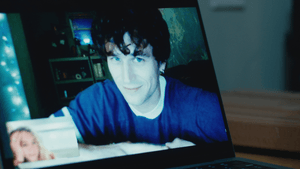

Brooklyn-based film director Matthew Puccini opens his newest short, The Mess He Made, with a close-up—the quick prick of the finger some of us know as the anxiety-inducing Rapid HIV Test. The shot is punctuated by an eerie silence, as a tense Max Jenkins asks, "How long does it usually take?" It’s a question we’ve all asked when getting screened for STDs and HIV—a loaded one, given that catalytic news might be on the receiving end when the waiting period expires.

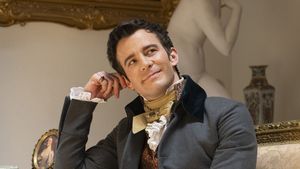

The short film takes place during the 15 minutes the character of Jude waits for his results. Puccini explains, “It’s a very quiet character study of one man that never really goes for the easy emotional punch.” It’s true that Puccini captures the uneasiness that comes from any kind of testing with a softness both visually and through sparse dialogue. It’s also true that Jude is a complex character who, through snippets and allusions to a life outside of the film, does not seem like a man that gets overwhelmed by his emotions.

Set for a world premiere at SXSW this weekend, The Mess He Made, is an exciting contribution to the long standing battle against the stigmatization of HIV in relation to the LGBTQ community, and helps portray those affected by the disease less as promiscuous pariahs and more as human beings able to live a long, healthy life. OUT caught up with Puccini to learn more.

OUT: What was your inspiration for the film?

Matthew Puccini: My producer and I both had HIV scares this past summer and, in supporting him through his and dealing with my own, I realized that it’s something I haven’t really seen portrayed accurately on screen. When I have seen it, it’s shown as a tragic situation, often linked back to the AIDS epidemic. We both felt that there was something so important about showing the screening process in a way that’s detailed and naturalistic, almost mundane, that really shows it in a contemporary light.

You didn’t plan this, but you shot this film right after the election. How did the stakes change for you?

We tried to not let it affect the filmmaking too much. I do think there was some tension in knowing that we were going to be making a film about queer life in a state (Pennsylvania) that had supported an agenda that was publicly against certain rights for the LGBTQ community. If anything, it really fired us up. I love what Max Jenkins wrote to me in an email the morning after the results came in: “Can’t wait to stomp into Scranton looking gay as hell.” I think we all felt like that.

Was reaching out to those who have been tested HIV positive part of your process?

I went to the Gay Men’s Health Crisis to get tested over the summer and went back several times after the fact to speak to the nurses there, who told me about the different reactions they’ve seen from patients hearing good and/or bad news. I think Max’s reaction at the end is an amalgamation of them all, and at the same time very specific to his character and circumstance.

There are some people working very hard in the public eye to change our perception of what it means to be HIV positive. You look at someone like Javier Muñoz, who is currently playing Hamilton on Broadway. He’s HIV positive and very public about it. In the same way that it took people like Ellen coming out for awareness to grow, I think the more we can see HIV positive individuals living their lives in our day to day, the more the stigma around it will dissipate.

false

Where is the stigma for you?

Being HIV positive is still linked very closely to the AIDS crisis. It’s such a recent tragedy and people are still sorting through that, I think. HIV still carries that weight with it, and it’s important to acknowledge the history of where the stigma is coming from, but it’s also important to acknowledge what it can mean now–that it’s something people can live with and test for. There’s a responsibility to educate this new generation, to make them aware of both the same stakes as the older generation and the resources available to them now.

I feel like hook-up apps play a big part in the educational process. Do you think they're a helpful tool?

Apps like Grindr and Scruff are very much a reality in urban gay life and the more those educational tools can be a part of it the better. I’ve personally never had a moment where I felt unsafe, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen to others. People should double-check the facts they’re given and take care of themselves. Ask for proof that your partner was tested recently or is on PrEP. When it comes down to it, one hook-up is never worth a lifelong illness.

What are you hoping for at SXSW?

It’s exciting that this film is going to be seen by a large audience. I would guess that most gay men have probably had an HIV test at some point in their lives, but a majority of Americans probably haven’t. To be able to show what that experience is, hopefully in a way that’s accurate and humanizing, is a huge goal and responsibility for us. After our festival run we’re planning to put the film online, hopefully sometime this summer, and make it available as a resource.

Any plans for a feature film?

We’re still in the early stages of figuring out how this story can be told in a longer form—maybe not this specific one, but something with a similar theme. I want to continue telling stories that grapple with and exorcise gay shame, that explore what it means to be queer and that deal with all the microaggressions and small heartbreaks that take place in our lives. There are so many stories that take place after coming out, and it’s important that those stories have a place, too.