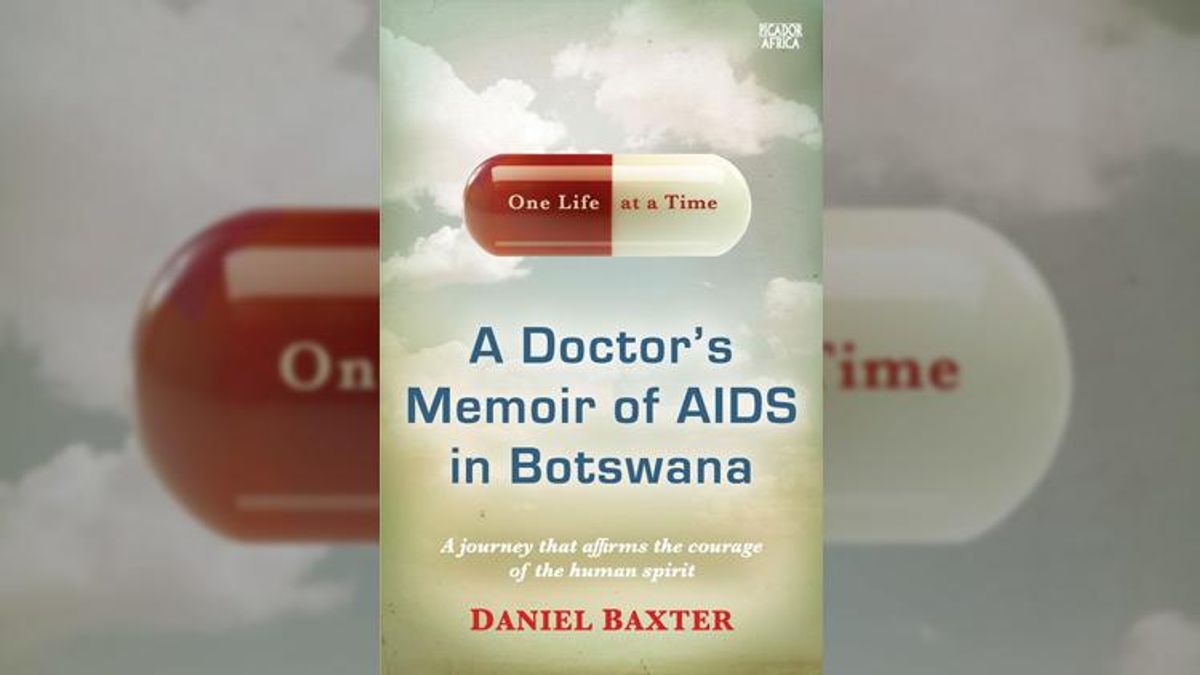

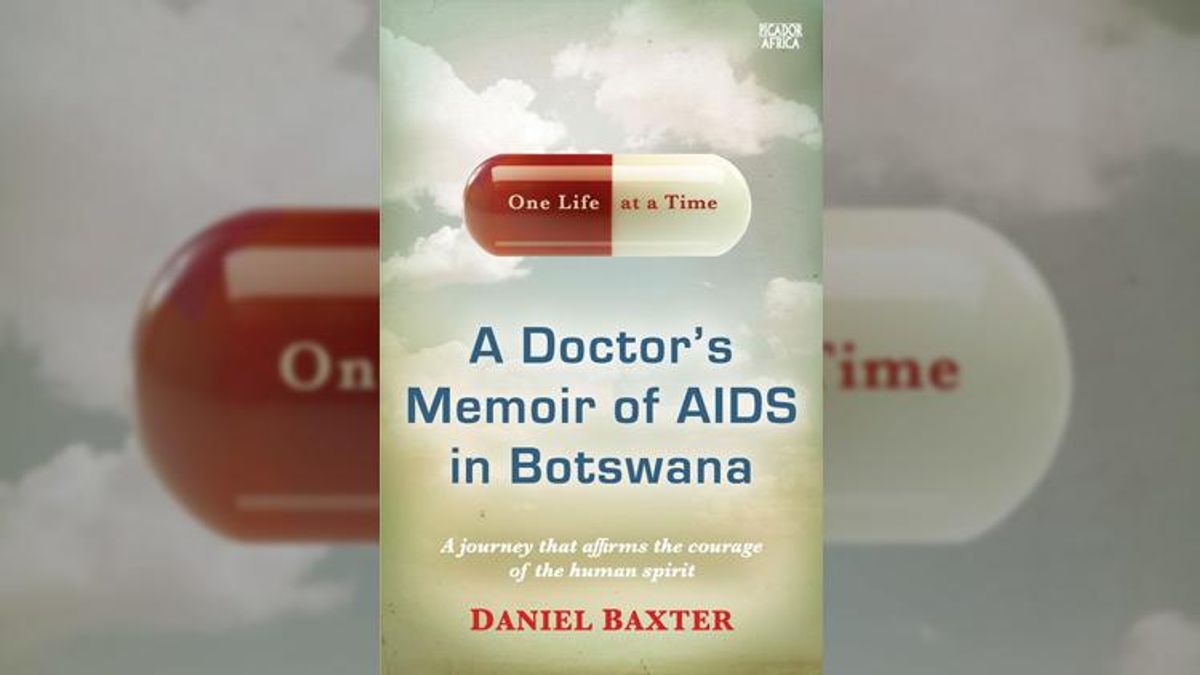

One Life at a Time: An American Doctor’s Memoir of AIDS in Botswana tells a tale of what one American doctor encountered as the epidemic tore through the African nation.

August 31 2018 8:09 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

One Life at a Time: An American Doctor’s Memoir of AIDS in Botswana tells a tale of what one American doctor encountered as the epidemic tore through the African nation.

Nothing — not even in his years in New York City's AIDS wards during the early days of the epidemic — could have prepared Dr. Daniel J. Baxter for the horrors and the triumphs that he would encounter while directing patient care in Botswana. When he first stepped foot in Botswana in 2002, up to one out of every four Batswana was exposed to HIV, and nearly half of all pregnant women that checked into Francistown's main hospital were HIV-positive.

Dr. Baxter is currently the clinical coordinator at the William F. Ryan Community Center in New York City. His new novel, One Life at a Time: An American Doctor’s Memoir of AIDS in Botswana, covers over eight years of the epidemic in Africa.

Baxter was stationed in Botswana to direct patient care for the African Comprehensive HIV/AIDS Partnerships (ACHAP). ACHAP is a reality, thanks to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Merck Pharmaceuticals. Merck covered the treatment and Bill Gates covered other costs.

While many blamed HIV on the gay community in the early days in America, in Botswana, HIV was sometimes blamed on a witch doctor curse.

Most now accept that HIV originated in West Central Africa, and Dr. Baxter believes that the main reasons for the initial spread of HIV in the area were a combination of sexual practices, increased industrialization and transportation, highways, and an increase in the number of sex workers. Poverty was another major factor.

Moving to Botswana, as you can imagine, was a slight change of scenery. “I really had no idea what Botswana was like, other than what I had read online,” Dr. Baxter told Plus. “A large portion of it is taken up by the Kalahari Desert, which really isn’t a desert in the sense of sand dunes, lots of bush and brush and wild animals, including lions in the Kalahari. The northern part of Botswana is more verdant with the Okavango River and its tributaries, and then you have wild animals, giraffes, elephants, lions and cheetah and so forth.”

Some patients didn't understand the commitment required of ARTs and the dangers that existed. Others would be in the later stages of the disease in hospices. “I found solace in the time and space and also in the majestic clouds in Botswana,” he said.

Many of his patients refused to take HIV tests, out of shame or from dangerous, realistic fears. Effective ARTs were available to some by the time he was in Botswana. Some firstline drug regimens consisted of combivir and efavirenz, which some regarded as magical, and the effects against HIV are indeed magical. Abortions were illegal, so HIV-positive women would be forced to find “back alley abortionists.” But through his work, he describes remarkably positive people, with wishes and dreams of their own.

Missed opportunities is a hard thing burden to bear. “We do know in South Africa, for example,” Dr. Baxter said, “the willful indifference of the President Thabo Mbeki in the early part of the century probably cost the lives of 300,000 South Africans. They could have been saved, had South Africa addressed it more directly.”

Dr. Baxter experienced a lot of avoidable problems in Africa. “Hatred, indifference and simply not caring have resulted in suffering,” he said. “And the suffering, as you may know, is not just physical, but [psychological] as well.”

Baxter is also author of The Least of my Brethren: A Doctor's Story of Hope and Miracles on an Inner-City AIDS Ward, an acclaimed book. In it, he describes the 17-bed AIDS ward at the Spellman Center for HIV Related Diseases at Saint Clares Hospital in Manhattan, with every sort of HIV victim you could imagine. “As you know, back in the late 1970s and early ‘80s, the gay community was in a state of terror because coming down with HIV back then meant you were gay, used drugs or both,” he explained. “I’ve always believe that history always gets it right in the long term. The history until the early 1980’s show that tens of thousands of lives were lost because people were afraid to come forward and be tested—and they didn’t because of the stigma and fear. [It’s difficult] to estimate the number of lives lost from the ignorance, hatred, and intolerance that HIV had back then.”

Thankfully, people living with HIV nowadays usually don't have to endure the horrors of the past with highly effective therapies with generally minimal toxicity and side effects. “There’s an awful lot of research being done in terms of finding a functional cure,” he said, “where people can be taken off of ARTs and perhaps even a cure itself. I don’t at this point, see some kind of Andromeda strain of a highly resistant HIV that drugs don’t treat. Not just in terms of treatment, but also in terms of prevention.”

Dr. Baxter's experiences in Botswana led him to return in 2013 to lecture.