Treatment GuideJust DiagnosedSex & DatingAfrican AmericanStigmaAsk the HIV DocPrEP En EspañolNewsVoicesPrint IssueVideoOut 100

CONTACTCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2026 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

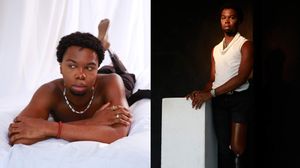

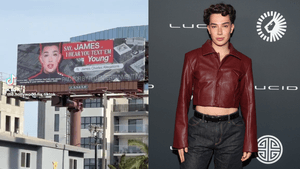

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

At age 19, Marvelyn Brown thought she'd met her Prince Charming. He was sweet, attentive, and hot'so when he asked to have sex one time without a condom, she obliged. Brown worried about getting pregnant, not about getting HIV, but contracting the virus was exactly what happened. 'At that age, I didn't care about HIV,' says Brown, now 26. 'It wasn't an issue of mine. Up until then, my concerns were boys, school, and the prom. HIV was really at the bottom of the totem pole.' Brown is now an AIDS activist, and often speaks about the importance of treatment and testing in New York City and Nashville, the cities where she splits her time. Her story is heartbreaking, yet inspiring. And it's exactly the kind of relatable tale that an expansive media campaign called Greater Than AIDS hopes will encourage African-Americans, a group hit especially hard by HIV, to stay vigilant against the disease. This approach is emblematic of a new kind of campaign, featuring black faces and personal testimonies'on subway cars, on YouTube screens, and even on the fans fluttered by ladies in church, to reduce the stigma and change the perception of HIV. Brown tells her story on the website for Greater Than AIDS (GreaterThan.org), which includes a microsite called Deciding Moments, which contains a dozen personal stories about people and their relationships with HIV, including African-Americans who remain negative, knowledgeable, and empowered. Launched in the late summer of 2009, Greater than AIDS was sparked by a conversation at the 2008 International AIDS Conference in Mexico City between Phill Wilson, the president and CEO of the Black AIDS Institute, and Tina Hoff, the director of entertainment media partnerships at the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonprofit health advocacy group. 'At the time of that AIDS conference, the Centers for Disease Control had just released new statistics on infections in the U.S. that showed that the situation wasn't improving, but was actually worse than we thought it was'with about 40% more infections happening each year' than assumed, Hoff says. 'And when you looked at the epidemic in certain communities, particularly black Americans and men who have sex with men, we were seeing trends indicating we may see a rise in those specific groups.' The hard numbers that Hoff and Wilson saw were indeed disturbing. While African-Americans make up 12% of the U.S. population, they accounted for 51% of all HIV/AIDS cases diagnosed in 2007, according to the CDC figures (the most recent available). The rate of new HIV infections for black men in 2006 was six times higher than for white men and nearly three times that of Latino men. New infection rates for black women, according to the same 2006 numbers, are almost 15 times that of white women and nearly four times that of Latinas. Blacks account for half of the approximately 1.1 million Americans currently living with HIV, according to the Black AIDS Institute. Even with numbers like that, focus groups conducted in mid 2009 by KFF (not affiliated with the Kaiser Permanente health insurance company) and the Black AIDS Institute showed the issue of AIDS was falling off the radar of African-Americans, mostly because it had fallen off the media's radar. 'AIDS the epidemic is out there, but nobody really talks about it,' said a young woman at one of the focus groups. 'That's probably our biggest disease, lack of knowledge,' said another focus group attendant. In response to the findings, KFF, working with guidance from the Black AIDS Institute, created a broad campaign that targeted African-Americans with a goal of keeping the issue front and center in magazines and television, on radio and billboards, and at concerts and sporting events. The hope was that the issue of AIDS would permeate the public's consciousness and lead to discussions and healthy decisions. 'We felt there was really an opportunity for a mobilization that brought together a broad cross section of partners'media and others'to mobilize around AIDS in this country,' Hoff says. The name for the campaign came from a World AIDS Day speech in 2006 by then-senator Barack Obama in which he 'spoke about the power of individuals coming together to achieve something greater, in that case reducing HIV,' Hoff says. 'That really resonated with us.' KFF manages the campaign, which receives additional funds from the Elton John AIDS Foundation, the MAC AIDS Fund, and the Ford Foundation. The CDC and local health departments contribute their resources for local Greater Than AIDS promotions at community centers and clinics. Working with companies like Clear Channel and American Urban Radio Networks, Greater Than AIDS has placed print ads and public service announcements, many featuring the Deciding Moments individuals, in magazines such as Essence, Ebony, Vibe, and this magazine'dozens of radio stations around the country have also broadcast Greater Than AIDS PSAs. Each of the media companies has offered free ad space and time, which allows KFF to direct costs to the physical campaign production, like photo and video shoots. KFF has extended the reach of the campaign by producing programming that's entertaining and informative. For some radio spots, up-and-coming musical artists spoke about their 'deciding moments' when it came to HIV and AIDS. Comedian Steve Harvey hosted a Greater Than AIDS'sponsored radio show that promoted testing and treatment. 'Black media is now more engaged with HIV' due to the campaign, says the Black AIDS Institute's Wilson. Greater Than AIDS also set up booths at the football games of historically black college teams to direct people to HIV information and resources, and it provided testing at the 2009 and 2010 Essence Music Festivals. Also, state and local AIDS organizations in six states and Washington, D.C., approached the campaign to incorporate Greater Than AIDS billboards with local resources and information'that added up to almost 4,000 outdoor advertisements, with Georgia, Louisiana, New Jersey, and Ohio coming on board with promotions in the coming year. The hard question, of course, is whether any of this makes a difference. Are more people getting tested? Are more people using condoms? Are more seeking treatment and sticking to their drug regimens? It's difficult to gauge the benefit of a single campaign, and new infection numbers from the CDC don't come out until this spring. But if Brown had been more aware of HIV at a teenager'if she saw images of people like herself dealing with the issue'she says she would have thought twice about having unprotected sex seven years ago. 'What I like most about [Greater Than AIDS] is how they work to make you relate and how it targets a group disproportionately affected,' she says. When African-Americans don't see their faces or stories, she says, 'You can lose them.' If Greater Than AIDS is a broad campaign that stretches from newsstands to billboards to airwaves, from coast to coast, other efforts are trying a more focused approach. Urban black men who have sex with men and churchgoing African-Americans are being targeted by efforts from the New York'based GMHC. Glossy images of black and Latino couples promising fidelity, respect, and honesty make up GMHC's 'I Love My Boo' campaign, which first appeared in the restrooms of New York's gay bars and nightclubs last year before transitioning to 1,000 New York City subway cars and 150 subway stations. The posters carry the message, 'We're PROUD of who we are and how we LOVE.' Like Greater Than AIDS, the campaign promotes positive self-images and uses its message to encourage responsible behaviors'like monogamy, safe sex, and testing. 'Black and Latino gay men have absolutely no representation of themselves in the media and mainstream society,' says Francisco Roque, GMHC's director of community health. 'Typically, when gay folks are portrayed in the media, they're white gay men. So, for these young men to be on the subway and see an image that looks like them really communicates to folks that you matter, that you're worthy, that people are creating campaigns that speak to you. It changes the conversation and brings people in.' GMHC made sure the posters were of high quality, for reasons deeper than aesthetics. 'We've really made an effort to change the landscape of [HIV-related] materials,' Roque says. 'Previously, materials that targeted people of color were Xeroxed and of poor quality. You didn't really see images of people of color in the gay community that really lifted them up.' In October, GMHC launched another campaign, decidedly different from 'I Love My Boo.' Capitalizing on the prominent role that many pastors' wives play in church culture, the 'First Ladies Care' initiative places the photos of those wives on hand-held fans distributed at Sunday services'with information on testing, safe sex, and the importance of HIV discussion stressed on the back. Brooklyn's First Baptist Church of Crown Heights is the campaign's first congregation, and that church's prominent first lady, Ellen Norman, is its first spokesmodel. Having female role models like Norman encouraging HIV education and discussion is imperative, says Alicia Heath-Toby, director of GMHC's Women's Institute. 'We wanted to empower women of color to engage in discussions around sexuality and prevention and holding women of color very high while doing that,' Heath-Toby says. GMHC is planning to bring the program to other black churches in the city, and it may spread to other areas outside the organization's purview. 'The fans have really caught on,' says Krishna Stone, assistant director of community relations at GMHC. 'People are mailing them to their family and friends who go to churches in other states so their churches will think about launching a campaign'they've gone down south, up north, everywhere. It's very exciting.' Women are targeted in GMHC's 'We're Not Taking This Lying Down' campaign, which features images of women in authoritative poses with messages like 'HIV. Get Tested. Get Control' in newspaper ads, telephone kiosks, and on fliers passed out at community events. A photo exhibit of HIV-positive women of color, launched as an antistigma measure, was featured in various venues throughout New York this fall. Roque says it's important for GMHC and other HIV organizations to remember African-Americans are as varied as any other minority group. 'We realized that all black men don't respond to the same message, so we have to have a variety of things and we have to reach people via their social networks in ways that are really specific to whatever it is they might be into,' Roque says. 'Sometimes we target congregations, sometimes we go after the Ball community, which is another social network, or we work within beauty shops. Sometimes we work within the network of sex parties and reach people with messages that speak to them inside the culture of that social network.' Los Angeles'based AIDS Healthcare Foundation is betting sex will be an effective tool in getting people's attention'the group has a new campaign launching this winter called 'This is Me, Raw,' featuring 14 men, several of color, talking about their experiences with HIV while they take off items of clothing. In the two-minute-long videos, which AHF is considering making part of a national TV and online campaign, all the men end their conversation completely naked'though viewers don't see anything X-rated. The intention is to get people to speak honestly about sex and AIDS, to remind people how intertwined they are, and to show there's nothing about either to be ashamed of. 'Inside this context of being raw, we mean being real, and we intentionally picked up on the double entendre, given the prevalence of barebacking [sex without a condom],' says Whitney Engeran, AHF's public health division director. 'We want to really start a conversation with people about being raw and truthful about HIV.' In the videos, AHF intentionally cast a diverse group of men'white, black, Asian, Latino'betting that the variety of faces will cast a wide net. Instead of launching into these men's sexual orientation or describing their ethnicity, the pieces all begin with the men introducing themselves and saying what they do for a living. 'We wanted to find a common human thread' in the videos, says AHF program manager Bradley Estrin, who came up with the idea for the campaign, which was funded through a grant. AHF works a lot with minority communities in south and east Los Angeles, sending mobile units to those areas to help with testing, along with health and medication information. Engeran says it's important for his organization to know its audience and to respond appropriately. 'If we talk about knowing your status and knowing your health [with people of color] and stay away from some of those things that are hot-button issues in certain cultural contexts'whether it be homosexuality or feelings about masculinity'we're more successful,' he says. '[We'll say] to faith-based communities, 'I'm not here to convince you about biblical tenets, I'm here to talk to you about the health of your parishioners, and that when you know you're positive and on treatment, you're much less likely to spread the virus.' Engeran stresses the point that he hates the term down low, which for him and many others implies black men, specifically, creeping around and spreading sexually transmitted diseases, like HIV. Campaigns like 'Greater Than AIDS,' 'I Love My Boo,' 'This is Me, Raw,' and even 'First Ladies Care' flip the script on down low by presenting a different notion of black sexual identity'one's that informed and honorable and encourages people to lead by example. 'I respond to things that relate to me,' says GMHC's Alicia Heath-Toby. 'So when we couple messages of prevention and anti-stigma with talking honestly about sexuality, and those images look like we do, we're more likely to engage in conversations and behavior in a much more powerful, positive way.'

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

“So much life to live”: Eric Nieves on thriving with HIV

September 03 2025 11:37 AM

It’s National PrEP Day! Learn the latest about HIV prevention

October 10 2025 9:00 AM

Amazing People of 2025: Javier Muñoz

October 17 2025 7:35 PM

The Talk: Owning your voice

August 25 2025 8:16 PM

“I am the steward of my ship”: John Gibson rewrites his HIV narrative

September 16 2025 2:56 PM

Plus: Featured Video

Latest Stories

HIV-positive men stage 'Kiss-In' protest at U.S.-Mexico border

December 01 2025 12:56 PM

What the AIDS crisis stole from Black gay men

December 01 2025 6:00 AM

The lab coat just got queer

August 21 2025 10:00 AM

Messenger RNA could be the key to an HIV vaccine — but government cuts pose a threat

August 20 2025 8:02 AM

The Talk: Beyond the exam room

August 13 2025 3:15 PM

The Talk: Navigating your treatment

August 01 2025 6:02 PM

The Talk: Starting the conversation

July 25 2025 4:47 PM

Thanks to U=U, HIV-positive people can live long, happy, healthy lives

July 25 2025 2:37 PM

How the Black AIDS Institute continues to fill in the gaps

July 25 2025 1:06 PM

“I felt like a butterfly”: Niko Flowers on reclaiming life with HIV

July 23 2025 12:22 PM

Dancer. Healer. Survivor. DéShaun Armbrister is all of the above

July 02 2025 8:23 PM

BREAKING: Supreme Court rules to save free access to preventive care, including PrEP

June 27 2025 10:32 AM

1985: the year the AIDS crisis finally broke through the silence

June 26 2025 11:24 AM

VIDEO: A man living with HIV discusses his journey to fatherhood

June 10 2025 4:58 PM

Trump admin guts $258 million in funding for HIV vaccine research

June 03 2025 3:47 PM

Grindr is reminding us why jockstraps are so sexy and iconic

May 02 2025 5:36 PM