News

Monkeypox Cases are Slowing in the U.S. But it's Unclear if Trend Will Last

New research shows a decrease in the number of new daily MPV cases. But is it enough to stop the outbreak completely?

August 31 2022 5:23 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use.

New research shows a decrease in the number of new daily MPV cases. But is it enough to stop the outbreak completely?

(CNN) -- The pace of new monkeypox cases reported in some major cities -- and in the US overall -- has started to slow recently, but experts say it's too early to know if the trend will last.

On Friday, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky said that she is "cautiously optimistic" about the downward trend, but warned that the overall case count is still growing.

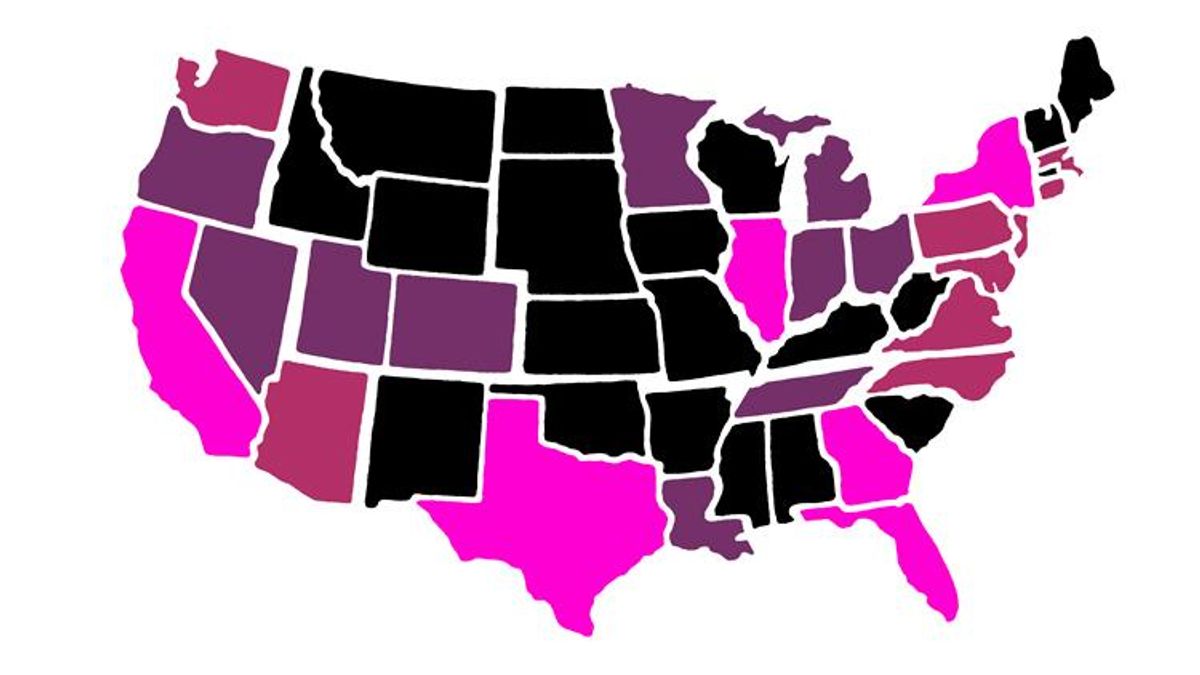

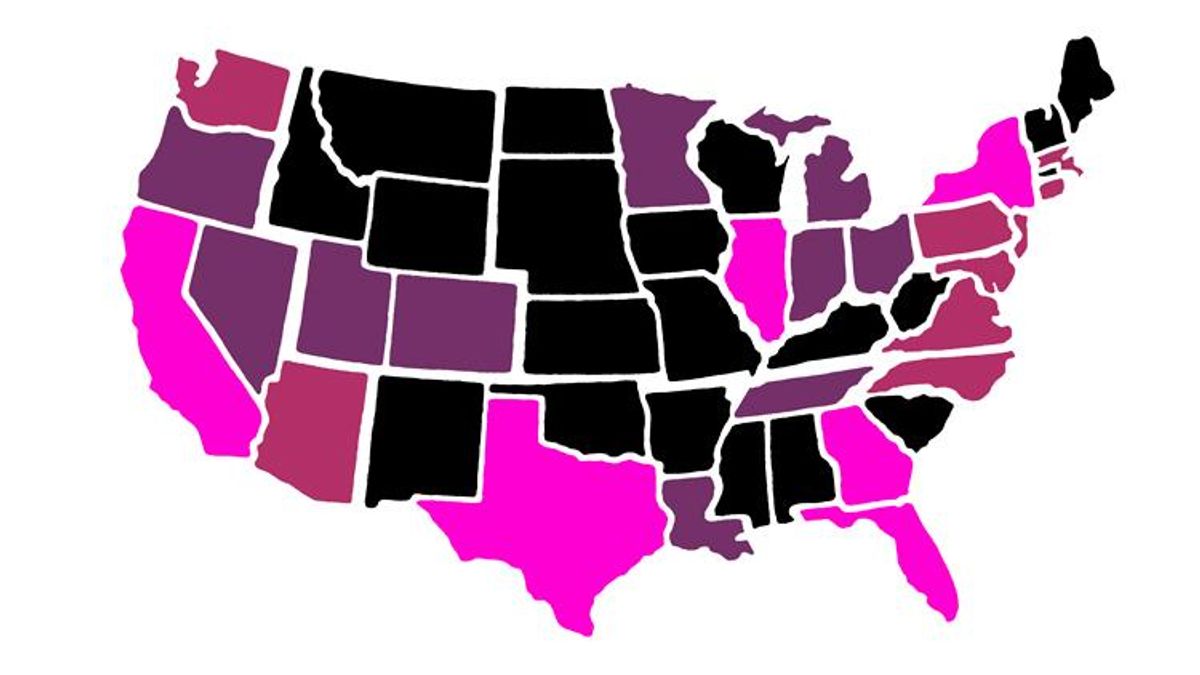

"The rate of rise is lower, but we are still seeing increases and we are of course a very diverse country and things are not even across the country. So, we're watching this with cautious optimism," she said.

Last week, there were an average of 337 new cases of monkeypox reported each day in the US, according to CDC data. That's a 24% drop from two weeks earlier -- a difference of more than 100 cases a day.

A few factors are "working together to bend the curve," Walensky said, including vaccination, behavior changes and harm reduction messages "being heard and implemented."

But many more factors are still in flux, leaving questions unanswered.

Key factors to watch

Local health departments say they are working hard to understand the factors driving case trends.

Washington, DC, has been an epicenter of the outbreak since the beginning; the city has had nearly 12 times more cases per capita than the country overall.

The local health department has seen a "slight decrease" in cases over the past week, but said that "education and vaccines" are two key factors that will drive trends going forward.

And "with 100,000 students that will return to DC within the next week, it is too early to project the trends," they said.

The California health department said that state trends over the last several weeks suggest "stabilizing rather than increasing transmission levels" and daily cases "leveling off."

"The trend could continue but will depend on vaccination and behavior change as noted previously," they said.

New York City Health Commissioner Dr. Ashwin Vasan said last week that the city has also seen "cases begin to fall and transmission slow" in recent days.

Even if cases rise again, Donal Bisanzio, a senior epidemiologist with the nonprofit research group RTI International, predicts that there will be a "rapid reduction" at some point. Monkeypox "is a disease that gives you full protection after you get it," he said. Reinfections aren't a factor.

But no one knows for sure what's next.

"I think every public health response that I have ever worked, we want a crystal ball. It's just exceedingly hard to get there really early on, even for things that we have understood much better for years," said Janet Hamilton, executive director of the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. "Tell me when influenza season is going to end. I can't. "

Outbreak's many moving parts

Experts say that the ongoing outbreak is a rapidly evolving situation, making it difficult to know what to expect in the coming weeks and months.

"There is a very strong interest in using models and thinking about what the trajectories would be in different scenarios," Hamilton told CNN.

All data-driven models require that at least some reasonable assumptions are incorporated. But with monkeypox, the United States is still collecting some of the foundational "shoe leather epidemiology, boots on the ground pieces," Hamilton said. It's a "highly infectious disease that's spreading very rapidly that we don't fully understand."

Some of the stigma attached to the current outbreak may make people reluctant to seek medical attention, discuss recent contacts or come forward to get vaccinated, experts say.

"I'm always concerned about stigma and discrimination, as it can hinder trying to control an outbreak like this," said Dr. Wafaa El-Sadr, a professor of epidemiology at Columbia University who has researched HIV, emerging infections and other diseases.

It could mean people aren't "taking advantage of the important tools we have at hand to stop this outbreak."

Generally, only about 15 to 25% of contacts are being identified, which can skew the understanding of the rate of disease spread, Hamilton said.

"That ends up being a very distinct challenge that then would directly impact what those models look like."

While men who have sex with men have been disproportionately affected in the current outbreak, anyone can get monkeypox and a growing number of cases reported recently have been among women and children -- potentially changing the transmission map even more.

And a recent shift in the federal vaccination strategy -- that potentially expands the existing vaccine supply by as much as five times, but poses other challenges -- marks a major change to another key forecasting factor.

More than 1 million vials of the Jynneos vaccine have been allocated to states and other local jurisdictions, according to data from the US Department of Health and Human Services. However, only about 208,000 doses have been reported to the CDC as administered.

In June, researchers from RTI International published work that estimated the potential burden and duration of the monkeypox outbreak that did not yet have endemic disease. They projected that every three cases could cause 18 secondary cases if no prevention measures were put in place, with outbreaks lasting about six to nine months. Contact tracing and vaccination of close contacts could cut that risk by more than 70%, according to the model.

But new knowledge and information has led them to adjust the model and rerun it, with updated estimates due out in a few weeks.

"We are talking about a model that was done just in the first month of transmission outside Africa. We were thinking that everything was going well," said Bisanzio, who is a co-author of RTI report. The model assumed that the public health response would be quick and effective, especially coming on the heels of the Covid-19 pandemic.

"We know that this story then evolved in a different way," he said, with a lag in response time, hesitancy around vaccination and transmission concentrated within one high-risk community that no one expected. "I can tell you that the numbers (in the updated model) are much higher than the ones that we first estimated."

That said, another one of the biggest adjustments to their model comes from a recent survey of men who have sex with men, in which about half of respondents said they changed their behaviors to protect themselves amid the ongoing outbreak.

The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington built an influential Covid-19 forecast model early on in the pandemic, but will not be doing the same for monkeypox.

"In our mind, this disease is not going to spread into the community as wide as we've seen with Covid," said Ali Mokdad, an epidemiologist and professor of health metrics sciences at IHME.

There are some similarities to HIV that are concerning, but "we don't see that being replicated here," he said, with monkeypox moving out of the body much faster and being much less deadly.

While extensive data-driven models may be largely absent, experts say they are keeping a close watch on trends.

"You don't need a model to tell you that, at this point in time, the strategy has to be to identify those high risk individuals and vaccinate as many as possible," Hamilton said.

For the latest daily numbers of reported MPV cases in the U.S., visit CDC.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox.

The-CNN-Wire

™ & © 2022 Cable News Network, Inc., a Warner Bros. Discovery Company. All rights reserved.