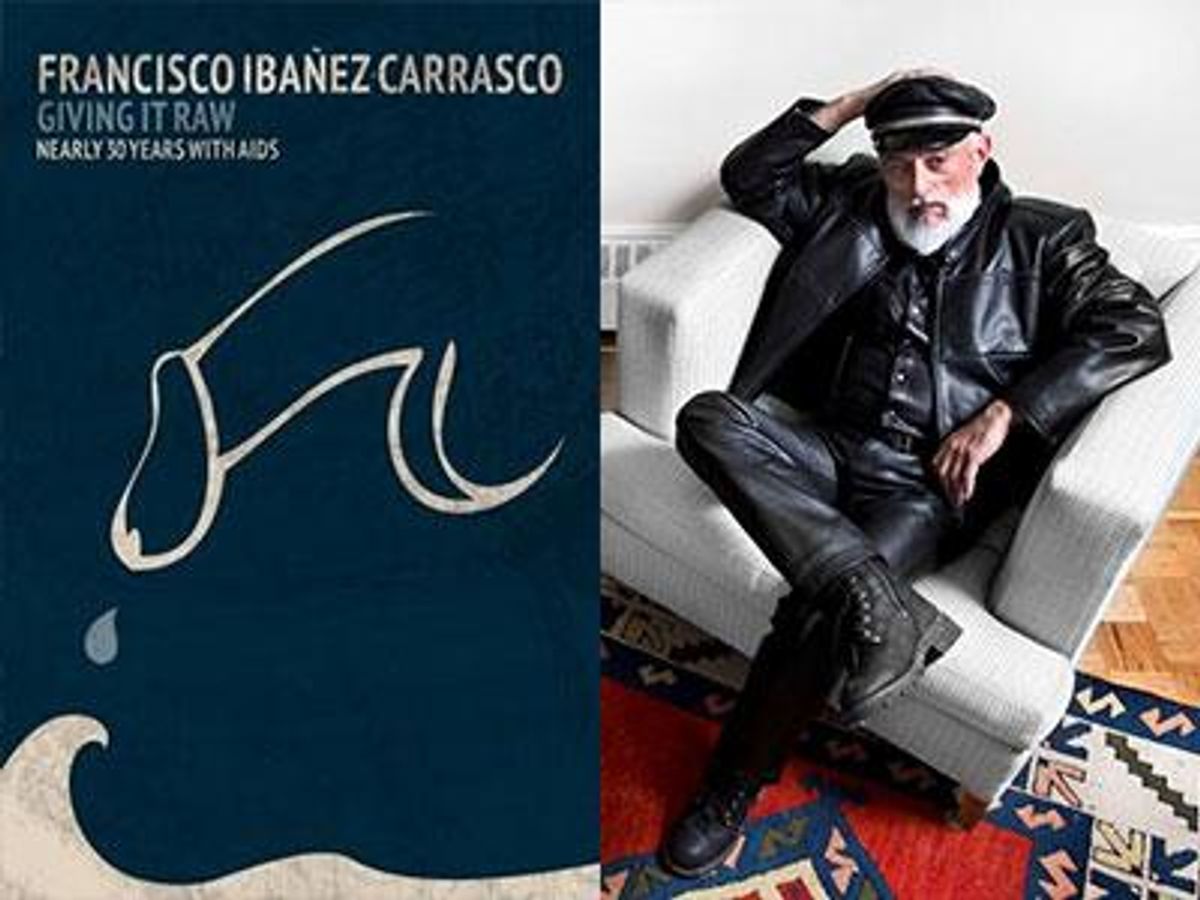

HIV educator and author Francisco Ibáñez-Carrasco's witty, gritty new memoir, Giving It Raw: Nearly 30 Years of AIDS, is, he says, a part of contemporary overshare culture in all the best ways. It has the kinds of "TMI"— too much information — that every reader seeks in a satisfying read: Raw sex, raw sadness, and raw fun.

Visceral and brutally honest, at turns slapstick and erudite, and redolent of sweat, lube, and leather, the book offers the highlights (and lowlights) of the 52-year-old writer's nearly three decades of living with HIV, then AIDS.

A native of Santiago, Chile, Ibáñez-Carrasco immigrated to Canada as a young man, where he received both an institutional education in social science and an in-the-streets-and-bathhouses education on how to live shamelessly as a queer man. Both voices come through in Giving It Raw, his first -- and, he says, most self-searchingly difficult to write -- piece of nonfiction since his novels Flesh Wounds and Purple Flowers (2001) and Killing Me Softly/Morir Amando (2004).

HIV Plus spoke with Ibáñez-Carraso to learn more about the book, now available from Transgress Press.

Giving It Raw's title is as in-your-face and darkly humorous as the writing. How did you develop your unique approach to telling your life's story?

My life has been tragicomic, laugh and tears, and affluence, illness, and wellness. My in-your-face is part defense mechanism and part low tolerance for bullshit. To tell a nobody's memoir, you got to find a firm, proud voice or be swallowed by torrents of media barf…and — trust me — I do have a very ebullient, coy, strategic, filtered, and sexy side to me.

"Nobody" memoir?

In the ever-stretching constellation of autobiographic, memorializing, autopathographic writing, celebrities and victims and heroes reign, but a new type of memoir -- one from the everyday person -- has emerged proudly. Mine is one of them. I might be known in my scientist circle, or maybe even wider, but I am no Bill Clinton talking about AIDS or Greg Louganis or [Sean] Strub or [Michael] Callen, etc. Mine is a nobody's memoir for the everyday person.

So, what will the everyday person gain from reading your not-so-average story?

To learn that we all have the wherewithal, hope, and motives to get up in the morning and live our lives and transform our worlds. Yup, very Miss Universe interview response, I know, but I stand by it.

My memoirs will tell anyone, "You are in this crazy world and you matter!" And, "Get noticed. If one person pays attention, you won't have lived in vain." I also expect a diverse audience to get a rich, if not always expected, understanding of the everyday life of a person living with HIV. The amazing, the horrific, and the quirky.

Amazing? Horrific? Quirky? Go!

Amazing? What humans and gay men do to fight nature, to stretch skin and bones, to stretch the boundaries of relationships.

Horrific? The micro-aggressions we store for each other, the ways in which we mystify HIV and we forget our other ailments and resilience and assets. Online, for example, we ask about HIV only, but we are willing to meet cheating hetero husbands, bulimic gym types, gorgeous bipolar dudes. A micro-aggression is how we are subtly and not-so-subtly unsupportive, and unloving to transgender [men], saying implicitly, "You are not a real man and you will never be."

Quirky? Our queer sensibility mixed with individuality, the way we organize our jack-offs, our sex with others, our open, semi-detached, or monogamous — yeah, right!— relationships. The way we wrap HIV risk in sexy Mylar. Do I get to meet you or is this online foreplay only?

Perhaps we could meet, if only you weren't on tour in Berlin! How is the Giving It Raw world tour going?

I went to London, Berlin, and Istanbul, and conquered. I am so back and working full steam. You can choose between a more detached professional meeting at the HIV program where I work, here at home, or a third neutral space. Coffee on Sunday afternoon?

I wish! Alas, I'm down here in Boston and you're up in Toronto. Speaking of your outreach work, I'm struck, when I read Giving It Raw, by this brash, almost anti-authoritarian stance you have towards living shamelessly with HIV, yet you've also spent your career working within institutions for HIV prevention. What do you make of this tension?

Good question. I work as a scientist and teacher who is connected with organizations, work, and persons I often criticize, but whose help we need very much in order to succeed. They all do good, ethical, and thorough work, if not always prompt and lucid.

However, research is its own convoluted metiér and so are the arts. I am one of the few persons I know who tiptoes in both fields of creativity, methods, and practice. (You see, your question has made my prose prickly right off the bat). I live with the ambivalence and tension between producing data and producing art the same way I live other ambivalence in my life. This is a productive uncertainty and tension because it makes me think everything twice, nothing is easy -- and that is a good way to live.

I'm intrigued -- what else have your life's uncertainties produced?

Living long with HIV creates great uncertainty, but like any other force in life, you ride it or it rides you hard. I am guarded and distrustful due to this uncertainty, but it also makes me hopeful (paradoxically) and ambitious and risky. What do I have to lose?

Yes, I'm uncertain about people, their motives, their egos, but I either crawl into a bad hole or I ride the waves and pangs and spasms of uncertainty.

I think you capture this flux of emotions really well in Giving It Raw. What else do you think readers will get from this book that possibly hasn't been touched on elsewhere in the AIDS memoir genre?

The joy of sex and eroticism that scents everything in our lives -- whatever your medical or body ability is. It is in the way we eat, in our emotional despair, in the urban traffic and spaces.

The fact that HIV is an environmental disaster like global warming and wars, that the band plays on, and we, the people, must ponder and be tactful, but we must also create carnival and drama with it. It is the contradictory stuff of the human condition.

Watch this 1997 experimental AIDS memoir short film, The Body Remembers, made by the author. Ibanez-Carrasco was struggling with Kaposi's Sarcoma and other AIDS-related opportunistic infections at that time and he says drag shows were a way to bring his extended family around him and to create awareness about AIDS.