At the end of July 2010, a nearly 40-year-old pipeline in Calhoun County, Michigan, ruptured. As crews in the Edmonton, Alberta, operations facility tried for hours to figure what had happened — turning the pipeline off and on three different times — over a million gallons of thick, heavy, toxic tar sands oil was purged from the line. It filled a wet land, then a stream, then contaminated 36 miles of the Kalamazoo River

Two days after the initial reports, I was sent to Marshall, Mich., the site of the rupture to report on the crisis for my employer, the Michigan Messenger. When I first arrived, I went to a bridge, less than a mile from where the creek met the river. I shot video of thick ribbons of oil twirling in the flood stage water. It stunk to high heaven, but I soon found I could no longer smell it as my senses became numb.

It took ten days for the company to admit the oil that was flowing in the river was, in fact, tar sands oil, something it did only because I pointed out to Patrick Daniel, the CEO of Enbridge, the company responsible, that the U.S. Geological Survey maps showed Cold Lake was part of the Alberta Tar Sands deposits.

That spill would become the most expensive inland oil spill in America history (it has cost nearly $1 billion to clean it up, and the company is still working, three and half years later, to remove oil from the bottom of the river). Prior to that admission, the oil was presented as traditional crude oil. Company officials regularly referred to it as “Cold Lake Crude,” named after where it is removed from the earth.

This is not your grandfather’s oil, either. The oil is harvested from the earth with steam injection. It is down there, in solid tar forms, and has to be melted before it can be pumped from the earth. To melt it, companies inject steam deep into the earth, contaminating the water used in the steaming in the process. And when it gets to the surface, it is still thick and filled with sand. It is mixed with a product called diluent, a secret mix of chemicals that may include a toxic dispersant now implicated in health issues from the Gulf of Mexico oil spill in April 2010.

Emergency officials had made health decisions on evacuations based on false information provided by the company. They only evacuated small areas along the river. If they had responded based on the knowledge it was tar sands oil, they would have evacuated 1,000 feet on either side of the river, for the entire length of the spill.

As it became clear that the oil we were dealing with in this disaster was a completely different monster, it also became clear I had been exposed to toxic levels of benzene, xylene and other petroleum-based toxins. Each of them have documented effects on the immune system, causing white blood cell suppression and have been linked to blood cancers as well.

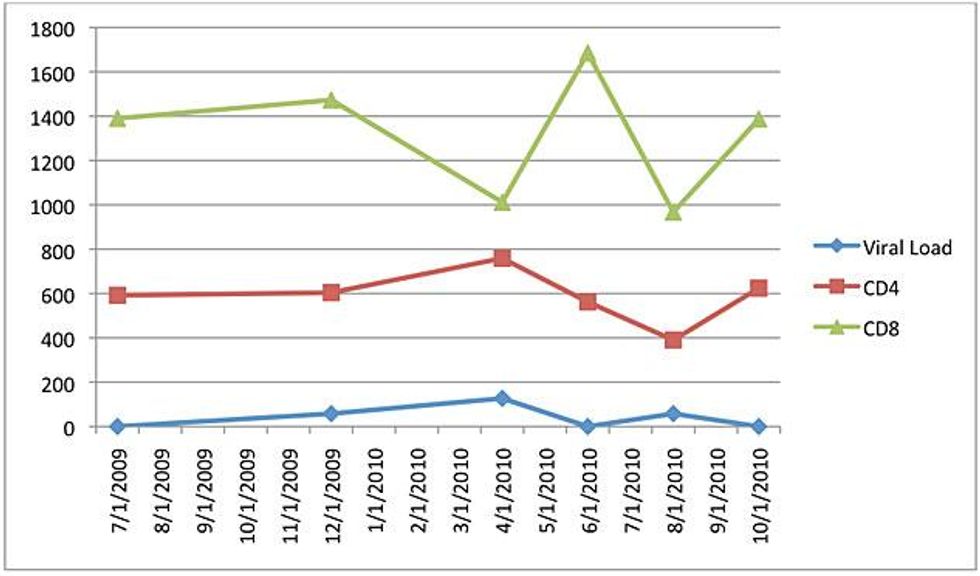

I knew I was in trouble, so I called my infectious disease specialist and requested an immediate blood draw to measure my blood for benzene and evaluate what, if any, impact the exposure may have had on my immune system. The results were revealing. While the benzene was gone from my system, its mark was evident. Just two months after my last lab tests, my CD4s had dropped from 562 to 390. My viral load blipped up, from 0 to 58. Most telling, however, was the corresponding crash in my CD8 measure – from 1685 in to 967 in August. By October, the CD4 had normalized to 624, the CD8 to 1387, and the viral load to undetectable.

A study of the long term impact of an oil spill in Spain, researchers discovered that seven years later, many of the people exposed had developed a dysfunction in certain CD markers necessary for fighting off bacterial infections. I do not, to this day, know if my exposure has resulted in similar abnormalities, but a pulmonologist I consulted late last year for recurring upper respiratory infections caused by bacteria said it was a definite possibility.

Sometime later, I told one of the EPA lead investigators about the lab results. He was visibly shocked by the findings. To this day, it appears that while numerous people have many unexplained health issues that have arisen since the spill and are associated with spill exposure, I am the only person who can document a clear impact on his immune function from the exposure. Health officials never ordered immune function testing for the impacted community. So the impact and tracking of people who suffered exposures may never be fully understood. I am very much a guinea pig on this. A virtual canary in a tar sands disaster arena.

Fast forward to today. The U.S. State Department has been struggling with when — not really if — to approve a massive pipeline project from Canada's tar sands regions in Alberta to Texas. State has to approve the project because it crosses the international border. The project will pump hundreds of thousands of gallons of this toxic substance across Montana, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas.

Keystone officials have been forcibly taking people's land to build the project, and have been promising the line won't be subject to the same risk of rupture the line in southern Michigan had faced.

TransCanada officials (the folks behind the pipeline) promise the Keystone XL pipeline will have a state of the art leak and rupture detection system that will prevent catastrophic line failures (despite there being multiple ruptures on the first leg of the line the first year of its operation). And as the State Department moves closer to approving the longest pipeline in U.S. history, we need to raise concerns about the long term impact of Keystone on those of us living with HIV, in the event of a major failure on the line.

At the end of the day, sending this toxic sludge thousands of miles through pressurized pipelines, combined with the nation's failure in regulating those lines, means we need to do more than watch. We need to demand to know exactly what the company will do when not if, they have a rupture. What are the emergency plans for people with HIV and other immune issues? We cannot afford to be canaries in the tar sands pipeline mess; and our government owes us proof they have thought about and are prepared to address our health in the event of a rupture. And the company needs to do more than issue fluffy PR, and get into the facts about the risks their product poses to our health.

Todd A. Heywood is an award winning investigative journalist from Michigan. His work has appeared in The Advocate, American Independent, HIV Plus magazine, POZ magazine, Michigan Messenger, Between the Lines, Q Notes, and more. His investigative work regularly focuses on the intersection of governmental policy on HIV and the lives of people living with HIV. He runs the independent blog Viral Apartheid, and is currently writing a book about the creation and rise of HIV specific criminal laws in the U.S. He is also a frequent speaker at college and universities. He lives in Lansing with his three beloved dogs Virgil Joshua, Gypsianna Rose, and Lancelot Gobbo. In his free time he enjoys writing fiction, and being involved in theater in a variety of different roles.