Cleve Jones landed in San Francisco too late for the Summer of Love. Fifty years ago, about 100,000 young people from around the country converged on San Francisco. They were flower children and hippies, queers and artists, radicals and draft dodgers. A generation of freethinkers looked to the city for change, with resistance, liberation, and free expression unfurling in every corner. Because of them, the city gave rise to movements in support of the rights of women, African-Americans, gays, farm workers, Native Americans, animals, and even the planet. Change was everywhere.

A closeted gay teen living in Arizona, Cleve Jones dreamt of this utopia by the bay, where he imagined being welcomed with open arms. But by the time eager peace activist Jones made it to San Francisco, the Summer of Love had long given way to the winter of discontent. The hippies and tourists had gone back to college leaving San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district rife with homelessness, overcrowding, and drug addiction — issues that continued to plague the neighborhood for years to come. Those who remained in the hood staged a mock funeral for the bygone days of the summer of ’67, and urged others to stay home, take up the revolution in their own streets.

But the dream was too powerful and those who felt like outsiders in their own hometowns continued to flock to the city like moths to a flame. Men, women, trans people, folks like singer Sylvester who straddled identity lines before their boundaries had even coalesced — they all came to the city with little more than hopes and dreams.

Roma Guy, a women’s rights activist from Maine, moved there from Africa’s Ivory Coast (a Peace Corps volunteer who met her future wife, Diane, there). Ken Jones (no relation), a black man of both faith and action, served multiple tours in Vietnam, landing in the Castro only to discover just how racially segregated it was. Cecilia Chung showed up in the mid-1980s, an immigrant who battled gender dysphoria and parental estrangement in the city’s Tenderloin, then a hub for street kids, drug users, sex workers, trans folks, and people of color.

ABC’s groundbreaking miniseries When We Rise introduces us to the lives, loves, and struggles of these activists, covering a 40-year span in the long battle for LGBT equality. The last time ABC programmed a series this epic was when Roots was broadcast in 1977. Around 100 million people tuned in, making it a sweeping cultural moment that had a direct impact on race relations in America.

Academy Award-winning screenwriter Dustin Lance Black (Milk) watched Roots in his conservative Texas home, sitting in front of the TV night after night, wide-eyed. “It changed me,” Black says now. “It helped me grow.”

break

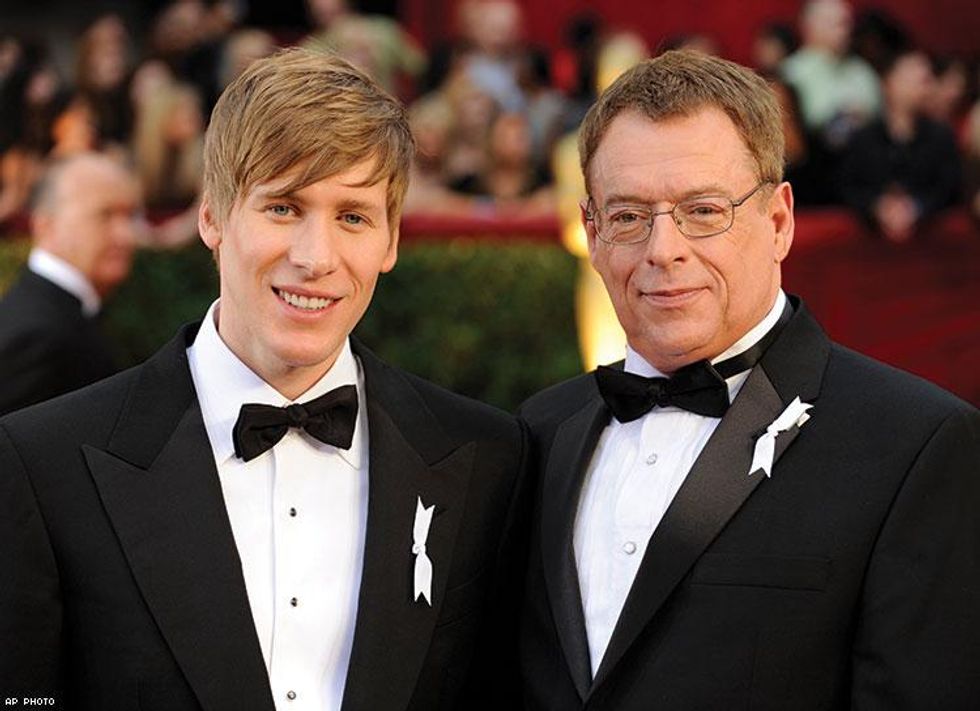

ABOVE: Activist Cleve Jones (right) helped inspire writer, producer, and director Dustin Lance Black (shown together at the 81st Academy Awards).

He’d “never dare to make that comparison because Roots means so much to me,” but while no movement can compare to the struggles our once-enslaved ancestors went through, there’s little doubt When We Rise could have a similar impact on the American conscience.

For those of us who made San Francisco our home during this period, who played roles in this movement, watching We Rise is a stirring emotional journey, a reminder of how strangers became family. It’s also a resounding love letter to a city that was an incubator for social change long before the tech boom and fiscal insecurity began pushing out the same ragtag collection of queers, trans people, and people of color who once made San Francisco what it was.

Having lived in the Bay Area for almost two decades, I know or knew many of the activists, writers, and actors who have helped bring these stories alive. Black helped shepherd the story into being, but he’s not the only director involved. Others helmed one or two episodes in the series, including lesbian filmmaker Dee Rees, gay director Gus Van Sant, and Thomas Schlamme.

How did Black sell ABC on an eight-hour history of LGBT rights?

“There had been several networks over the years who had expressed interest.” in LGBT book adaptations. But Black says he always worried it would take a lot of money and time and the only people who would watch would be LGBT allies. “What use is that?”

This time it was ABC that showed interest. “ABC is a network I was allowed to watch as a kid in Texas, in a Mormon, conservative, military home. And I just thought, if they are truly serious about this, this is finally an opportunity to introduce my LGBT family to my real family. And to tell our stories in a way that I can communicate to my LGBT family but also to my family in the South. I couldn’t pass that opportunity up.”

Above: Rachel Griffiths, Guy Pearce (as Cleve Jones), Mary Louise Parker, and Michael K. Williams as the older activists.

Black dropped everything else to give “all my time and energy to this. It’s been incredibly difficult, but I do think it’s perhaps a once in a generation opportunity to not only tell our stories, but to tell [it] to an audience where it might make a difference.”

Step one was figuring out who to focus on and how their stories could be told so they would intersect organically.

“I wanted it to be people who came from other movements,” he says. “I think it’s very dangerous how myopic the LGBT movement has become and I’m hopeful that we’re coming out of that period. And I wanted to help highlight that by depicting people who came from the black civil rights movement, the women’s movement, the peace movement.”

He was also determined to find people who he could follow throughout the entire timeline of the series, “I wanted it to be people who have been activists their entire lives. Meaning I could start to follow them as youngsters and take them all the way to the present. Well, that’s a really big challenge. And that eliminated a lot of people.”

And Black wanted to make sure that he was depicting — for the most part — people who are still alive. Not an easy feat when the AIDS epidemic took away so many gay and bi men and trans women who were emerging activists. And the filmmaker was determined to break the usual tropes LGBT characters are limited to, like “we’re allowed to be dramatic and serious, but only if we die at the end.”

That doesn’t mean this series is without its share of death and loss. And Ken Jones shoulders a fair amount of it. When Jones served in the Navy, only 5 percent of his fellow recruits were African-American. The sailor was reassigned to San Francisco to spearhead a new training program to facilitate racial integration in the ranks. He began to see that LGBT folks could only gain rights if they joined together.

break

Above: Austin P. McKenzie (as young Cleve, front left) and other youthful activists watch the news in Harvey Milk’s campaign office in When We Rise.

Back then, he says, they had no idea that this was in their future: where marriage equality is the law of the land, tweens identify openly as gender-fluid, and the wholesome Disney-owned ABC network is airing a miniseries about queer and trans lives.

“In all of our visioning, exercising, and our planning, this was nowhere on the radar,” he laughs. “And I tell you, it just breaks my heart that so many of the old gay liberationists are not with us at this moment to witness this. You know, it just makes me very, very sad. They worked so hard, and no one could have imagined ABC doing this.”

Like Cleve Jones, Ken Jones has been HIV-positive since the early days of the AIDS epidemic, when he was taking care of homeless LGBT youth and other people with HIV. He cared for, then buried, his partner, losing his home and all his possessions in the process — not an uncommon experience in a time when gays had few legal protections and two men were rarely on a mortgage or lease together.

“I spent a good deal of time preparing myself to die with dignity and grace,” Jones recalls of that time. “They had initially told me I had about 30 days. So, for about five years I sat there waiting to die. And then slowly this thought kind of dawned on me: Maybe I’m not going to die. So, then I had to go through this whole kind of re-shifting of my life. From preparing to die to starting all over again, and having most of my support network and contacts dead. Starting over again, with absolutely nothing.”

His situation “went from bad to worse” in the early 1990s. After the Rodney King verdict came in, he says, “I actually broke down, and I guess you would say I started experiencing PTSD from Vietnam 25 years later. I didn’t feel comfortable leaving my house. I couldn’t cross the street. If I heard a car coming I would duck and hide underneath another car. I was totally insane.”

Jones connected with PTSD specialists at the Veterans Affairs hospital in San Francisco who helped him through this critical period of his life. As did his faith.

He understands why many young LGBT folks turn away from religion. “It is the church that is unsafe,” he says. “It is religion that is unsafe. But it’s the spirituality and the direct connection to God [that’s important] … that private relationship you have with God. This is such a crucial discussion right now because some people think that God hates gay people. I want to have a very honest conversation because that’s not true.”

Ken Jones experienced the racism that lingered in San Francisco well into the 1990s. As a homeless 20-year-old living out of a VW bus, I recall Ken Jones fighting to develop a home for black, trans, and queer street kids in the Castro. Ironically, the gayborhood worried a shelter would draw the wrong kind of people to the gentrified area.

“And,” Jones recalls, “the biggest opposition came from the people who would love you at 2 a.m. in the morning, and don’t want to have anything to do with you at the crack of dawn.”

But Jones continued to push, insisting that older gays needed to help the queer youth who continued to flock to San Francisco without money, support, or resources — often fleeing hostile or even violent families. All the while, Jones battled racial prejudice within the gay community, while the women fought the sexism. “We had to literally fight in order to participate.”

He says activists in those days “made a mistake. One of our misunderstandings in the beginning was, if there were eight to 10 people at the decision-making table, our thinking was since they’re all gay, white men, two or three are going to have to give up their seat for diversity. Now, they haven’t done anything wrong. They haven’t failed. They’re at the top of their game, they’re doing well, and they’re being asked to give up their seats. How crazy is that? So, some people left with a whole bunch of anger and resentment towards the people coming in taking those seats. Along the way, we realized it’s a lot more healthy if we add more seats to the table, as opposed to asking people to get up and surrender their seat for the sake of diversity.”

Cecilia Chung is one of those who earned a spot at the table, not just as a representative of diversity, but because she gets shit done. When she first came to San Francisco she was estranged from her immigrant family, experienced homelessness, turned to sex work and drug use to survive, and encountered no small amount of violence.

break

“Toward the end, even though I experienced a lot of trauma and violence, I was able to reconcile with my family,” Chung says. “And that really made a big difference in my life. I know I have my family to support me no matter what decision I make. On top of that, my mom actually supported me on my gender reassignment surgery and gave me the funds I needed to fly to Bangkok to have my surgery. It’s hard to describe the joy and gratitude I have. That helped me make that commitment that I really want to do whatever I can to support … others who may be experiencing similar challenges as I did. And to really help them find hope.”

Jones has hope, too, but he recognizes that while things have gotten better, the struggle isn’t over. Racism is alive in our community. “I feel it every single time I’m in the Castro. And I can tell you, I’ve been called a n****r on every street in the Castro, but I’ve also been called a f****t on every street in the Castro.”

He worries about the younger generation. “I think black lives are in trouble right now,” he explains. “And I say that because I meet so many young people who are living their lives with the absence of hope. Can you imagine, not having hope? That the shitty f’d up life you have today is the one you’re going to have tomorrow — and the day after, and the day after. And African-American men have it especially hard, because it’s an hourly occurrence. If you step into an elevator, you see a woman change her purse to another arm. You know that dwells on you; you feel unwelcome. If you cross the street and you hear that ‘tick tick’ sound of doors locking just because you’re crossing the street. It beats you up.”

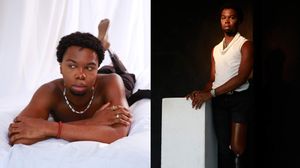

Above: Michael K. Williams and Ivory Aquino, as Ken Jones and Cecilia Chung, offer two of the most moving performances in the ABC miniseries.

Actor Michael K. Williams is one of the famous faces in When We Rise; he’s most recognized for his award-winning turn as Omar, the Robin Hood-style gay criminal on The Wire. Williams, who plays Ken Jones in the series, says the older man has become like a big brother to him.

Having Ken Jones on set, Williams says, “was like having a cheat sheet. I could go right to the source. He’s a very kind and beautiful human being … and he opened his life up to me. These are very painful parts of his life that he probably hasn’t thought about for a long time now. I think it was very hard for him. It’s like he relived it with me again in my performance.”

“I look at his life as someone who is a real American hero,” Williams adds. “This is a man who has been on the front lines for our country. He’s a dark-skinned black man that was in the Navy at a time when it was probably not that easy to get in the Navy. He hid his homosexuality while doing all of that, and then to have all that taken from him ... by the tidal wave and the front lines of HIV and AIDS.”

Williams lost many of his own friends, he says, during the height of the AIDS epidemic. And it’s one reason he felt so strongly about being involved in When We Rise. “It was an honor to tell these stories — I would have done this for free. I have two nephews that are both deceased now. They had complications from AIDS. Michael Frederick Williams, Eric Williams. They were two gay men that I love to death. I felt this was my chance to use the performance as a love letter. To my family first, my two nephews, and to everybody else who suffered from this disease.”

Williams says Jones has fought four battles — for civil rights, for gay rights, against HIV, and in Vietnam. “To have all that history behind his eyes, and to be in that presence it’s really humbling.”

What he calls an “American story of people pulling together and fighting for what they believe in” is a reminder, too, that there’s still work to do.

“We’re expecting an onslaught of backlashes and rolling back of some of our wins we have experienced in the last eight years,” acknowledges Chung. “But I think this TV series shows that we are very resilient. Hopefully people will get the message that we have done this before and, with a little organizing, we can do this again.”

break

Above: Emily Skeggs as young Roma Guy.

Williams agrees. “It’s a good time to tell a story about what people can do when we band together and fight for what we believe in — and at all costs, we don’t give up. No matter what, we don’t give up. It’s been done. It can be done again. We have some history to look back on, to see how things got done.”

That the actors involved in the project can see themselves in their real life counterparts adds depth to the characters. Ivory Aquino will surely be remembered for her role as Chung. But she almost didn’t get the job.

“I told my casting director that I only wanted to cast trans actors and actresses for the trans roles in When We Rise,” Black recalls. When Aquino’s tape came in, Black says, “I watched it and she’s like, a powerhouse, fantastic actress. I called up my casting directors and I said, ‘How dare you send me this tape? I told you to look [only] into actresses who are trans for this role!’ And they said, ‘Here’s Ivory’s number, you should call her.’ And Ivory came out to me as trans on our phone call.”

Playing Chung in When We Rise could be a daunting task for a young stage actress like Aquino. Chung is now a senior strategist at the Transgender Law Center. She was the first openly HIV-positive person and first trans woman to chair the San Francisco Human Rights Commission.

Aquino says the two hit it off. After meeting for dinner in New York, Chung invited the actress to follow her around as she attended a conference. “To have that peek into her life as she’s doing her advocacy work really was very valuable. It really affected me as a person and as a member of the community.”

The two women are now fans of each other, having bonded over their similarities as trans immigrants (Chung from Hong Kong, Aquino from the Philippines).

Chung says, “I feel that I can’t explain to somebody inner thoughts and experiences. But because we have so many similarities it puts me at ease. I think she understands [me].”

While this miniseries is about the movement, the activists, and their work, it’s also about the relationships they build. The on-and-off-again love affair between Roma Guy and Diane Jones (no relation to either Cleve or Ken) — played by actresses Emily Skeggs and Fiona Dourif, respectively — is a bright point in the series.

Above: Rachel Griffiths plays Roma Guy's wife, Diane Jones.

The creator and showrunner says he never thought about taming the sexuality of the characters either.

“People are having sex. Gay people, straight people, bisexual people, you know, trans people. It ought to be depicted in some way or another, particularly when it’s connected to story. This is a story where people are falling in love. And I don’t think there’s anything wrong with the fact that desire is a part of that love. Our young Roma and Jean [played by actress Caitlin Gerard] are the cutest two characters and young actresses in the world. Even as a gay man, I was like, we need to see them go at it. I really am frustrated by mainstream depictions of lesbian relationships; it just seems like the sex has been zapped out of it. And one of the things I learned loud and clear in my research on this is that lesbians seem to really dig having sex.”

The men in the series never tie up their desires, either.

“The great tragedy,” Black says of the time, “is not that people were having sex. The great tragedy was that AIDS happened. And that a government didn’t give a shit. I’m not going to shame a generation of gay men who have been told their whole life that they could not express themselves sexually without being subjected to shock therapy or lobotomy or shame. I’m not going to hide the fact that for the first time they have found liberation and were expressing themselves.”

Just as he wrote Milk for the kid he once was, he created When We Rise for his family “in Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas,” folks who “probably voted for Trump.”

“You want change a mind in that America, you’ve got to start with the heart,” Black says. “That means you better tell a personal story. You better tell an emotional story. You better tell a family story. And you better be damned good at telling a story, because that matters. If you can do that, you might change a heart. You change a heart, you can change a mind. You change a mind, you can start to change a community, and maybe build a bridge between our two Americas. I’m hoping the show uses a language that both Americas will understand.”