Long-term Survivors

Untitled: How a 3 Year Prognosis Turned Into 30 Years of Art

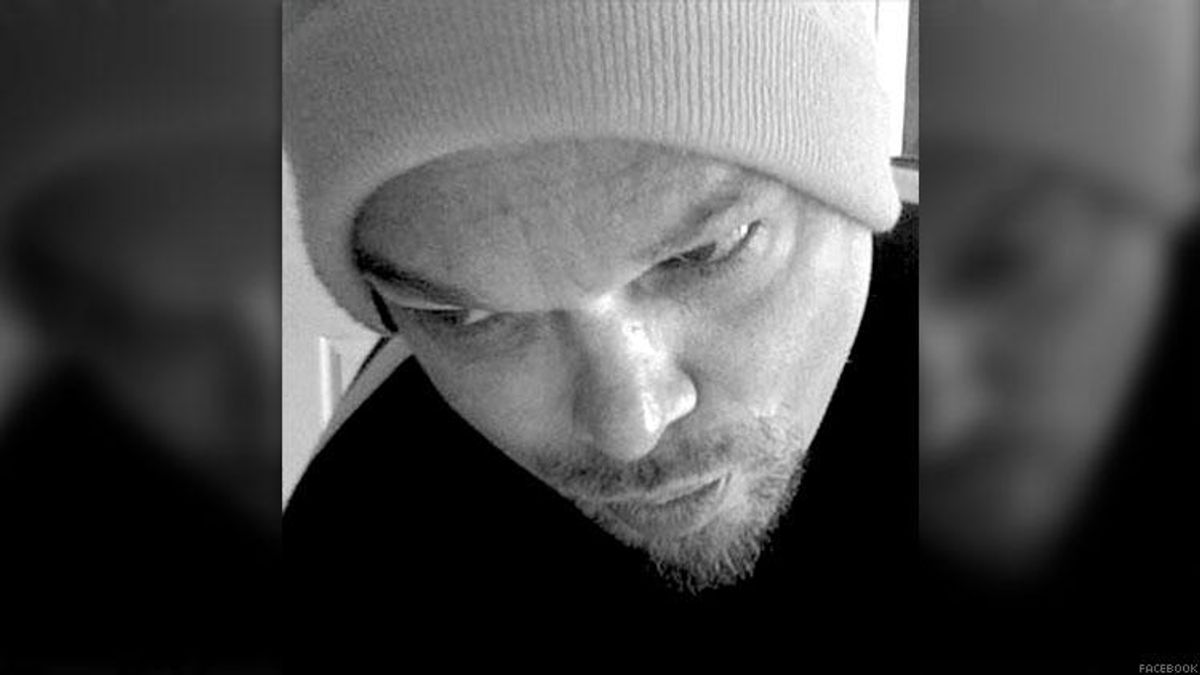

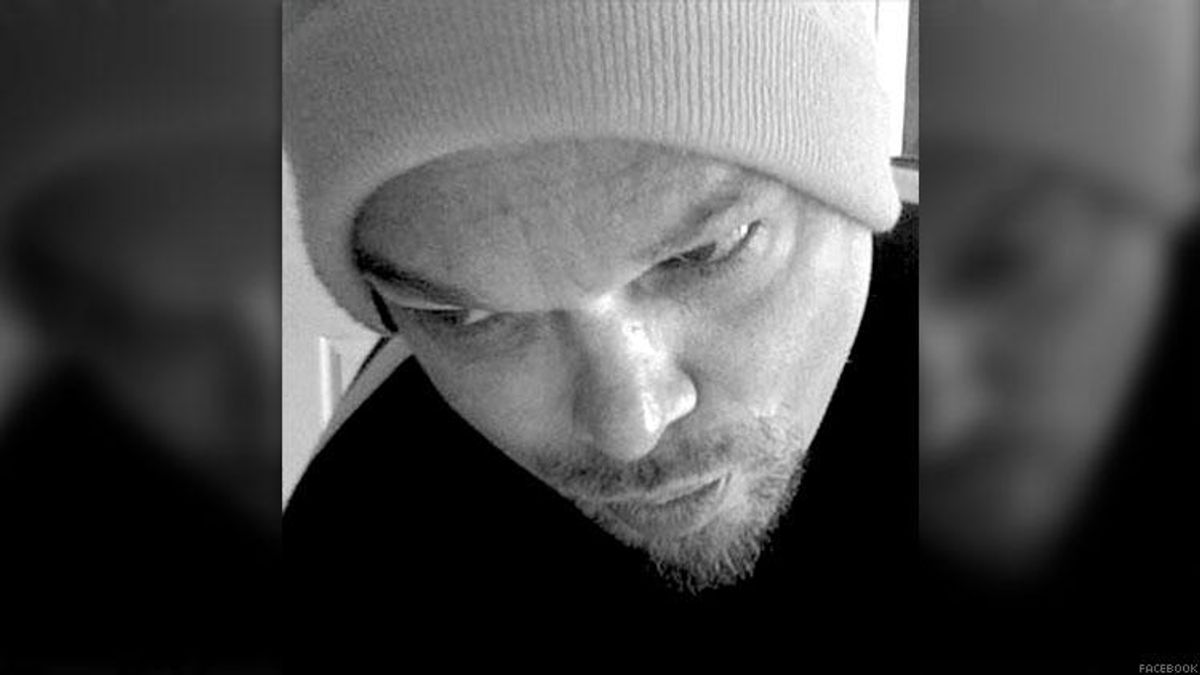

Artist Will Northerner was told by a doctor he had three years to live. Thirty years later, he’s living even bigger.

February 08 2018 6:10 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

Artist Will Northerner was told by a doctor he had three years to live. Thirty years later, he’s living even bigger.

Will Northerner was working as an installation artist at New York City’s legendary Chelsea nightclub, The Limelight, when he learned he was HIV-positive in October 1985, though he suspects he acquired the virus much earlier. “It’s a pity such knowledge can’t be discovered,” he says now about the inability to pinpoint a date.

“After 32 years, I don’t remember a hell of a lot about the doctor who told me, [other] than his nasally voice informing me that I was HIV-positive. He told me that I might expect to live perhaps three more years if I was lucky. I don’t recall much of [my] reaction other than that, with effort, I made myself remain as calm as I could in the face of a deadly viral threat. I doubt if I shed one tear, then or now… out of pity for myself. By 1985, I had already lost count of the people I knew who were infected or dead of AIDS…. In truth, I would have been far more surprised if I wasn’t [positive].”

In the face of that challenge, Northerner established what he calls “my hard, fast, no-bullshit rules for maximizing my quality of living for whatever time I had left.”

The rules included: “Waste absolutely no time — waste no time pretending to like people, places, or things I didn’t like at all;” making no long-term plans; avoiding stress “because stress equals death;” writing and making art every day because “succumbing to fear is not an option;” maintaining a sense of humor and cherishing friends; and a pledge: “if and when quality of life ceases, and torture in being alive begins — I would kill myself.”

The latter obviously never happened — nor did his doctor’s prediction. In fact, Northerner remained remarkably healthy and his T-cells never dropped lower than 700. Thirty-two years later, his T-cell count often hovers around 1000, while “at the same time, my viral load remains undetectable — in short, my greatest surprise is that I am still alive and healthy.”

He credits at least some of that to not being on the early treatments that proved to be incredibly toxic. “I am so fortunate that I never took AZT in the early years of the epidemic,” he says. “I watched far too many of my friends die of apparent toxic levels of AZT.”

Northerner hasn’t had to deal with the kinds of side effects plaguing so many long-term survivors. “I never noticed adverse reactions to any of the HIV-specific regimes I consumed,” and adds, “I have always been so lucky in having doctors that studied the latest breaking viral therapies and thereby prescribed them to me if they proved to be promising.”

However, HIV dramatically impacted Northerner’s mental health. Following his diagnosis, he says he gave up on all long-term plans and “waited for the major symptoms of the deadly disease to set in. Year by year, as my health remained asymptomatic, my friends died. Every month. Every week. Sometimes every day.”

Northerner says he has faced crippling depression over the ensuing years. Although he’s been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, he says the root of his depression wasn’t hard to see: “I survived an obscene number of my closest friends falling ill and dying before my eyes. It was amateurishly simple to deduce a panoply of reasons I might be terribly depressed. Surface reasons on top, but the hideous totality of pictures and vile memories, and the smells, and the tortured moods, and the inescapable tragedy and endless sorrow of watching a whole cadre of old friends — still so awfully young — wither, wilt, and die.... Yes, this got me down, way down — this made me crazy. This made me resort to oceans of self-medication… to survive.”

The ludicrously “positive effect of my experience being HIV-positive, surrounded by a growing ghost list of those displaced by AIDS, was [that] I found myself thinking ‘Holy Shit! What’s next? Ebola? Leprosy? Spontaneous combustion?’”

Today, Northerner is relatively happy and has returned to teaching and making art. For him, it’s important to share his truth, because, “if I made it this long, then anyone can."

Art by William Northerner