Treatment GuideJust DiagnosedSex & DatingAfrican AmericanStigmaAsk the HIV DocPrEP En EspañolNewsVoicesPrint IssueVideoOut 100

CONTACTCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2025 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

With two different foundations making announcements just a few days apart that they would be awarding multimillion-dollar grants to boost efforts to defeat HIV, the world of research began to look more hopeful and feel more energized, especially when the elusive c word'cure'was actually used. In late June the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation pledged $287 million over the next five years for 16 research teams to study HIV vaccine development. The announcement came on the heels of news that investor Warren Buffett would donate $31 billion of his fortune to the Gates Foundation, thus doubling its current endowment. Less than a week after the Gates Foundation news, the American Foundation for AIDS Research announced a wave of grants for scientists to pursue what many have concluded is the stuff of mere fantasy: a cure for HIV. The $1.5 million divided among 12 research teams may be minute in comparison to the more than quarter billion coming from the Gateses, but Rowena Johnston, amfAR's director of research, says she hopes the grants will catalyze renewed interest in a scientific pursuit that has languished beneath a cloud of embarrassing memories. 'People became very reticent to use the word cure,' she says, recalling the mid 1990s, when scientists made what proved to be faulty claims that triple combination therapy might fully eradicate HIV. 'It's the four-letter word of AIDS research.' During the press conference where the Gates Foundation's efforts were announced, Melinda Gates said a vaccine might take an additional 15 to 25 years to develop, but in the meantime, microbicide research could yield an 'interim hope.' (A foundation spokesperson, however, declined to comment on whether this remark indicated plans for ramped-up microbicide spending.) 'We have all been frustrated by the slow pace of progress in HIV vaccine development,' says Jose Esparza, senior adviser on HIV vaccines for the Gates Foundation, 'yet breakthroughs are achievable if we aggressively pursue scientific leads and work together in new ways.' But according to Mitchell Warren, executive director of the AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition, although the grants will raise the current global spending on vaccine development from $750 million to $800 million per year, that number is still short of the estimated $1 billion to $1.2 billion needed. And amfAR's goals seem no less lofty, considering the track record of treatments. Efforts to eradicate HIV through antiretroviral therapy have been frustrated by the virus's ability to hide from the medications. HIV not only harbors itself in lymph nodes and other 'reservoirs' but cannot be destroyed by antiretrovirals when it is inside a CD4 cell during the latent phase of the immune cell's life cycle. Consequently, much of the amfAR research focuses on these particulars of the virus. 'I think the time is right for this research,' says Steven Deeks, an associate professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and an amfAR grant recipient. 'People are once again talking about eradication.'' The Gates Foundation intends to use its largesse to not just create but better coordinate the search for the elusive vaccine. To date, most research has been conducted by independent groups that usually are using different yardsticks for evaluating their data. The 165 researchers receiving Gates funding have agreed to share their research results with one another. Five of the grants, totaling $92 million, will go toward establishing central facilities at Duke University and the National Institutes of Health, among other institutions, that will assist the members of the research consortium in pooling their findings according to standardized protocol. The remaining 11 research grants are split between two scientific approaches: eliciting neutralizing antibodies against HIV, and creating cellular immunity to the virus. Sandhya Vasan, a member of David Ho's team at the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center, which is researching vaccines that target the immune system's dendritic cells, says the Gates Foundation is taking an active role in controlling the content of the grants in order to ensure that research covers as many bases as possible and is not redundant or ineffective. 'They're different from the NIH, which will just evaluate your idea, and if they say it's good, they'll give you the money and you'll run with it,' Vasan says. 'The Gates Foundation is very much taking a venture capital model where they're going to be very involved.' And amfAR grant recipient Deeks, who will study 'elite controllers''sometimes called 'nonprogressors,' the rare HIVers who are able to control their virus without medications'says the searches for a vaccine and for a cure are actually complementary enterprises. 'Vaccine efforts to completely prevent infection may not be feasible,' he says, 'so efforts at making a vaccine in which complete control occurs subsequent to infection now seems more exciting and feasible.' Vasan adds that such a vaccine could be less than a decade away and could greatly reduce infections, since vaccinated HIVers would have lower viral loads. But even if contributions to vaccine development are the ultimate result of amfAR's research, Johnston doesn't want the world to forget about the 40 million people who are currently infected with HIV. 'My concern is that if and when we have a vaccine one day,' she says, 'people are going to wipe their hands and walk away and figure that their work is now done. But what are we going to do for people who are positive? We can't abandon those people.'

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

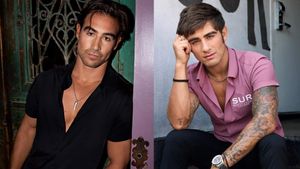

“So much life to live”: Eric Nieves on thriving with HIV

September 03 2025 11:37 AM

Thanks to U=U, HIV-positive people can live long, happy, healthy lives

July 25 2025 2:37 PM

The Talk: Beyond the exam room

August 13 2025 3:15 PM

BREAKING: Supreme Court rules to save free access to preventive care, including PrEP

June 27 2025 10:32 AM

Messenger RNA could be the key to an HIV vaccine — but government cuts pose a threat

August 20 2025 8:02 AM

“I felt like a butterfly”: Niko Flowers on reclaiming life with HIV

July 23 2025 12:22 PM

Dancer. Healer. Survivor. DéShaun Armbrister is all of the above

July 02 2025 8:23 PM

The Talk: Starting the conversation

July 25 2025 4:47 PM

The lab coat just got queer

August 21 2025 10:00 AM

Plus: Featured Video

Latest Stories

HIV-positive men stage 'Kiss-In' protest at U.S.-Mexico border

December 01 2025 12:56 PM

What the AIDS crisis stole from Black gay men

December 01 2025 6:00 AM

Amazing People of 2025: Javier Muñoz

October 17 2025 7:35 PM

It’s National PrEP Day! Learn the latest about HIV prevention

October 10 2025 9:00 AM

“I am the steward of my ship”: John Gibson rewrites his HIV narrative

September 16 2025 2:56 PM

The Talk: Owning your voice

August 25 2025 8:16 PM

The Talk: Navigating your treatment

August 01 2025 6:02 PM

How the Black AIDS Institute continues to fill in the gaps

July 25 2025 1:06 PM

1985: the year the AIDS crisis finally broke through the silence

June 26 2025 11:24 AM

VIDEO: A man living with HIV discusses his journey to fatherhood

June 10 2025 4:58 PM

Trump admin guts $258 million in funding for HIV vaccine research

June 03 2025 3:47 PM

Grindr is reminding us why jockstraps are so sexy and iconic

May 02 2025 5:36 PM

HRC holds 'die-in' to protest Trump health care cuts

April 28 2025 2:11 PM

Two right-wing Supreme Court justices signal they may uphold access to PrEP and more

April 21 2025 4:10 PM

500,000 Children at Risk: PEPFAR Funding Crisis

April 08 2025 3:51 PM

Broadway's best raise over $1 million for LGBTQ+ and HIV causes

April 03 2025 7:15 PM

The Talk Season 5 premieres this spring with HIV guidance for the newly diagnosed

March 26 2025 1:00 PM