Treatment GuideJust DiagnosedSex & DatingAfrican AmericanStigmaAsk the HIV DocPrEP En EspañolNewsVoicesPrint IssueVideoOut 100

CONTACTCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2026 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

For many of the world's women, condoms are the only method available, aside from lifelong abstinence, to avoid potential infection with HIV by the men they have sex with, says Robin Maguire of the U.S.-based Population Council. But, she warns, condoms come with impassable hurdles in many cultures. First, many women cannot insist that their husbands use them, and second, they must have sex whenever their spouses desire, even if their men have visited prostitutes or have had extramarital affairs. Yet another hurdle looms larger for some. Condoms also prevent pregnancy, and in many societies a woman's primary role'no matter the view of the Western world'is to bear children. 'These women would rather risk getting HIV than not getting pregnant,' notes Barbara Friedland, program manager at the Population Council. With an even partially effective HIV vaccine a decade or more away, according to experts, researchers are turning to a burgeoning field that offers hope in slowing HIV's merciless spread: microbicides. Depending on their method of action, microbicides'vaginal creams, gels, or foams that can destroy HIV or prevent it from infecting human cells'can allow a woman to protect herself against HIV and possibly still become pregnant. 'Basically, the failure to develop a vaccine has been seen as a wake-up call; we can't put all our eggs in one basket,' says Kathleen Morrow, Ph.D., an assistant professor for research at the Centers for Behavioral and Preventive Medicine at Brown University Medical School. 'We have to try other things, and microbicides are a very viable possibility.' Medical Discovery...Again Microbicides have been on the radar screen of many researchers since the late 1980s, says Zeda F. Rosenberg, head of the International Partnership for Microbicides. But with a desperate need for antiretroviral medications and with vaccine research receiving precedence as preventive medicine, microbicides for years took a back-burner position among research priorities'particularly at large pharmaceutical companies, where microbicide funds are still scarce. 'It's also not very sexy science,' says Polly Harrison, Ph.D., director of the Silver Spring, Md.'based Alliance for Microbicide Development, a six-year-old nonprofit advocacy group. 'If you say you want to make something that sounds like sunscreen for sex, people think, Is this science? I don't think so.' But as global infections continue to climb, now hovering near 5 million per year, more attention and money are slowly being directed to developing microbicides as defenses against HIV. In 1998, when the microbicide alliance was formed, only about $27.4 million was allocated by U.S. groups for microbicide research. Today, U.S. organizations like the Rockefeller Foundation, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and other agencies channel about $108.2 million to the effort, and that does not include international support, says Harrison. The boosted funding and dogged determination by microbicide advocates has paid off. More than 60 compounds are in development, and six candidates are in advanced human trials. Benefit of Diversity Rosenberg says microbicide products work in various ways, some serving also as contraceptives yet others virtually ignoring sperm. Some, like Savvy, currently in Phase III human trials, are called surfactants, which work as a sort of detergent that not only destroys HIV and some other sexually transmitted pathogens but also kills sperm. Others, like Carraguard, also in final human tests, prevent HIV from infecting human cells by coating the virus or the vaginal tissues to create an impenetrable barrier. Still others work by blocking key cellular receptors HIV latches onto; by lowering the pH of the vagina to create an inhospitable environment; or even in ways similar to anti-HIV drugs, by either preventing viral attachment or stopping replication in infected cells. This last approach is being studied at Gilead Sciences. Researchers there are looking at the use of tenofovir, an ingredient in Viread, the company's nucleotide analog, as a vaginal microbicide. Safety and tolerability tests have paved the way for a Phase II trial, set to begin in early 2005, says Jim Rooney, vice president of clinical research. Gilead's tenofovir-based product and others like it are being developed as once-daily applications to provide round-the-clock protection, even for women who must use compounds secretly if they do not wish their partners to know. Others are used just prior to sex, possibly even as lubricants or douches. It is unclear which of the four microbicides in final human tests will be the first to be cleared by the Food and Drug Administration'possibly by the end of the decade'and reach the consumer market. But whatever product initially arrives, it is not going to be a panacea, warns Gerianne Tringali DiPiano, founder, president, and CEO of women's health care pharmaceutical company Femme Pharma. None of the microbicides in advanced studies is 100% effective in blocking HIV transmission, she says, which leaves many to wonder why there is such a push to develop a product that does not offer surefire protection. Global Potential The answer to that question, say Morrow and other microbicide advocates, is that even a partially effective product can dramatically reduce the total number of HIV infections among the world's women. They commonly cite a study by researchers in London as proof of the potential impact of microbicides: Using mathematical models, scientists determined that if a microbicide is only 60% effective, is available to only 20% of women in 73 low-income countries and is used by those women only half the time they engage in condomless sex, the product would still prevent 2.5 million HIV infections over the course of three years. 'That's huge,' Morrow exclaims. 'We haven't heard a 'Wow!' message in the HIV field like that for a while.' The potential is even greater if microbicide makers combine products that have several different methods of action into a single gel, says Laneta Dorflinger, Ph.D., vice president of clinical research at Family Health International, which is involved with Phase III trials of Savvy. And when used with condoms'a scenario that all microbicide makers urge but recognize will not always be the case, particularly in situations where women are unable to negotiate condom use'the appeal of microbicides is even clearer. It is also possible that a microbicide will offer reverse sexual protection'allowing an HIV-positive woman to use the product to prevent transmitting the virus to her sex partners, Rosenberg adds. Getting to the Goal Much work still needs to be done, though, on the microbicides already in the pipeline. More research money is needed for every aspect of product development'particularly, Friedland notes, in laying the groundwork for the extremely large human studies in developing nations. And ancillary research is still needed to establish product formulations that have long shelf lives and can withstand extreme temperatures in developing countries, to identify behavioral issues or acceptability concerns that could hinder microbicide use, and to determine how to best market any emerging products both domestically and abroad. Even mass-producing enough of test compounds for human studies is an ongoing challenge, Maguire says. Despite these research roadblocks, advocates remain undaunted, mostly because of the evolution of the AIDS pandemic into a disease now hitting young women'especially those in the patriarchal societies of developing nations'disproportionately hard. 'According to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, for every 15- to 19-year-old boy that is infected, there are five to six girls infected in the same age group,' says Pekka L'hteenm'ki, director of the microbicide program at the Population Council. 'Women are four times more likely to contract HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases than men. These women need more options to protect themselves from getting HIV and other STDs because the current prevention strategies do not work.' Friedland is even more direct in her assessment: 'People are saying, 'We're desperate; we need something.' Even a partially effective microbicide would give them some sort of protection.'

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

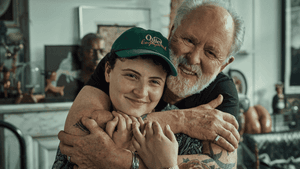

“So much life to live”: Eric Nieves on thriving with HIV

September 03 2025 11:37 AM

The Talk: Beyond the exam room

August 13 2025 3:15 PM

Messenger RNA could be the key to an HIV vaccine — but government cuts pose a threat

August 20 2025 8:02 AM

It’s National PrEP Day! Learn the latest about HIV prevention

October 10 2025 9:00 AM

Amazing People of 2025: Javier Muñoz

October 17 2025 7:35 PM

The lab coat just got queer

August 21 2025 10:00 AM

The Talk: Owning your voice

August 25 2025 8:16 PM

“I am the steward of my ship”: John Gibson rewrites his HIV narrative

September 16 2025 2:56 PM

Plus: Featured Video

Latest Stories

HIV-positive men stage 'Kiss-In' protest at U.S.-Mexico border

December 01 2025 12:56 PM

What the AIDS crisis stole from Black gay men

December 01 2025 6:00 AM

The Talk: Navigating your treatment

August 01 2025 6:02 PM

The Talk: Starting the conversation

July 25 2025 4:47 PM

Thanks to U=U, HIV-positive people can live long, happy, healthy lives

July 25 2025 2:37 PM

How the Black AIDS Institute continues to fill in the gaps

July 25 2025 1:06 PM

“I felt like a butterfly”: Niko Flowers on reclaiming life with HIV

July 23 2025 12:22 PM

Dancer. Healer. Survivor. DéShaun Armbrister is all of the above

July 02 2025 8:23 PM

BREAKING: Supreme Court rules to save free access to preventive care, including PrEP

June 27 2025 10:32 AM

1985: the year the AIDS crisis finally broke through the silence

June 26 2025 11:24 AM

VIDEO: A man living with HIV discusses his journey to fatherhood

June 10 2025 4:58 PM

Trump admin guts $258 million in funding for HIV vaccine research

June 03 2025 3:47 PM

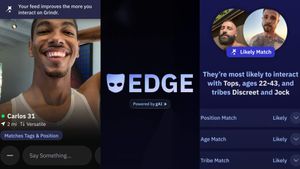

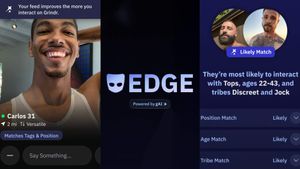

Grindr is reminding us why jockstraps are so sexy and iconic

May 02 2025 5:36 PM

HRC holds 'die-in' to protest Trump health care cuts

April 28 2025 2:11 PM

Two right-wing Supreme Court justices signal they may uphold access to PrEP and more

April 21 2025 4:10 PM

500,000 Children at Risk: PEPFAR Funding Crisis

April 08 2025 3:51 PM