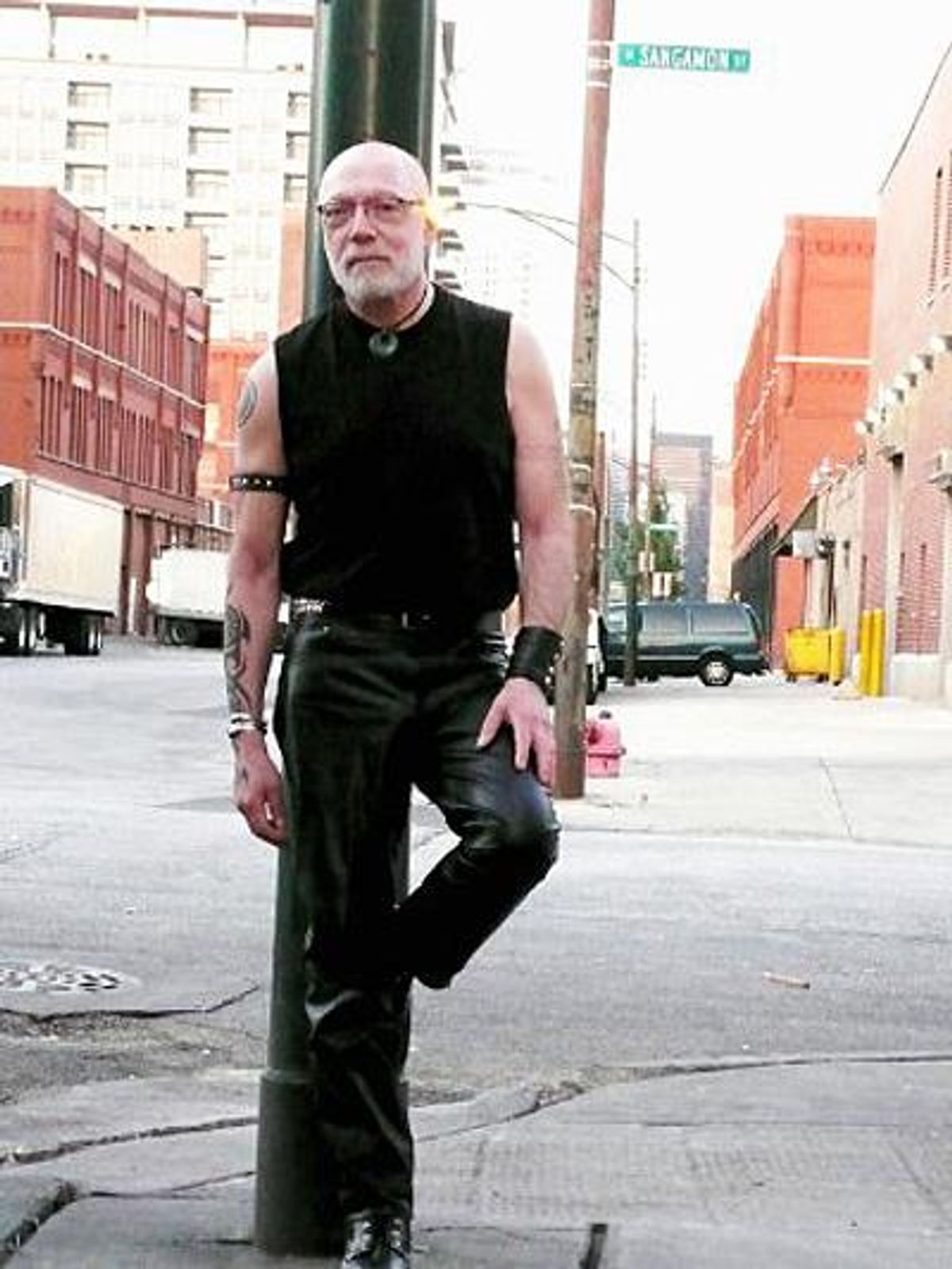

After being pronounced legally dead then waking from an AIDS-induced coma in 1995, Roger Goodman had a new purpose: to create community within queer culture and help others deal with AIDS. Goodman has authored Thoughts of a Tribal Elder: One Queerman's Journey from the Ashes Risen, a memoir of his life living in Chicago and New York City in the '60s and '70s. Having been a part of the Stonewall rebellion, Goodman has been a champion for gay causes for nearly 50 years. He's also fast at work on a new documentary From the Ashes Risen, which he says will shed light on how Chicago's queer community dealt with the AIDS holocaust in the midst of Midwest conservatism. In the film, Goodman speaks to men living with HIV or AIDS today, talking about their lives before and after the emergengce of AIDS in the 1980s.

Your memoir is such a great coming of mind and coming of age story. It was a really inspiring read.

Thank you. It was written in a genuine place. It was written in my reality, there’s nothing made up.

You found out that you were HIV-positive in 1991?

Correct. I’ve probably been positive since the early 1980s or the late 1970s; I didn’t get diagnosed till 1991. My doctor and I figured out that the kind of sex I had till 1983 was perfectly safe sex with no exchange of body fluids. Then I was probably positive when I was living in New York, fucking with 20,000 men. [Laughs] That’s when I got it. Then I was diagnosed with AIDS in 1995.

What was it like when you heard the diagnosis?

Well I didn’t hear the diagnosis until I came out of the coma.

How long were you in the coma for?

Ten days.

You said in the book that you had died and came back to life with a new realization or mission. What was that like?

I entered the hospital with horrible headaches. They were the worst headaches I’ve ever had in my life. I was screaming from the pain and they were putting me on self-infused morphine, where the morphine infuses itself into our body. When my partner walked into the hospital room, my eyes were rolling into the back of my head and I slipped into a coma. They put me in ICU. I was on life support systems and I flat-lined. They were going to turn off the machine, because they figured I was gone. Just before they were about to flip the switch, I opened my eyes and I came back. It wasn’t my time to die. I had too much work to do. And I’ve been doing it and it’s just really wonderful.

Did you have any memories when you woke up?

Yes, I had memories of the death experience. I didn’t have a memory of the coma itself. I asked my psychotherapist at the time who was with me every single day in the hospital while I was in the coma, holding my hand. I asked her where I went and she said, "Oh Roger, you went out to dance among the stars, to learn everything you need to learn, to bring it back to us and teach us."

Wow.

It’s really quite something. She was really a great therapist. But that’s just something for her to say because I was frightened. It was really quite scary to lose 10 days of your life, and when she said I went out to dance among the stars and learn what I needed to learn in order to come back to my community to teach, it was quite amazing. I said that I didn’t remember anything, what was I supposed to teach them? She said, "You don’t need to remember a thing darling. You’re just going to do it with your relationships with people from now on through the rest of your life. You’re going to be teaching..."

You say in your book that all queer people are put on this earth to be teachers. That's a heavy responsibility. What would be your advice to people who haven’t found their courage just yet?

I would say they have to keep working on themselves very hard on who they are as queer people. Not just as human beings, but specifically as queer human beings and to throw themselves into community with other queer people, to surround themselves with people of like mind, like sexual orientation, like asthetic, like spirituality, like history, like politcs. And the more we do that, the more comfortable we are with ourselves and we can take on the role as teachers. I really think that’s why we’re here. We’re here to show people. We could have done this already.

How's that?

During the '80s and '90s, we formed such an extraordinary community of compassion and love and care. We took care of ourselves because no one would take care of us initially, so we formed these service agencies. We became buddies with people with AIDS and we did all this amazing work that was compassionate, spiritual, and highly loving. Had we kept that, we would have been able to become teachers of the world and keep our community – but we lost it. Because HIV/AIDS medications came out, people aren’t dying anymore. So there isn’t a need for a bonded community. There’s just no need for one. I think the primary work right now is to create a bonded community and find it again, so we can look at the world and say Look what we’ve done. We’re desperate people, we’re a factionalized people, but we’ve come together out of respect and love for each other. We can listen to each other with our hearts. We can respect who each other is. We can honor each other’s individuality and each other’s gifts. And we can do this, so let us teach you. That’s our purpose. It’s a very big responsibility. It’s a huge responsibility. But I think it’s a great responsibility.

There were so many deaths in the '80s and '90s that many first generation AIDS survivors often deal with survivor guilt and forms of PTSD. We saw it recently with Spencer Cox who committed suicide a few months ago after speaking about his personal PTSD struggles. Have you had any experience with this?

Yes, a lot. I’ve had a number of psychiatrists and therapists diagnose me with it. I have flashbacks. I flashback to the times I was in the hospital. I flashback to all the funerals and memorial services I’ve facilitated and conducted. I flashback to being in the hospital and holding my brothers in my arms as they took their last breath and telling them It’s okay, you can go. I was just in the hospital and I was terrified because I saw myself going back in again for death, and of course I didn’t die; it was just an infection that needed to be cleared up by an antibiotic. But I flashbacked to that time because it’s what I know. When I get sick, I can’t stay in the reality of that illness, instead I live in the illnesses I once had, that my brothers have had, and all the death that was around me every single day for 12 years. It created PTSD. It was fighting a war. It was no different than being in Iraq. We were fighting battles and we were in the trenches. They were heroes and they were martyrs. It was very difficult. It was war.

What have the therapists offered as a treatment? I would think that this kind of trauma doesn’t pass easily.

No, it doesn’t. It stays with you forever. The thing I do is stay in the moment and not get stuck in the memories, to not get stuck in the powerful feelings of death. I’m so conscious of my mortality. I live with it every day. If everyone in the world lives with the kind of consciousness the people of the first generation of AIDS have, we’d all be dead. We’d be crazy! You can’t walk around thinking you’re going to die all the time...but the people of the first generation of AIDS do it all the time.

You were part of the Stonewall Riots. How far have we come since the times you were marching on the streets in the ‘60s?

I think it’s changed dramatically. I think we have become a culture of assimilation. Wanting to look like everybody else, be like everybody else because we don’t want to scare people: You don’t have to be afraid of us, we’re just like you. We wear your clothing. We have your pets, we have your six figure incomes, we have your gym memberships, we have everything you have. We’re just like you. That’s very different from how it was during Stonewall. We knew we weren’t just like everyone else. We were very different and the culture was a much more cohesive one. Right now, it’s difficult to define a queer culture, because we’ve just assimilated into the larger majority. Fortunately I haven’t, because I can’t. I just can’t.

You say in the book there’s a difference between queer people and gay people. Can you elaborate on that?

I think “gay” is an adjective and “queer” is a noun. Gay is what I do, queer is who I am. Gay has to do with the orientation and the gender that I love. Queer is so much more than that. To me, queer is a complete gestalt. Every minute of my waking life is lived as a queer man. Every spiritual turning that I have is done as a queer man. Every job is done as a queer man. Every relationship is done as a queer man. It’s not just the fact that I sleep with men, it’s so much more. My whole aesthetic is queer. For example, when I go to a concert, I’m aware that I’m sitting in that hall as a queer man listening to this music. I project onto this music what I know about that composer, if he was queer or not, whether he was a survivor of child abuse or not, and I can relate to that composer’s music in an entirely different way than I would have if I just said, “Well I’m gay. That’s how I am so I have to deal with it.” To be queer is to think I’m queer and I love it and I wouldn’t want to be any other way. I have so much more possibility being queer than I have just being a gay man. I have an entire culture available to me if I can only get that culture to come out and become alive. I work hard at that.

Do you think because of the fear of homophobic society, the LGBT community is trying assimilate without being seen as "other" in fear of being discriminated?

Yes. I think we're in a very dangerous time. We’re in a time of radical extremism, and violent homophobia is the order of the day. The radical right really hates us. I know this is going to sound extreme, but I’m convinced that if Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan got into office, they would have opened up the internment camps that were used for the Japanese Americans and start to round up LGBT people. During the AIDS generation, William F. Buckley was calling for tattooing. He wanted to tattoo everyone who was HIV-positive so everyone can know who we were so they wouldn’t have contact with us. They wanted to quarantine us and lock us up in concentration camps. That’s William F. Buckley! He was an enormous force in this country, and he wanted to tattoo us, lock us up. Well I saw that as a possibility with Romney and Ryan as well. They’re so radically homophobic. Dangerously so.

The heart of your book is surviving against such a deeply rooted homophobia. Was it therapeutic to dig deep into all these memories you had to write it?

Yes. It helped me look at myself in very odd, detailed, and spiritual ways that I would not have looked at myself otherwise. The book wrote itself. I was just the vessel. My fingers flew over the keyboard, and the words just poured out of me. It took me nine years to write the book. It was just a matter of writing all these essays as they came to me. I didn’t sit down to consciously write an essay about the eucharistic aspect of sex between two gay men who are HIV positive. I just wrote. I feel like I was a vessel for the universal spirit who had something to say and for some reason I was the person that was chosen to take down the dictation.

You mentioned that when you were living in New York in the ‘70s, you could have had sex with 20,000 men. Today that would be a bit excessive to say the least, but it was a different time back then.

It was completely different.

There’s been recent studies that show bare backing is becoming a trend again. Some think it’s a major factor with the rising HIV statistics. Would men have been less sexually active in the ‘70s had they known more about HIV at the time?

It was a different time. My promiscuity started in Chicago in the '70s. It was a life of bathhouses and backroom bars, picking up men on the streets. When I was living in New York, I could leave my apartment at 1p.m. and be back at 1:15 with another man and have sex with him. I didn’t know that I was passing a virus around, none of us knew. If we knew, I don’t think we’d have been fucking the way we were fucking. It’s very important I think, for people from the first generation to take responsibility for our actions. It’s not that we should feel guilty for infecting other people, because we didn’t know, there’s no guilt trip there at all. But we were using our brothers purely as sex objects and nothing else, as a receptacle for my cock - or me as a receptacle of that man’s cock. That’s all it really was. There was no spiritual connection of any kind. Most of the time, it was just sex with a stranger, and as many strangers as possible. That’s the way we lived. It was the way of life.

You touch on ageism in your book. You say that lesbians don’t segregate themselves from their elders, but gay men do. When was the moment that it started to affect you, personally?

I went through my internalized ageism. I wanted to be 30 forever. Suddenly, I would walk down the streets of Chicago and no one would look at me. Whereas prior to that, every man would look at me as a potential fuck. There was always lust in the eyes of men who would look at me. Then I reached a point where there wasn’t anything like that. I could walk down the street and no one would notice me, I was completely invisible. It’s because I hit 50. That suddenly made me not part of the community anymore. I think it’s a terrible thing. I don’t understand why this doesn’t happen with lesbian women. There’s so many lesbian relationships that are intergenerational, older women lovers with whom they respect their experience and integrity. They want to learn from what that woman has to teach, what it was like for lesbians back in the 1960s or the '70s, and relationships form around that kind of mentoring, teaching, and nurturing. With gay men, that’s not so. We look for beauty and we look for youth. Unfortunately, it keeps us out of really healthy relationships. I’m very fortunate that I found my partner in life at age 65.

Wow

It took me 65 years to find the man that I’m spending the rest of my life with and hes seven years older than I am. He just turned 73 and I turn 67 in two days.

Happy birthday.

Thank you. I wasn’t supposed to live passed 50. There you go! [Laughs]

Drug abuse is a prevalent topic in the gay community. You say in the book, “Being addicted to drugs is a spiritual loneliness that blackens our lives brought on by a lost sense of love in our communities.” What does that mean?

I think something happened when AIDS hit our community. We became afraid of each other. We were afraid that the person we were with was the next possible catalyst for our death. I think we’re still afraid of each other on a certain level. My drug of choice in the ‘70s was cocaine. My drugs of choice in the 2000s was crystal meth, and the thing that crystal meth does is it make all inhibitions leave you. All internalized homophobia leaves, all lack of self-esteem leaves, and all feelings of being unattractive leaves. Relationships don’t get formed, they’re just purely sexual connections that are made thorough the drug. The drug is a real liar. Crystal meth tells you that you are utterly beautiful and that everyone wants you and that everyone near you is utterly beautiful. You think you’re fucking with God. You are so convinced that the man you’re in bed with is the embodiment of the Divine. And that’s not true, it’s just the drug doing its work. But it’s a very dangerous drug because it keeps us out of relationships and it puts us in a black loneliness where we are not connected to anybody in any kind of significant way. The only thing we lived for was the drugs and sex. That was it.

Is that changing at all?

I think that’s changing now. I’m a member of Crystal Meth Anonymous. I’ve been clean for eight and a half years, and I find that the relationships I have with my brothers at CMA are so powerful and healthy and fun loving and joyous and real and compassionate and caring. It’s the kind of community that I saw during the '80s and '90s. Now, it’s still a community of going to the bar and drinking and drugging and dancing and being very carefree and almost saying,“If we get HIV, we get HIV so what? Ill take a couple pills and get on with my life.” And that’s not how it is. It’s a much more powerful community when people say, “I have this difficulty, I have this challenge.” I’m a sex addict and drug addict in recovery. My life is spent with mostly addicts in recovery so we can relate to each other on a deeper level. I don’t think that happens in bars. They’re pure social environments where most men are on Grindr trying to find who they can manage to get together with. That’s not community. Not to my mind it’s not.