You think you know what it’s like to die of AIDS complications. You think it’s something that happened in the 1980s and ‘90s, men with purple Kaposi marks and hospital beds vacant as quickly as they were filled. The famous kid dying in that famous Life magazine photo. You think maybe it still happens, to homeless people, drug users, people living in Africa or Asia where antiretrovirals are harder to come by. If you live in America, either you think AIDS is the inevitability of living with HIV (so not true) or it’s been completely eradicated with modern medicine (also not true).

Generally, a lot of the men and women who have HIV now take a single pill a day. They’re healthy and often very fit and attractive. Hell, just look at celebrity trainer Sam Page, model Jack Mackenroth, and blogger Patrick Ingram, all men with bodies and faces ripped from celebrity magazines (the first two even work in/around Hollywood). At 56, diver Greg Louganis—who posed naked for ESPN’s “Body” issue earlier this year—looks better than many of us at 20, and though she’s now public policy wonk, UNAIDS’s Regan Hoffman could still pass for the kind of blond bombshell Tinseltown made famous in the 20st century.

The faces of HIV (clockwise from top left): Sam Page, Greg Louganis, Regan Hoffman, Jack Mackenroth, Rae Lewis Thornton, and Patrick Ingram.

And it’s all true: These are all people with HIV. HIV-positive people can be all that; fit, attractive, healthy, successful people for whom HIV will always be a chronic manageable condition (like asthma or diabetes, both of which can kill without access to medication).

There’s another side to HIV, the one the bigots like to overestimate and and the rest of us underestimate, until it happens to us; or to our celebrities.

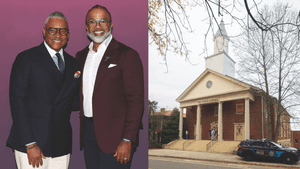

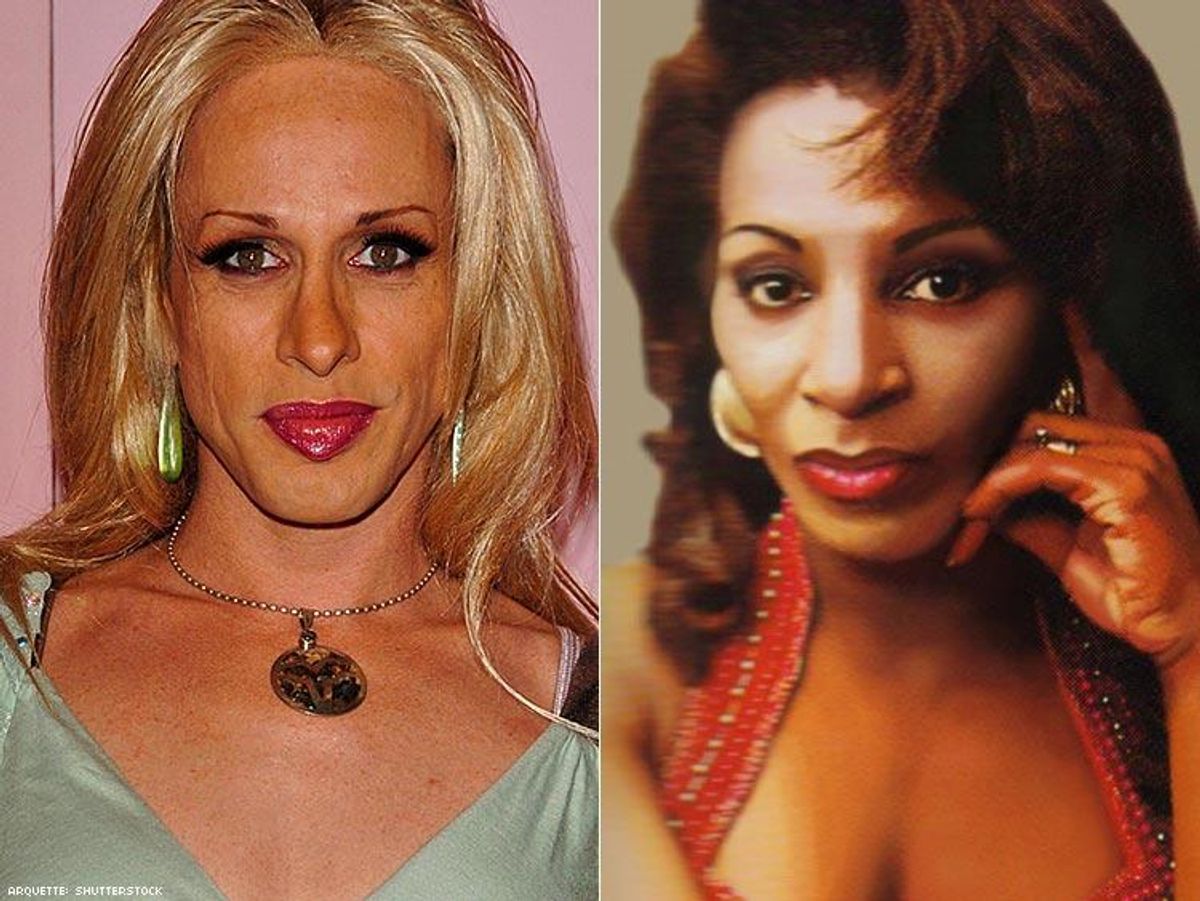

This week has seen the death of two famous transgender women. First was Lady Chablis, the 59-year-old African-American performer made famous by the best-selling book and later Clint Eastwood film Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. Chablis spent much of her life as an elegant and attractive cabaret performer at nightclubs in Savannah, Ga., and Columbia, S.C. Her death from pneumonia did little to diminish her star power which had grown from her role in Midnight (she played herself) to appearances on The Real Housewives of Atlanta and Bizarre Foods America: Savannah. According to The Advocate’s Neal Broverman, she continued her club performances, wrote an autobiography, and “used her fame for good, raising money for diabetes and LGBT causes. She remained beloved in Savannah, even though she lived in South Carolina.”

Lady Chamblis (above) made Savannah a destination

Lady Chamblis (above) made Savannah a destination

In her obituary, pneumonia was listed as the cause of Chablis’s death. Pneumonia, literally an infection in one or both lungs, affects 1 million people a year in the U.S. and kills about 50,000. There’s a vaccine, but it’s usually only recommended for people over 65 or those with immune system issues like HIV.

Pneumonia, just like what Hilary Clinton has, is common and can be caused by bacteria or viruses from things like the flu, whooping cough, and chicken pox. People who have HIV are more susceptible, as are those who smoke, or have diabetes, asthma, or heart disease. When people in the HIV world hear someone died of pneumonia, and they are otherwise in decent health, we can’t help but wonder if it that pneumonia was a complication of their HIV.

Chablis died, at 59, just days before actress-turned-artist Alexis Arquette did so as well.

Arquette, 47 at her death, was the second youngest of a Hollywood dynasty that began with her grandfather Cliff Arquette, a man who dressed as both Mrs. Butterworth (replete with falsetto and mustache) and a character, Charlie Weaver, that became so famous and ubiquitous he occupied the Hollywood Squares in character longer than most other stars of the time. (Cliff, in fact, was rarely seen in public without playing the Charlie Weaver character.)

The family bloodline traces back to Meriwether Lewis (half of for the the 1800s era Lewis and Clark Expedition) for whom Alexis’s own father was named. (He was on The Waltons.)

Arquette’s siblings — Rosanna, Richmond, Patricia, and David Arquette — were reportedly by her side at the end, and supportive throughout her tabloid-ridden life. But if People magazine, ex-boyfriend Robert DuPont, and “anonymous sources” are to be believed, Arquette died of complications from AIDS — an inoperable cancerous tumor and some sort of infection — at Cedars Sinai hospital, as her family played David Bowie's “Starman.” These same “sources” reported that Arquette had been living in a West Hollywood, Calif. Actors Fund home for people with HIV, rather than with her wealthy siblings, out of a need for independence.

Here the thing about all this, and about the attendant reports debating over whether Arquette’s transition a decade ago was still relevant, whether she was misgendered by family members in death or whether she now identified as “gender suspicious” and thus open to pronouns of any sort — the thing here is that nothing about Arquette’s health or death has been confirmed by those closest to her, by her family or by her doctors, and until then we can’t say she had HIV at all. That won't stop the tabloids though, which requires us, too, to comment.

The same can be said for Lady Chablis.

What we do know is that when we hear about transgender women dying in their 40s and 50s, and the cause isn’t violence, we know that complications from AIDS is a very real possibility. That’s because HIV disproportionately impacts transgender women, especially those, like Chablis, who are women of color. We know that the life expectancy for a a black trans woman it’s extremely low and often unlikely to be from old-age natural causes and far more likely to be violence or AIDS complications.

And, those of us in the world of HIV healthcare and activism know that for years, pneumonia and cancer have been code words for AIDS complications. They literally both are AIDS complications (though before headlines start touting that Hilary Clinton is dying of AIDS, we must point out it's one of many potential complications and the majority of folks who get pneumonia each year are statistically HIV-negative).

Most of America, however, still doesn’t even understand what AIDS is, who has it, and how it’s different from HIV so we have to backtrack. Here’s the difference.

HIV has three stages. In stage one, the acute infection stage happens within the first four weeks after HIV infection, and most people will develop what they think is the worst flu ever (think all over pain, sore throat, fever, swollen glands, rashes). Your CD4 count is dropping rapidly. You’re at the highest risk of transmitting HIV to others as well. If you begin antiretrovirals immediately, you may end up like the Jack Mackenroth’s of the world, where you never see another HIV symptom, where you are healthy and happy and look like a TV star on magazine covers, and can literally dance circles around people with other medical conditions. This is often called stage two, the clinical latency stage, where the virus may reproduce at low levels but you may have no symptoms. If you are on antiretroviral medication, you may actually get your viral load (literally the amount of HIV in your blood) to such a low level that it’s undetectable and you can’t transmit HIV to your sexual partners. (Generally, a viral load will be declared “undetectable” if it is under 40-75 copies in a sample of blood.)

For those who are not on antiretroviral medication (often because they don’t realize they have HIV; they simply had a tough flu they got over and didn’t realize that was really the onset of HIV), their viral load is rising and CD4 count is dropping. The HIV in their blood is building up. Some people, those who have problems properly absorbing HIV medications, or who have had HIV a long time and who have already had the effects of severe HIV infection, may also find the same thing happening to them. (There is usually a relationship between viral load and the number of CD4 cells a person with HIV has. Typically, if your viral load is high, your CD4 count will be low—making you more vulnerable to opportunistic infections.)

They will get to HIV stage three. Some medical experts call it HIV stage three, some still call it AIDS.

To be clear, HIV stands for “human immunodeficiency virus,” and it is the virus generally believed to cause AIDS, which stands for “acquired immune deficiency syndrome.” Everyone who has AIDS has HIV, but not everyone with HIV develops AIDS. In HIV stage three, or AIDS, your immune system is shot. Your CD4 cells falls below 200 cells per cubic millimeter of blood (In a healthy person, CD4 counts are usually between 500 and 1,600 cells per cubic millimeter). In this stage, any number of opportunistic infections or illnesses can eventually kill you.

Often people do not know they are HIV-positive until they are in stage three — AIDS — because that’s when their illnesses are so severe they get to the hospital. With treatment, many recover and can eventually get down to even undetectable levels (the space where you still have HIV but the levels in your blood are so low that if you take meds and get proper medical care and good nutrition, there will be little difference between you and those who don’t have HIV, in terms of life quality and expectancy). Most people will never progress to AIDS.

If you do progress to stage three or AIDS, and you do not get treatment, you develop these opportunistic infections and your life expectancy drops to one year. Most people can be saved by drugs.

But let’s reiterate this: nobody dies of HIV. They die of the complications, of which there are many for people with AIDS: such as pneumonia, cancer (lymphoma and Kaposi sarcoma), kidney disease, toxoplasmosis (a parasite you can get from cleaning your cat’s litter box), tuberculosis (mostly in resource shy countries), and about a dozen or more opportunistic infections (things that a lot of people can get but which take advantage of the weakened immune system of people with AIDS and became far worse).

What the tabloids, those anonymous sources and ex-BFs are saying is that Alexis Arquette had stage three HIV, or AIDS, and because of it — and despite the fact that her doctors are at one of the finest and most affluent hospitals in the nation, Cedars Sinai, and her family is imbued with great wealth they were willing to share — despite all that, she had HIV that led to cancer and some unspecified infection, both of which led to her death.

Plus won’t say one way or the other if Arquette or Chablis had HIV, especially not until someone of real authority comes out and says “HIV,” but what we can do as a media outlet and as people who care about people with HIV and AIDS, is to say that we can learn from the deaths of these two trans performers either way. We can learn about HIV stigma that leads away from testing and treatment, about healthcare industries ill-equipped to properly care for transgender people, about governments, pharma companies, and AIDS organizations unwilling to research and understand the differing needs of trans women, instead lumping them in — time and again — with gay men.

In addition to the fact that generally the biology, physiology, and psychology of trans women is different than gay men whether or not they’ve had gender reassignment surgery or not, the reality is that there’s an enormous financial discrepancy between the two groups, which should give anyone pause. In the Treasury Department’s own study released this week, gay married dads have an average pretax income of $275,000, while male same-sex couples without kids have average household earnings of a is $176,000, more than any other group in the country. (Other than the Wachowski sisters and Martine Rothblatt, few trans women can dream of those earnings.)

In fact, transgender people are four times more likely to have a household income of less than $10,000, compared to the general population; 25 percent have lost a job because they were trans; one out of five have been homeless; they are unemployed at twice the rate of the general population; and nearly one in five have been refused medical care. Of course all of these numbers go up if a trans individual is a person of color, like Chablis. (All these stats are according to the famed Injustice at Every Turn report.

Between grotesque and unabated violence aimed at transgender women, particularly those of color, and lack of resources (like housing, proper nutrition, medical care), the average life span of a trans woman of color is 35. Thirty-five. The numbers aren’t all that great for white trans women either.

Given these stats, perhaps we should be asking how Alexis Arquette and Lady Chablis lived so long, but really, two women, two lives spent in the spotlight, careers perhaps not as stellar as they had each dreamed as little girls but both in the Hollywood spotlight turning in performances at points that were widely lauded. These are not lives taken down as part of some drug-fueled True Hollywood Story. These are transgender women who, whether they had HIV or not, were failed by healthcare inequality, by medical establishments that barely know how to take care of them, by access to resources that even in the best of worlds many trans and gender fluid/neutral people do not, that many people of color do not, that many people living with or most at risk for HIV do not.

Shouldn’t their deaths be more than just tragic? Shouldn’t they be a wakeup call?

Because certainly whether Arquette and Chablis each had HIV or not, they both reflect what life is like for people living with HIV who didn’t catch it in time, who didn’t get to undetectable levels, who struggle with treatment or infections or a culmination of many years without realizing what they thought was the flu that one time was really acute HIV infection.

In their deaths, these two women offer up a reminder of healthcare inequities so great even Hollywood couldn't help them.

Lady Chamblis (above) made Savannah a destination

Lady Chamblis (above) made Savannah a destination