For reasons that may be obvious to many of us disproportionately impacted by the crisis, the dominant images and stories of long-term HIV/AIDS survival are remarkably white, cisgender, male and respectable.

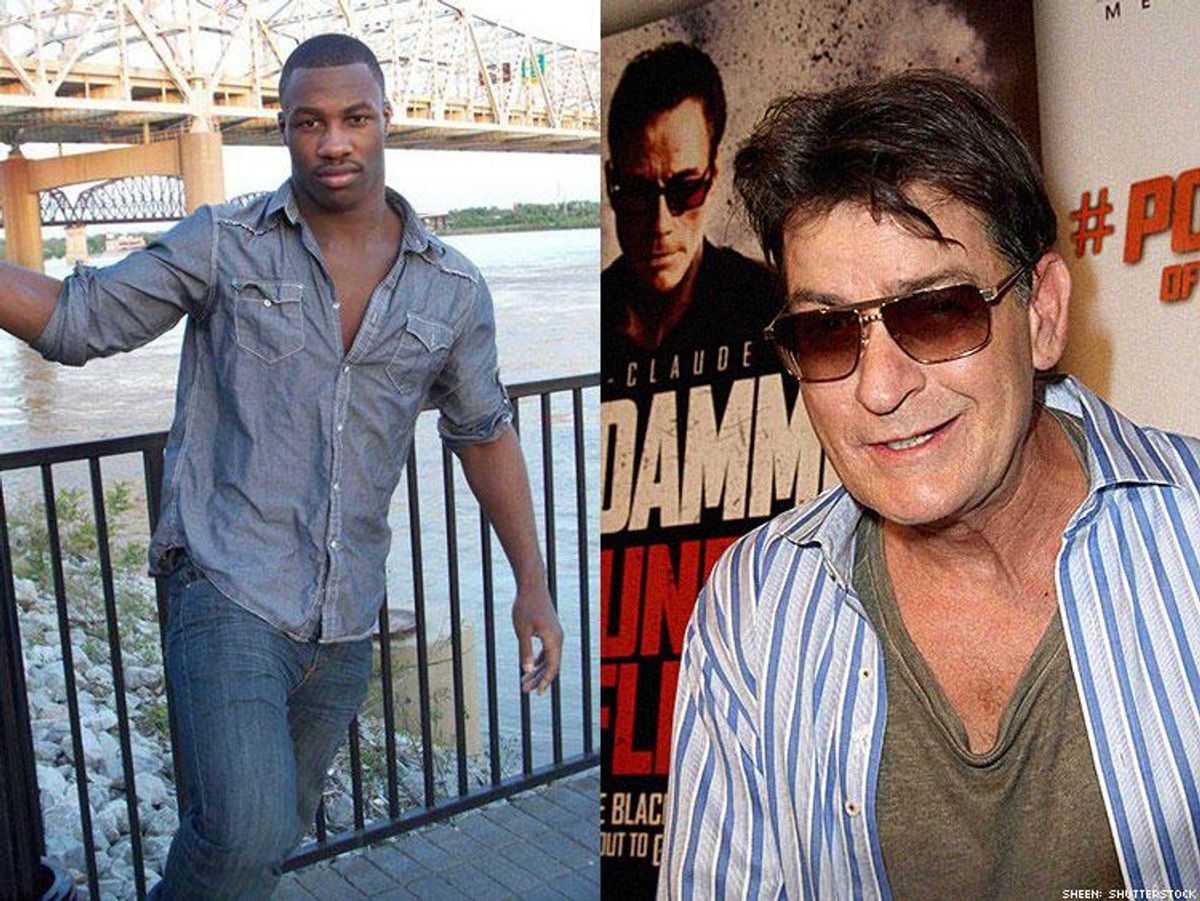

There are a number of reasons why representation doesn’t actually reflect the rest of us. First of all, we know that the access to and quality of healthcare historically – from the dark days of AZT through today’s optimism around PrEP and Genvoya – has largely failed communities of the most marginalized. Thousands from our communities have died, are dying still today after long battles, and their deaths like their lost lives are relegated mostly to statistical analysis of the epidemic. Furthermore, we’ve seen that our Black faces and less respectable narratives are not how the comparably little empathy for our health and human rights fight – at least, nationally - has been garnered over the past thirty years. We’ve seen a monster made of Michael Johnson juxtaposed with an effort to redeem Charlie Sheen who is privileged enough to access a groundbreaking clinical trial. We allowed for too long the shaming of sex workers and drug users, while silently cosigning a perpetual pity party reserved only for the blameless or victimized heteronormative wives and girlfriends of down-low men who have seroconverted. Blame and stigma is only marginally less pervasive and life-threatening than in the 80s, especially when you’re surviving on this side of the color, class, gender and respectability lines.

And yet, as best we can, and against all odds, many of the rest of us are surviving.

With everything about health disparity and treatment inequity being apparent as ever, we still can’t deny that advances in treatment are to be credited for not only what it looks like to survive but who is now surviving longer than at the onset. Whether it’s due to editorial oversight among the health publications and HIV/AIDS historians, or a more intentional editing of our collective story, the task at hand is ensuring diverse faces and narratives are represented in what surviving HIV/AIDS has looked like and will look like. At ten years, and an AIDS diagnosis, into this, having spoken to and worked with so many resilient long-term survivors who look and navigate so much like myself, I recognize that 55-year old white men in the West Village can no longer be the dominant poster children.

If we’re to give the architects and keepers of our AIDS history, mainly white gay cisgender men, the benefit of not questioning whether their construction of our history has been intentionally whitewashed and made in various ways palatable, a shift must still take place. Long-term survival looks more diverse than it ever has and it has always included us, even if those who document the survival of this plague have for whatever reason failed or refused to notice.

It looks like both my current partner and myself, whose bodies remember Atripla and its late-discovered effects (especially on Black men) well enough to take even your latest generation pill and all the glossy page hype around it with a grain of salt. Neither of us is quite forty yet, but my fortieth birthday will mark nearly twenty years of being poz and his will mark fifteen. Long-term survival looks like the South Bronx, like Atlanta, like Anacostia. It’s the ball scene. It’s married and monogamous, with children. It’s the child of the former user, diagnosed at birth, now grown and navigating their own polyamorous life on your sex app of choice.

Right now, arguably more than ever, is the time for more images and stories of long-term survival to mirror the implied hopes and visions in the work of the late Essex Hemphill and Assotto Saint. We can’t continue talking about surviving long-term and ultimately winning this fight without intentionally and consistently showing the most affected that they have indeed survived and can survive this virus which, as the privileged say so casually, is not a death sentence.

We’re tasked with seeing what actually happens when we show and tell as much about the very Black, not cisgender, sex working, addicted or recovering, and impoverished long-term survivors as we do about them needing saving. In fact, such a shift in the representation of survival may help to stave the tide of related death which the Blackest, queerest and deemed least relatable of us have succumbed to in highest numbers. It could be that one of the best ways to increase positive long-term health outcomes among the most marginalized is to show a multitude of living examples of what we actually look like surviving.

Recently, Walgreens rolled out a new ad campaign of HIV survivors that features a 34-year old Black man named Joshua – dressed smartly in a blazer and wearing glasses - with his mother who admittedly had trouble accepting her son’s diagnosis. Though this campaign centers around the usual, respectable or palatable narrative and is predominately white, with Joshua’s story the representation shifts even if only slightly, and our history as depicted thus far begins to take a form truer to life.

AIDS history, like every aspect of American history, is not only inextricably Black but a history of survivors from farthest at the margins. It’s worth counting the inclusion of Joshua’s story as a step in the right direction, but it’s far from enough to alter a revisionist lens that has erased so many HIV/AIDS battles being hard-won.

This article originally appeared on HIVEqual.org